A Study in Persistence: Trevor Vickers’ Ongoing Abstract Revolution

From his controversial debut in the landmark 1968 exhibition “The Field” to his latest show at WA Art Collective, Vickers’ six-decade journey reflects the evolution of abstract art in Australia.

Words: Robert Buratti

Few exhibitions have left as deep a mark on the public consciousness as The Field. Launched in 1968 at the newly opened National Gallery of Victoria on St Kilda Road, this groundbreaking show introduced Australia to the bold world of hard-edge, geometric, and colour field abstraction. In a country where landscape and figurative art had long dominated, the exhibition’s presentation of international modernism was nothing short of radical. Curators John Stringer and Brian Finemore had a vision: to present contemporary Australian art that reflected global trends, particularly those emerging from America. Stringer sought to break away from previous exhibition models, typified by exhibitions like Contemporary Australian painting (1957), Recent Australian painting (1961), Australian painting today: a survey of the past ten years (1962), and Australian painters 1964–1966 (1967), which he saw as ‘repetitive and after a few years quite indistinguishable from one another’. Stringer’s ambitious plan was to deliver a series of unique exhibitions presenting Australian art as connected to the zeitgeist of its time, rather than lost in a repetitive cultural vacuum.

Among the 40 artists featured was a young Perth artist Trevor Vickers, then just 25 years old, whose participation would set the stage for a remarkable six-decade journey in abstract painting. Largely self-taught, he credits artists like Mel Ramsden and Peter Booth for teaching him practical skills such as canvas stretching and paint mixing. For Vickers, The Field was a defining moment but not without it’s difficulties. “The backlash was extreme, but it wasn’t coming from anyone who knew anything about painting,” he recalls. “The criticism that ‘this isn’t art’ persisted for years.”

Alan McCulloch writing for Melbourne’s Herald newspaper, accused the National Gallery of Victoria of ‘creating artificial standards of value’, and condemned the curators for fostering ‘a new kind of hazard to national creativity’. McCulloch argued that the art did not reflect any ‘aspect of the Australian environment’, that the artists were ‘gambling on the staying power of current international art fashions’ and simply did not exude enough ‘blood, sweat and tears’ in their work to be recognised as serious artists.

Laurie Thomas at The Australian, admonished the artists for the removal of subject matter, writing ‘the Americans and their faithful followers have left us, and themselves, with something nice and cool like a logical deduction; but only occasionally anything resembling a work of art’.

James Gleeson, no stranger to international influence suggested that upon first inspection the works could ‘give great pleasure and delight’ and ‘have a very superior – and often quite original – sense of design’ but took issue with the imposing scale of many of the works, stating ‘in the long run, the authority which emanates from size alone is a fleeting and fictitious one’. Unlike many of his peers, Gleeson also saw that there was a need for ‘a new starting point in Australian art’, and acknowledged that new attitudes in art have always been met with healthy scepticism, and that ‘the swinging pendulum has become as constant and predictable as a metronome’. He argued that in the past decade alone, ‘the pendulum swung away from the subjective, emotional, violent, accidental and esoteric forms of abstract expressionism to pop art’ and that ‘in the mid-Sixties the pendulum has swung again – this time to the cool, cerebral, refined, controlled and esoteric forms which we try to define with such terms as post-painterly, hard-edged, op or minimal…what has happened to art is quite logical, necessary, inevitable and good … As a form it is just one among dozens that have been thrown up by the ferment of the most rapidly changing times in history. It has a positive and salutary contribution to make’.

Despite the controversy—or perhaps because of it—The Field sparked a national conversation about the nature of art and Australian artistic identity. It challenged viewers to engage with art on a purely visual and emotional level, free from representational constraints. Vickers remembers, “These weren’t paintings made for the future, they were made of the time.” Despite its negative reception, the consequence of the exhibition was that it heralded what Gleeson called ‘a fresh enterprise’ in Australian art, informing not only how art was created but also how it was shown.

Traditionally, commercial galleries were converted homes or apartments, far from the expansive warehouse-style spaces for which large-scale abstraction was envisaged. Trevor Vickers recalls meeting with gallerists at the time to discuss exhibitions in Melbourne, “It was difficult to even find suitable buildings to exhibit the kind of work we were making.

“Following the Field exhibition, Bruce Pollard, who had Pinocotheca Gallery in St. Kilda, approached Robert Hunter and myself to show in his gallery, which was a lovely old Victorian building, niches in the wall, very nice but small space. We turned him down. He asked “Why don’t you like this gallery?” And I said it’s just not right for the work that we ‘re doing.”

He came around the next morning to the studio and took us over to an old hat factory in Richmond. “Do you think we could do it here?” he asked. It was full of junk, but it had everything we needed. So he sold the other place and set up there.”

Pollard relocated to the old hat factory in Richmond in 1970. In the winter of that year, Vickers joined Peter Booth, Dale Hickey, Robert Hunter and Robert Rooney and others in a group show of large works at Pinocotheca. Similar in sensibility and physical space to a New York SoHo loft, the gallery showed artists interested in post-object, conceptual and other non-traditional art forms. Alongside Legge and Watters in Sydney, it was the only gallery in Australia showing experimental work in the late 1960s and 1970s. Over the following years more than 300 artists showed at Pinocotheca including Rosalie Gascoigne, James Gleeson, Bill Henson, Tim Johnson, and Tony Tuckson. Vickers still remembers that this type of gallery provided the right kind of light to properly show large scale paintings. “The height of the ceiling and the amount of natural light was perfect.” This interplay between light and colour remains a hallmark for the artist.

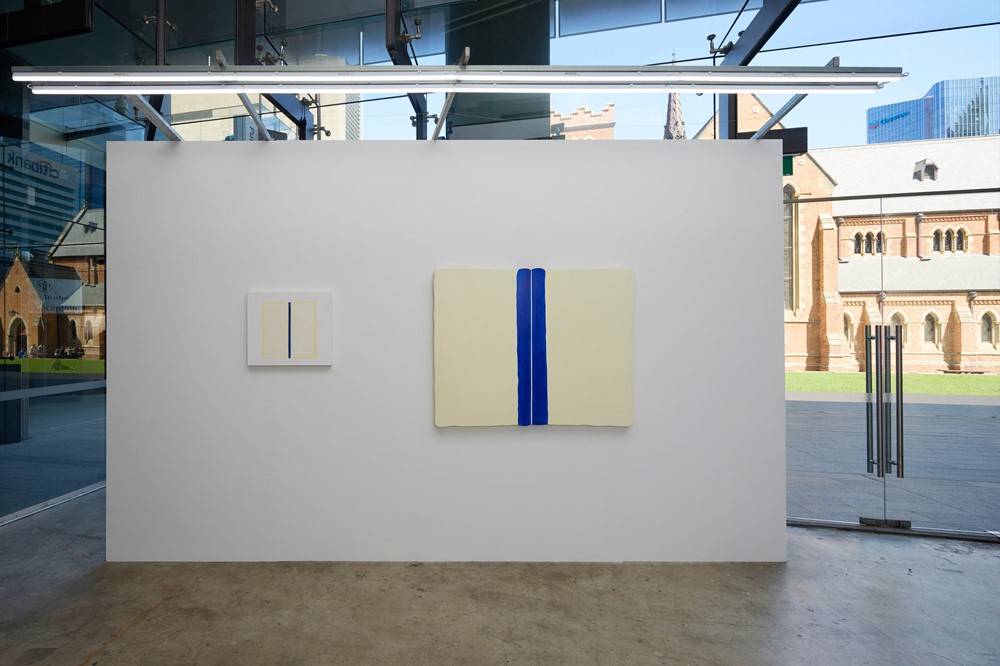

Above: Installation view, Quiet Paintings, Art Collective WA. Image credit Robert Frith, Acorn Photo

After a two-decade stint in Britain, Vickers returned to Australia, settling in Perth in 1995. Now, at 81, Trevor Vickers continues to push the boundaries of chromatic colour field painting. Vickers’ recent work demonstrates a mastery of form and colour that comes from years of dedicated persistence. Remaining grounded in geometric abstraction, his new pieces show a subtle evolution. The hard edges have softened slightly, allowing for a more nuanced interplay between shapes and colours. His sophisticated palette moves beyond primary colours, using muted tones and simplified textures. Alongside these works are a series of what the artist calls ‘quieter works’, some drawn from the early 1970s and never previously exhibited. Characterised by whites, greys, pale blues, and yellows, these works offer a fresh perspective on Vickers’ extensive oeuvre, and a perfect link to his more recent canvases.

From his studio in Fremantle, Western Australia, Vickers’ six-decade career stands as a testament to the power of persistence and evolution in art. His work speaks to contemporary concerns about space, perception, and the maturation of abstract art in Australia—a journey that began with The Field and continues to unfold in the vibrant canvases of artists like Vickers and those that he continues to inspire.

_______________________________________

Trevor Vickers: Quiet Paintings

Art Collective WA

Showing until 26 October 2024

This article was posted 18 October, 2024.

Image: Installation view, Trevor Vickers: Quiet Paintings, WA Art Collective. Images courtesy of the artist and Art Collective WA. Image credit Robert Frith, Acorn Photo