Gloria Tamerre Petyarre: True Colours of Utopia

The strength, pride and energy to be found in Gloria Petyarre’s paintings have seen her become one of our most collectable indigenous artists.

Words: Judith White

BIOGRAPHY

Among the many fine Aboriginal artists of the Utopia area, Gloria Petyarre is distinguished by the extent of her artistic development. She is noted for creating vibrant abstract images which are firmly rooted in the natural life of the Australian bush.

Gloria Petyarre was born around 1945 and has spent her life in her native country, Anungara. For many years she lived and worked at Adelaide Bore; for the past few years she has been at Mosquito Bore. As we write she is moving once more within the area. Utopia in the Northern Territory is part of the lands looked after since time immemorial by the Anmatyerre and Alyawerre peoples. It is an area of red earth, of spinifex and mulga, of spiny lizards and hardy marsupials. Gloria and her sisters grew up living a traditional lifestyle and speaking Anmatyerre language, in a big extended family grouping. Among the elders of the group was Emily Kngwarreye, who in her later years would become Australia’s best-known Aboriginal woman artist.

In 1977, when Gloria was a young woman, the Anmatyerre and Alyawerre laid claim to the freehold title of the Utopia Pastoral Lease, ending 50 years of domination by white pastoralists. Two years later, the claim was granted. Since then the local Aboriginal people have made the area a haven for their traditional way of life, moving away from the stations and back into the heart of their country, banning sales of alcohol and lessening their dependence on station stores by reviving the old practices of the hunter-gatherers.

In these conditions their art has flourished, adapting to the new media available to them. By comparison with other schools of central and western desert area Aboriginal art, it is marked by a great freedom of form and a wide range of styles.

The men of Utopia had a reputation for making good shields and fluted boomerangs. But the most striking developments were to come from the women.

Central to the women’s role in caring for the land are their dancing ceremonies, and this practice is at the core of the development of their art. Gloria and her sisters, Ada Bird and Kathleen Petyarre, first practised their art as part of the group of women who painted each other’s bodies in preparation for the ceremonies.

“For most of those women, the time spent decorating and singing and getting ready for the ceremony is far more important than the actual ceremony itself,” says Christopher Hodges, the dealer who has earned Gloria’s trust over some 15 years, holding a series of solo exhibitions of her work at his Sydney gallery, Utopia Art.

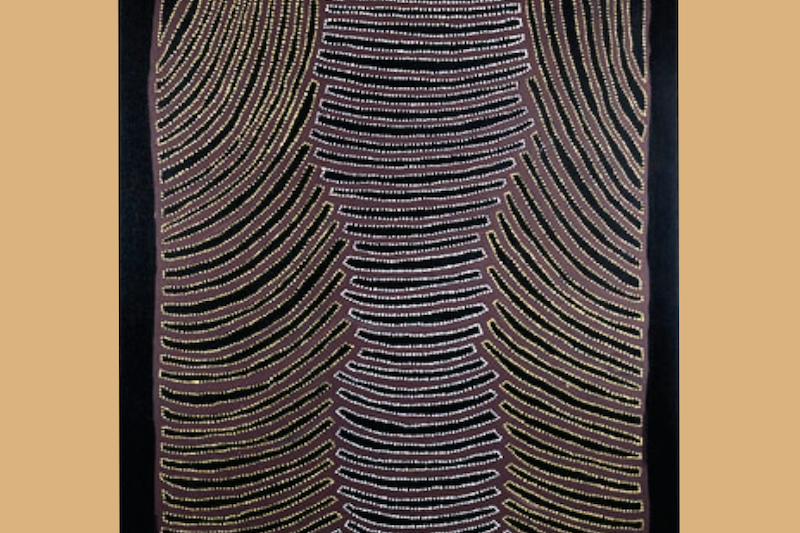

During this period, women’s art in the area has made a rapid transition. At the time they moved back to their own country, the Utopia women embarked on educational programs which introduced woodblock printing, tie-dying and, decisively, batik. The women transferred the ceremonial awelye (women’s designs) from body painting to silk batik, to stunning effect. They used symbols for body painting and for seeds and grasses. From early on, Gloria Petyarre made swirling patterns of these ceremonial symbols. As she began to work in acrylic paint on canvas, these patterns soon came to fill the whole of her pictures.

In works of the 1980s, the viewer can detect the shapes of painted breasts, of ceremonial grounds, round bowls, sticks and animal tracks. Towards the end of the decade, a changeoccurred which can be seen in her 1989 work Awelye (most works are not named by the artist at the time; they acquire names, and the names sometimes duplicate each other). Its bold black and white patterns are moving further towards abstraction; yet then and since, her images have remained close to the life of the earth. She has constantly experimented with line paintings, dots and dashes of colour, always with masterly brushwork.

Growing in confidence, Gloria Petyarre has toured with her work in recent years, to England, Scotland, Ireland, India, Thailand and the United States, always returning to her native ground and to the bush life she shares with her husband, fellow artist Ronnie Price Mpetyane. At the same time her work has continued to mature. During the 1990s she has used colour to create original patterns – of grasses, of hills, and of the patterns on the body of the spiny mountain devil lizard that changes its colours, the creature at the centre of the dreaming of the Utopia peoples.

“Most of the symbolism is quite reductive, quite simple,” says Hodges. “So these little marks become a thing that sets off a series of associations.”

There is a little painting of hers which Hodges owns, and as he speaks of it you realise just how mercurial her images are. “I asked her, what’s this painting? She said, might be awelye, might be little hills, might be rainbows…” It has become known as Rainbows.

A further development came around 1995, with the first of the artist’s Leaves series. She paints them in the most vivid colours – true colours of the bush, but ones many casual observers fail to see – and in patterns which give them movement as though blown by the wind. It was one of this series which won this year’s Wynne Prize at the Art Gallery of New South Wales – a rare achievement for an Aboriginal artist competing with the best of her contemporaries. “Thank you, thank you!” she cried excitedly when Hodges rang from Sydney to tell her she had won.

This has been a big year for Gloria Petyarre, with a touring exhibition of her work organised by Campbelltown City Bicentennial Art Gallery.

Still in her early fifties, she is an artist who continues to develop. The strength, pride and energy of her paintings reflect the life of the land to which she and her people belong. To her, as Campbelltown director Sioux Garside puts it, “the landscape is much more than a national icon, it is a part of her being”.

BEST WORKS, AND WHERE TO FIND THEM

The Campbelltown gallery has an exceptional five-metre long Awelye of 1995, based on the mountain devil lizard. “A visual representation of an immense red landscape,” Sioux Garside calls it. “A strong, rippling canvas, a tribute to the power of the mountain devil lizard ancestor,” says Hodges.

The Art Gallery of New South Wales has several works, including a fine 1994 Awelye (for the Mountain Devil Lizard).

The Wynne winner, still on tour in October 1999 in Newcastle, and in Griffith during November, is entitled Leaves. Consisting of two sets of six panels, each with a different set of tones, it is a good example of Petyarre’s more recent techniques.

The National Gallery, the Queensland Art Gallery and galleries in the Northern Territory all have important works; the Holmes à Court collection also has several, and overseas her work graces the Kansas City Zoo.

PRICE TRENDS

Prices at auction are not a good indication of the value of Petyarre’s work. The highest recorded price to date was paid at Sotheby’s Melbourne auction in the winter of 1998: $3,680 for a 1992 Mountain Devil Awelye.

In fact her prices have grown steadily over the years. “There was a time you could buy a very good piece for a couple of thousand dollars,” says Christopher Hodges. “In the last five years that has easily doubled. And some of the major pieces that sold a few years ago for $10,000 would now have easily doubled.”

But Petyarre paints well across the scale, and there are still little canvases available for prices as low as $750.

WHAT’S AVAILABLE, HOW TO START COLLECTING

Gloria Petyarre is particularly well represented. Her dealers are among the best: Christopher Hodges’s Utopia Art in Sydney, Philip Bacon Gallery in Brisbane.

They advise potential buyers to become thoroughly familiar with the artist’s work, by visiting galleries and reading the literature. The catalogue of the Campbelltown exhibition is a good starting point; and an invaluable refer-ence on the earlier years is Michael Boulter’s 1991 book The Art of Utopia.

Hodges’s advice would hold good for collectors of virtually any artist, but is particularly relevant here. “The mistake a lot of people make,” he says, “is that they follow base instincts, and think they’d better buy it today or someone else will get it. You should look at as much as you can. Most people when they buy a car look in the paper, go to a car yard, look at the opposition. Well, unless you’ve seen 100 pictures by an artist, you haven’t even started.”

Familiarisation with the work of Gloria Tamerre Petyarre may take a little of your time, but your efforts will be rewarded by making some essential discoveries about the relationship of art to the land, and the dynamic development of Aboriginal art. And when you do come to buy, you can be certain that you are acquiring a work by one of the most outstanding Australian artists of her generation.

This article was orginally published in Art Collector issue 10, OCT – DEC, 1999.