Behind the Scenes: The I in Collective

The first question still asked about an artwork is “Who made it?”. This needs reconsideration.

Words: Ingrid Periz

The recent discovery that Indigenous art from the APY Art Centre Collective may have been helped by white hands has had several consequences, not least a joint State and Federal inquiry into the matter in order to protect what South Australia’s Arts Minister Andrea Michaels called “the integrity of First Nations art.” Questions about the authenticity of APY work also caused the National Gallery of Australia to postpone its First Nations blockbuster, Ngura Pulka—Epic Country, pending its own investigation. And at least one Sydney critic suggested that the shadow cast over the Centre’s work extends to the Wynne Prize, won this year by Zaachariaha Fielding, himself a member of the APY Collective.

Elsewhere in the world, the press has been fretting about the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in contemporary art practice and visual culture more generally. In June, the English science journal Nature announced it would not publish any visual material in which AI was used, again on the basis of what it called “integrity”. All of which prompts a reconsideration of one of the first questions we ask about a work of art: who made it?

In the popular imagination and most art schools, works of art are produced by single, and often singular, individuals, a perception generally reinforced by the market. Even when an artist is known to use assistants or fabricators, the resulting work appears under the artist’s name. Damien Hirst’s dot paintings, almost 1,500 of them to date, are rarely painted by him; every one bears his signature.

Outsourcing the work of making art is hardly new. From the Middle Ages until the late 19th century it was the basis of the European atelier system in which a master artist would work with assistants and apprentices, often training them in the process. Even though many hands might work on a single creation this was not a collective but a hierarchical structure. Like the works of their contemporary avatars – Jeff Koons, Takashi Murakami, Kehinde Wiley, for instance – the results of this labour appeared under one name.

Within Modernism, conceptual and photographic practice have both worked to complicate the question “who made this work?” in large part by refashioning the notion of the work itself. The former, favoring idea over object, helped underwrite practices like Sol LeWitt’s and Lawrence Weiner’s, where others executed the artist’s idea. For these artists “making the work” means conceiving the idea. Warholian and Postmodern appropriation of existing photographs further fractured authorship in ways still being determined by the United States Supreme Court which recently decided a case against Andy Warhol. At issue here, whether Warhol’s formal intervention in using another artist’s photograph was sufficient to be considered work.

Collective artmaking, which answers the question of authorship with “we all made it,” is often driven by questions of politics – ie. power relations, and frequently the power structures of the artworld itself – as much as aesthetics. In 2019, the four artists shortlisted for The Turner Prize turned themselves into a collective in the name of “commonality, multiplicity and solidarity” and won, all sporting stickers supporting Labour candidate Jeremy Corbyn and denouncing “divisiveness.” There is strength in numbers. Ruangrupa, the Indonesian art collective invited to curate last year’s Documenta 15 in Germany, serves as a platform of support of artists, most of whom do not produce conventional art objects. The group’s non-hierarchical and radically distributed method of working effectively unravelled Documenta’s power structure, leading to resignations and a government inquiry.

None of this helps us clarify the APY case, but it does indicate the complexity of authorship within contemporary art where it is widely understood that an artist – and a collective – has authorship of a work regardless of whether it was physically made by them. Indigenous visual practice in Australia found its place within contemporary art in the early 1980s and the position it occupies today is singular within settler societies. To suggest that work from the APY Collective is in some way compromised because it might have been made with the input of others outside the Collective is to deny the Collective’s members true agency. Not only does it fail to understand the complexities of artmaking, it refuses to extend contemporary art’s varied models of authorship to all Indigenous artists. It suggests Indigenous authorship is in need of special protection and in this, it risks paternalism.

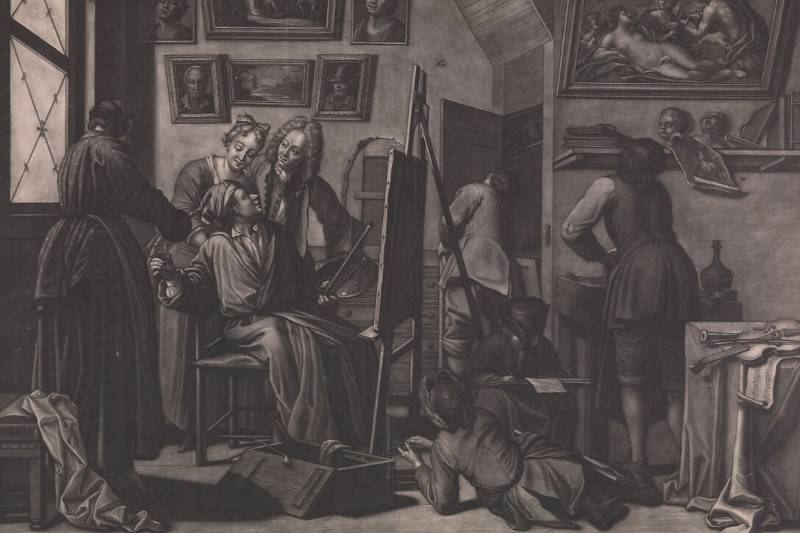

After Jan Josef Horemans the Elder, The Painter, c.1730. Mezzotint, 67 x 50cm. Courtesy: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 105, July to September 2023.