Cultural Capital: For better or worse

What are the obligations of a committed dealer to their artists?

Words: Micheal Do, Andrew Frost, Carrie Miller

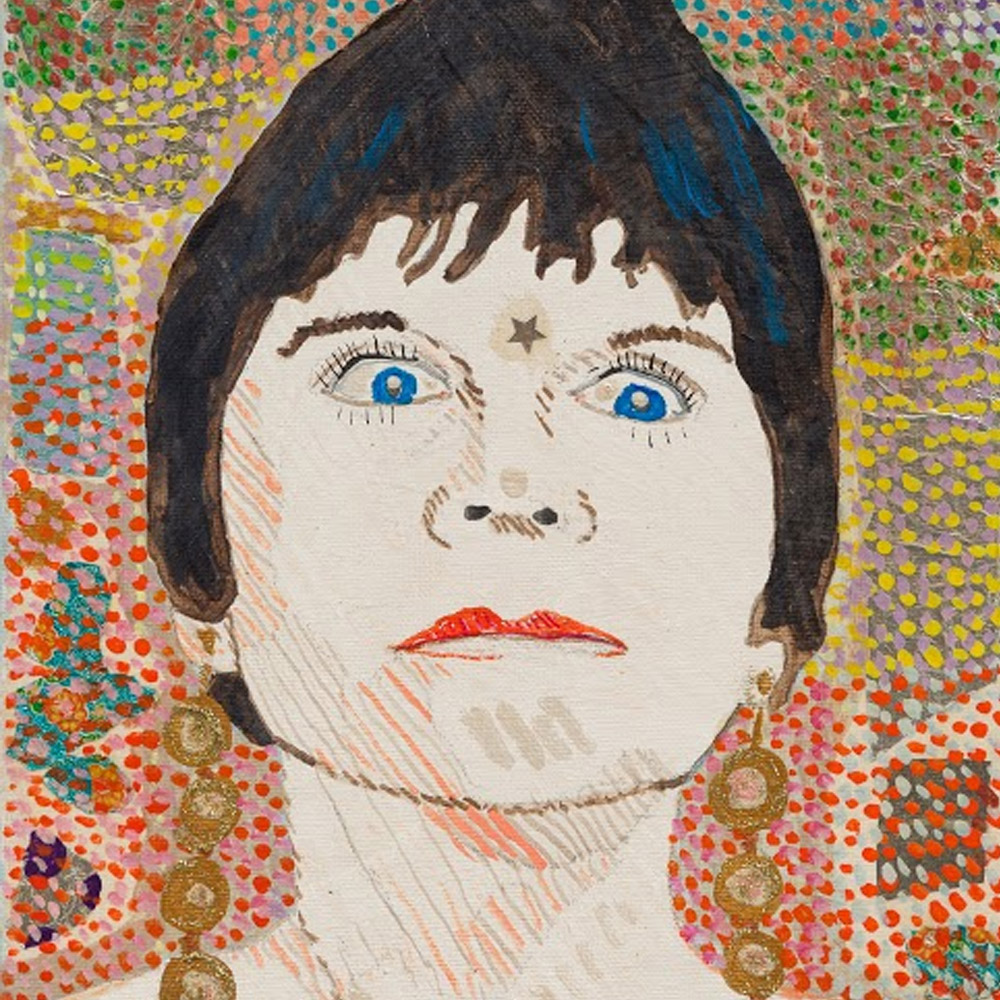

Illustrations: Coen Young

The committed gallerist has historically formed the cornerstone of the art market — providing advice, mentorship and services to artists and collectors. However, the proliferation of art fairs, the rise of savvy auction houses, along with the internet, have rapidly democratised the way art can be consumed, purchased, shared and ultimately collected. More than ever, collectors have greater tools at their disposal — advisers, online forums and social media — to assist them in the evaluation and purchase of art.

Long gone are the days where one had to develop bonds with gallerists and artists to access art (and not to mention, actually visit exhibitions). By the same token, artists have been gifted with a greater freedom to exhibit and commercialise their art, bypassing galleries altogether through direct-to-consumer models like online only galleries or Instagram sales.

As the contemporary art landscape marches towards the impersonal, increasingly privileging different avenues aimed at speeding up the buyer process, it’s timely to ask, what are the obligations of a committed dealer to their artists? And what might the more traditional versions of this relationship offer collectors?

Micheal Do

Exposure

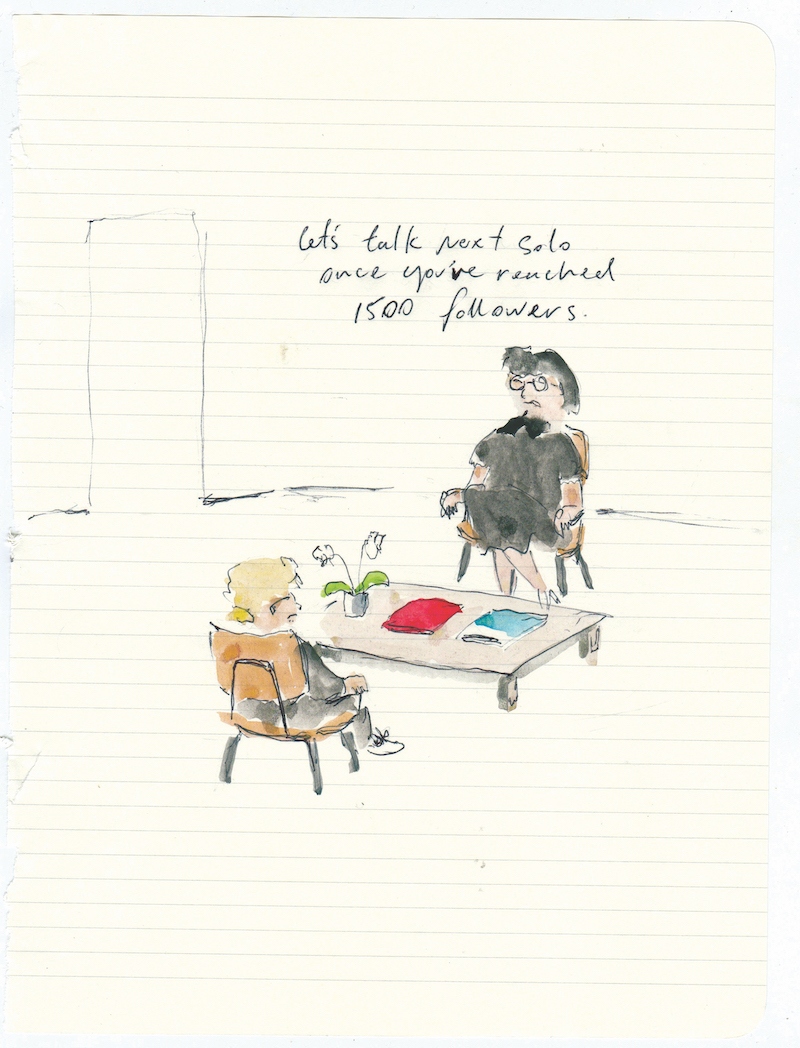

For any artist who signs up with a gallery, the most minimal expectation is a regular show every 18 to 24 months. This is the traditional, historical basis for the artist-gallery relationship, sweetened for the artist by inclusion in gallery group shows, additional sales between shows, and the liaising of professional hook-ups between collectors and the artist.

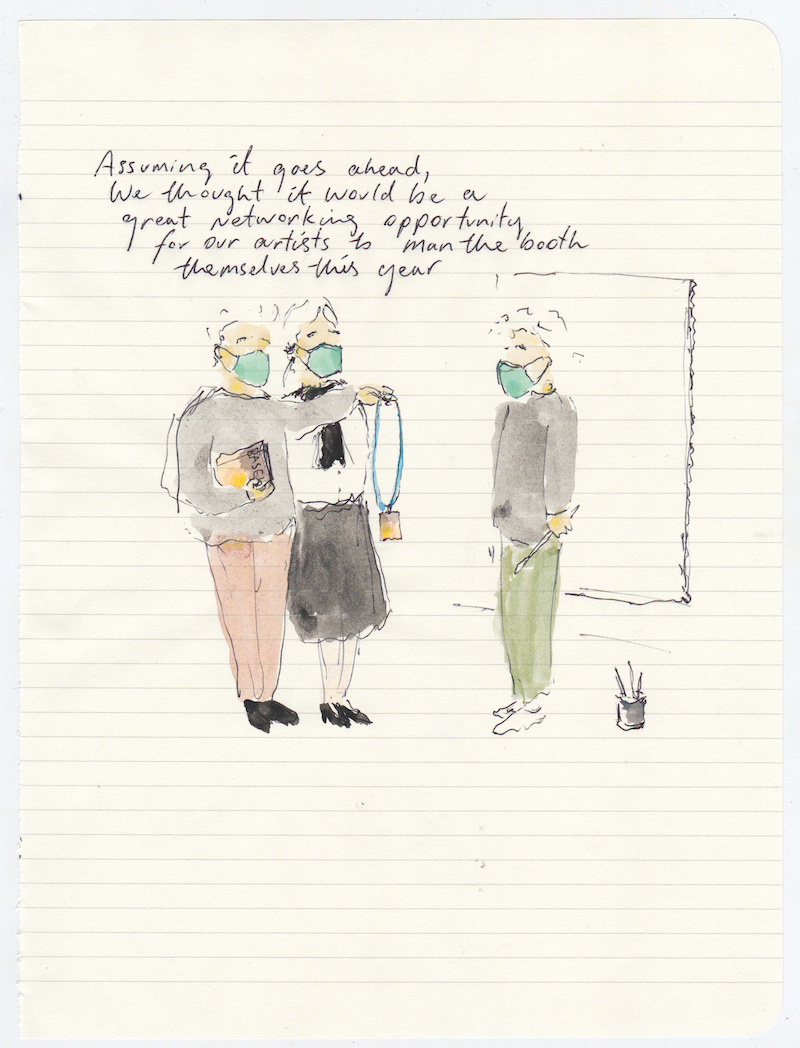

This is the basic business of the gallery, and for artists it’s also the basis of planning around their regular art-related income [bearing in mind most artists have at least a few jobs on the side]. The luxury of press coverage and the establishment of a relationship between a critic, arts writer and/or respected art magazine, is also something an artist expects of their dealers. And where art fairs, international representation and support for participation in exhibitions around the world were once the preserve of a select few Australian commercial galleries, it’s now the basis of day-to-day business for even mid-range operations.

Artists also like a dealer who’s cool with the artist having a show in another state or city. In return, the gallery usually asks for a slice of the artist’s art-related income [starting at 40% and up on in-gallery shows], and sometimes a piece of the action when an artist wins a prize [usually at the gallery’s commission rate].

Andrew Frost

Brand Building

Brand building is conventionally a crass concept, but, in contemporary art, all the best galleries take the task of creating a seductive aura around their artists very seriously. Committed dealers will develop a coordinated, strategic approach to building an artist’s profile and reputation. This will require them to do the hard yards developing meaningful relationships with pre-eminent writers, critics, curators and scholars who can contribute to the prestigious publications and curate the museum shows needed to establish and maintain a high-end brand. The best gallerists will think nothing of spending big on producing quality publications – from catalogues and coffee table books, magazine profiles, art journals and academic scholarship. Leading international galleries are going one step further, producing their own in-house magazines – perhaps the ultimate form of brand promotion dressed up as critical discourse.

So, what happens to this traditional approach to public relations when the artist can do it themselves? Through the power of Instagram, artists are increasingly cutting out the middleman and creating audiences for their work, engaging directly with arts professionals, even coordinating exhibitions with galleries. This is where the brand building that high-end galleries do for their own name kicks in. Because all the leading international dealers are now household names in their own right, it is still in an artist’s interest to show their work with a leading gallery, if only for cross-promotional purposes.

Carrie Miller

Unwavering Support

A key difference between a principled gallerist and their corporate counterparts is an undying commitment to the critical value of an artist’s practice. A good gallerist will spend endless amounts of time and energy making the case for the “artistic integrity” of the work to even the most baffled collectors and hostile critics.

And when one of their artists finally becomes a critical and commercial favourite, then inexplicably changes direction back to something no-one wants or understands, the best galleries will simply redouble their efforts to support that artist. They will carefully manage any downshift in professional relationships and develop a radical new approach to communicating the value of the work.

This unwavering commitment must also extend to managing the fallout of any number of personal challenges commonly associated with artists noted for said “artistic integrity”. When they get arrested for drink driving, need to spend time in a mental health facility for “exhaustion”, or leave their wife for a young gallery assistant and get into a messy child custody battle, a devoted gallerist will be there, every misstep of the way.

The artist’s death shouldn’t be the end of a gallery’s unwavering support, either. A committed gallerist will faithfully tend to an artist’s legacy well after there is anything in it for them, patiently dealing with fighting family members and the flood of fakes dumped on the secondary market.

In today’s fickle world, where loyalties can change more often than Kim Kardashian at a photo shoot, this ride-or-die mentality of high-end dealers is sadly being lost. Some new kids on the block – dealers who haven’t lived long enough to have lived through the decades-long, dramatic arc of an old school artist-dealer relationship – won’t commit to anything beyond a show. It’s like the difference between a Tinder hook-up and an arranged marriage.

Carrie Miller

Payment

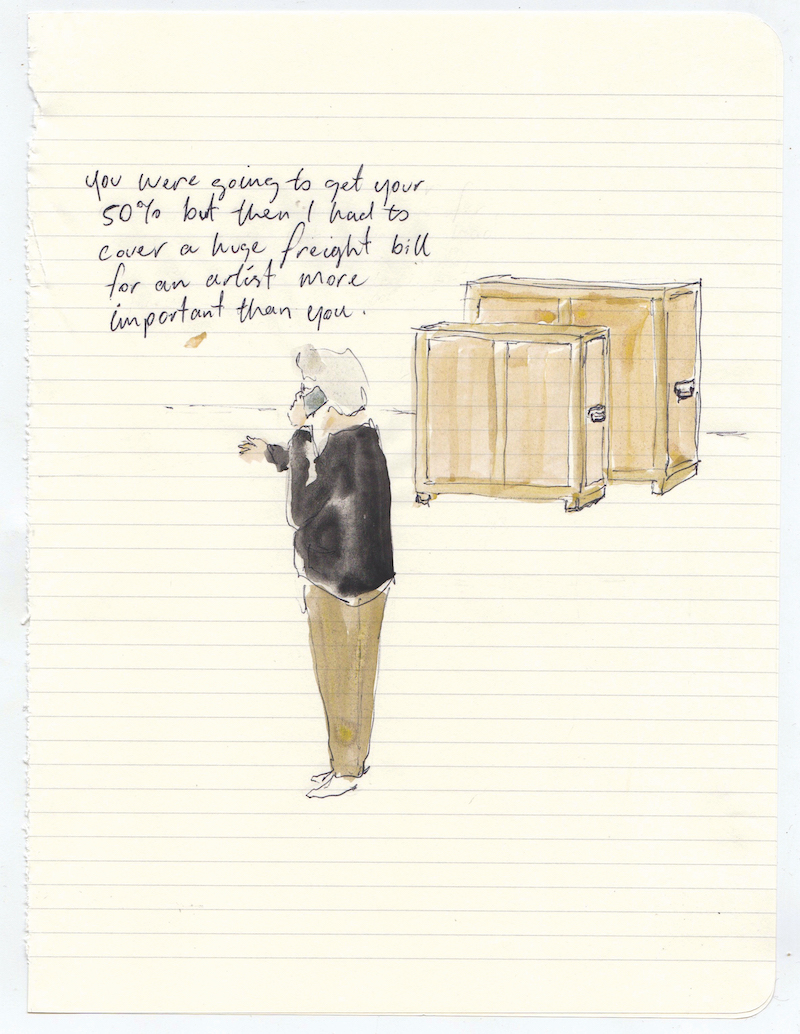

An almost universally accepted principle is prompt payment on the sale of art. That most artists are willing to allow leeway on this principle is a testament to both the enduring artist-gallerist relationship and the reality of the time it can take for the collector to pay the gallerist to then pay the artist. While the collector is taking their time, the artist would hope the gallery is solvent enough to cover their costs.

Also, in their dreams, artists hope gallerists can float them a loan for materials, pay an advance on sales to cover financial shortfalls, and pick up the tab for transportation costs when the artist has a sweet gig in a regional gallery.

It’d also be nice if artists could continue on their merry way making their art while less prestigious but better-selling stablemates rake in the cash for the gallery. And while selling is the name of the game, artists expect a degree of decorum from their dealers, which means no unauthorised selling of their work on Artsy, no Winter, Summer or March Madness discounts, and under no circumstances should the gallery conduct a BOGOF sale.

Andrew Frost

Placement

A committed gallerist demonstrates a faithfulness to an artist that extends beyond the financial. They work to build an artist’s cachet and reputation to ensure collectors remain in an artist’s orbit and invested in their ongoing development. Part of this mission involves placing an artist’s work in strategic public and private collections to build advantageous fanfare around an artist’s practice — using these opportunities to verify an artist’s aesthetic appeal (and perhaps cynically, investment promise).

Once a collector purchases a work, they own it. A gallerist’s or artist’s only means of controlling it — ensuring that artworks are loaned for exhibitions and even displayed correctly in the collector’s home — is the extent to which the collector values their relationships with artists and dealers, and their reputation. So much of a gallerist’s work is done in advance of a sale, vetting who can own what by whom. Much of this decision making is based on the ideas and discussion between gallerists, collectors and artists. In a way, there’s an interesting relationship of courtship and trust at play, where each actor works to understand the other’s hand and their intentions with owning and selling a work of art.

In the last recent few years, there have been major shifts in how art is being collected, impacting the traditional long-term relationships between dealers, artists and collectors. An example that springs to mind are online galleries and artists selling direct, including Instagram sales. These avenues bridge a gap in the market, catering to people who want original art, but don’t wish to pay the overhead costs charged by an established gallery. Certainly, it’s part of the democratising of art and great in the sense that it supports original content (much better than buying a poster of a Monet) while demonstrating that one doesn’t need to be a millionaire to buy art. But buyer beware. Be sure to emphasise long-term relationship building with a gallery over a bargain sale on social media. It will put you in much better stead when that gallery picks up the next Instagram star.

Micheal Do