What Now?: Cameron Robbins

Some artists use paintbrushes, some use photographic emulsion and others use spray cans. Cameron Robbins uses the wind.

Words: Ashley Crawford

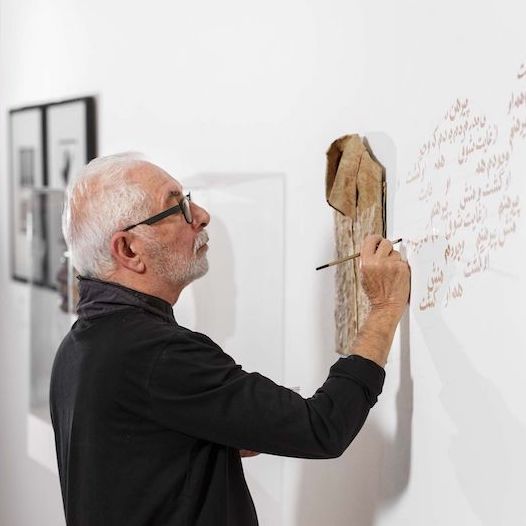

Some artists use paintbrushes, some use photographic emulsion and others use spray cans. Cameron Robbins uses the wind. Robbins is fascinated by nature in all its permutations. I first met the artist in 2003 and even by then his strange, spindly, spinning metal structures were popping up on rooftops and across landscapes around the country. Architects in particular were enamored with his arcane practice, which I had first seen installed on the roof of Daryl Jackson’s architecture firm in Melbourne’s CBD. These weren’t static aesthetic objects, they were machines often designed for drawing and activated purely by the whims of the weather.

Soon after meeting him, I travelled with Robbins on an artists’ journey to the highlands of Victoria’s Falls Creek in 2006. Robbins would arise early and disappear into the mountains to construct odd structures that would get to work for him as he roamed. The results, captured by the thermals, were delicate and poetic and oddly mysterious.

Robbins’ career trajectory began normally enough. He completed his Bachelor of Arts, specialising in sculpture, in 1985. But then, like the breeze, he seemed to drift – always creating and producing, but never quite settling.

That would seem to have changed come 2016. Robbins was curated by Nicole Durling and Olivier Varenne for a major showing at the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in Hobart. Titled Field Lines, it presented the saga of Robbins’ practice, which had over the years grown to include sound and video, photography, installation and sculpture, all still connected to the natural world. Robbins also for the first time committed to a commercial gallery, MARS, in the Melbourne suburb of Windsor, where Field Lines will be reinterpreted this year and where the rooftop already graces one of his manic works.

MONA was an ideal site for Robbins. His work has always referred to the environment in one form or another. MONA’s founder, David Walsh, meanwhile has referred to his museum eventually being subsumed by the waters of Hobart’s River Derwent. Utilising the extremes of humble pencil, high-end hydraulics and the potent power of the tides, Robbins illustrated the inevitability of Walsh’s dire prediction with both technological and aesthetic grace.

“I guess I’m trying to connect to landscape, and to the greater dynamic of the whole climate system; how patterns move through a particular location,” Robbins says. “To me that’s the most direct way to access the greater energies and forces around us.”

Spanning three decades and revealing dramatic shifts in media and approach, Field Lines unveils an artist whose relevance, for better or worse, could not be more timely.

Featured image: Cameron Robbins, Anemograph, Crux, 2015. Giclee or Type-C photograph, on rag paper edition of 5 + 1 AP, printed at 160 x 100cm. Courtesy: the artist and Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), Hobart.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 82, October-December 2017.