On Liking it Before it was Cool

In this third of an ongoing series on her highly intriguing ethnographic study of the New York art world, Hannah Wohl explains her concept of creative vision as it applies to the endeavours of art collectors.

Words: Hannah Wohl

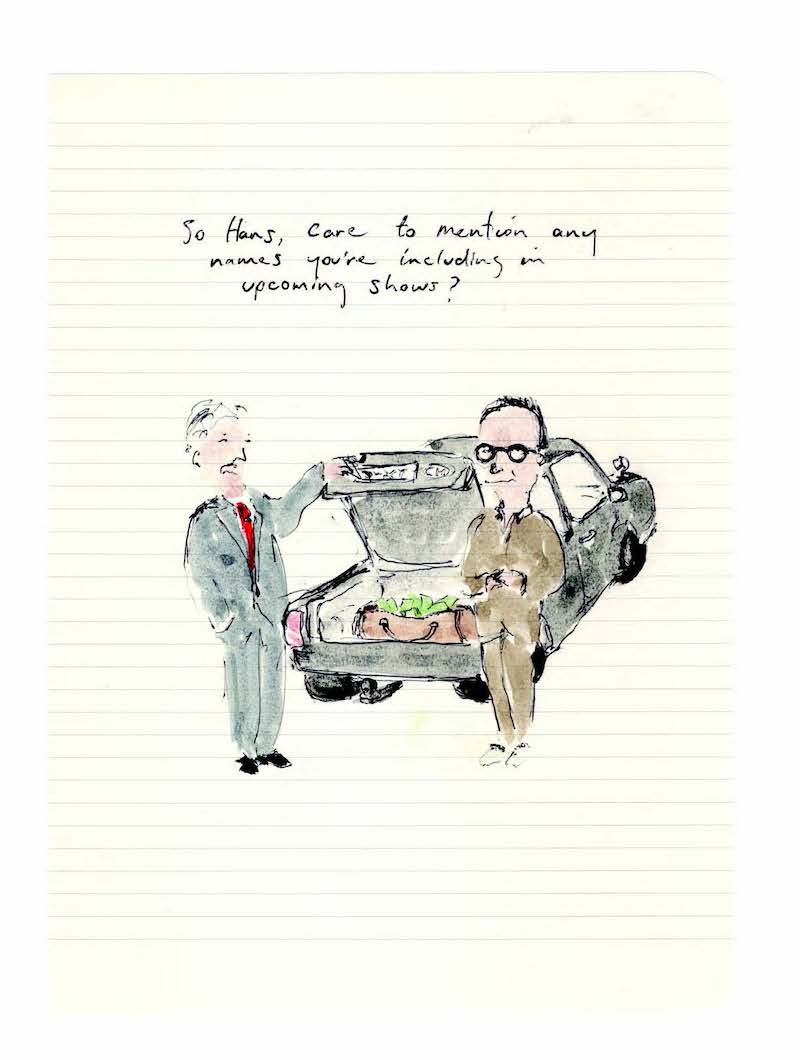

Illustrations: Coen Young

In the contemporary art world, where anything – a giant hamster wheel or woven pipe cleaners – can potentially be a work of art, how do collectors select works and how do they justify their decisions to others? In my book, Bound by Creativity: How Contemporary Art is Created and Judged, I set out to understand how people evaluate contemporary art. Over the course of two years, I interviewed more than 100 artists, dealers, curators, collectors, and art advisers and observed people interacting in countless studios, galleries, museums, and collectors’ homes in the New York City art world. I learned that, faced with uncertainty, art world members orient their aesthetic judgments around perceptions of creative visions – enduring and core consistencies within bodies of work.

Collectors want to own work that they view as embodying a distinctive creative vision. This takes some expertise. They have to know which contemporary artists are seen to have an especially original creative vision and what elements are iconic of this vision, so that visitors can look at their walls and say, “That’s a Mark Bradford,” or “That’s a Julie Mehretu.” However, collecting the most iconic work of blue-chip artists is not enough to be validated as a good collector. Collectors are also expected to express their own creative vision through the display of their collection. Just as an artist has an oeuvre and a dealer has a gallery program, a collector has a collection. As a collection is comprised of the work of multiple artists, it may be tied together through somewhat looser threads than a single artist’s oeuvre, but collectors still conceive of their collections as adhered by their distinctive aesthetic sensibilities, and, like artists, they view these aesthetic sensibilities as derived from their identities.

How do collectors build a collection that they and others will view as economically and aesthetically valuable, while also representative of their unique aesthetic sensibilities? The former involves collecting in demand work by high-status artists, while the latter involves collecting unusual works by lesser-known artists. Collectors purchase these works at different price points. When they buy works that are expensive, relative to their collection, they find it especially important to purchase works that are iconic of an artist’s creative vision, and they are only likely to purchase more idiosyncratic works if they already own the artist’s iconic work.

In contrast, collectors view relatively inexpensive works by emerging artists as less likely to retain economic value, so collectors consider these works to be fliers and are more willing to purchase one-off idiosyncratic pieces from these artists.

Collectors use both iconic works and fliers to communicate their broader orientations toward collecting. Their private collections are somewhat public in that they frequently host art world members to show them the newest rehanging of their collection and will loan works out for exhibitions. They tend to hang works of different price points in equally prominent positions, and they explain to guests that they value their collection for its aesthetic value, not its economic value. In their narratives about their collections, they seek to reinforce their legitimacy as good collectors.

Key to collectors’ narratives are claims of what I call aesthetic confidence, or an expressed willingness to purchase works based on a belief in one’s distinctive and independent taste. Elite art collectors are not the only people who claim aesthetic confidence. A music aficionado might similarly brag about listening to a band or seeing them in concert before they were famous. Across cultural fields, people claim cultural expertise and legitimacy by arguing, “I liked it before it was cool.” But collectors go a step further because they claim that they are willing to put money down, sometimes a lot of money (even if disposable income), on their belief in their independent taste. Collectors particularly emphasise that they often purchase works early in artists’ careers, and they highlight examples of specific artists who later went on to greater critical and commercial success. As one prominent collector I interviewed stated: “I have confidence. I buy what I like and hang it on my wall, and if you don’t like it, that’s okay with me. If you do like it, it’s fine with me too. I don’t ask permission… But a lot of people follow, and because we have a very public collection, and because we are confident, and we purchase things that don’t need a stamp of approval – these things that are very early – and then other people jump in and comment and pick things up. I guess you default to being a tastemaker.”

But claims of aesthetic confidence are flexible. Collectors assert that they bought early, while pointing to different benchmarks in artists’ careers. Is it still early after the first solo exhibition at a major gallery, or the first museum acquisition, or the first biennial? Collectors also account for artists’ career trajectories after their purchase in ways that flexibly legitimise their taste. While collectors use artists’ later success as evidence of being a tastemaker, they argue that career failures are evidence of their superior taste as well. In their telling, they are sometimes so far ahead of the curve that the market still has yet to catch up.

The problem with aesthetic confidence is that, while anyone can claim it, not all claims are equally accepted by others. Collectors accept or reject each other’s claims of aesthetic confidence in ways that reinforce status hierarchies among collectors. Higher status collectors particularly scorn those who use art advisers, accusing these collectors of having to buy their taste instead of naturally possessing it. They argue that they themselves have no need for these formal recommendations, as they buy with their eyes and not with their ears. But elite collectors actually receive a steady flow of chatter as they trade information with collectors, curators, dealers and others in the art world. It is the informality through which they receive these recommendations due to their centrality within the art market that allows them to downplay the receipt of this information. It is worth asking: Who gets to like it before it was cool?

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 103, January to March 2023.