Cultural Capital: What is Creativity?

In this second of an ongoing series on her highly intriguing ethnographic study of the New York art world, Hannah Wohl explains her concept of creative vision as it applies to the endeavours of visual artists.

Words: Hannah Wohl

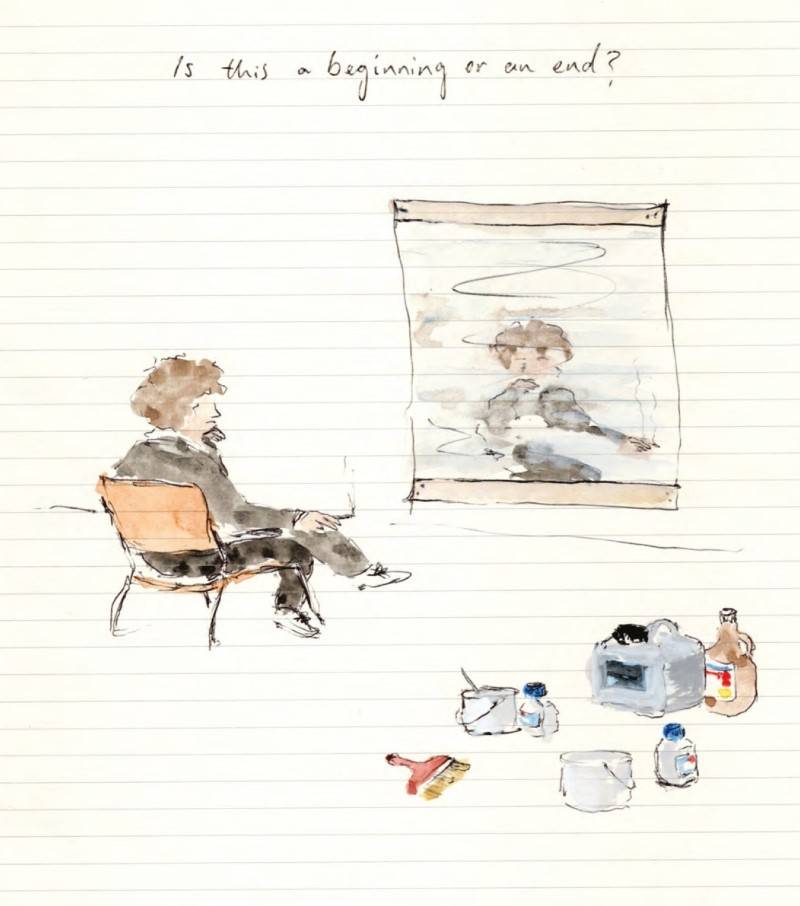

Illustrations: Coen Young

In the contemporary art market, anything can potentially be exhibited or sold as a work of art. A work of art can be a painting, a mundane found object, or even a set of instructions. The scope of potential themes or topics of what art can be about is equally wide, from social issues like colonialism to emotional states such as nostalgia. In all markets, transactions must take place, and the contemporary art market is no different. People must interpret and evaluate artworks in order to decide which artworks to exhibit and purchase.

As a cultural and economic sociologist, I have been fascinated with how people make aesthetic judgments in the face of uncertainty about what constitutes good art, or even art. This question inspired my book, Bound by Creativity: How Contemporary Art is Created and Judged, for which I conducted over 100 interviews and more than two years of ethnographic research in the New York City contemporary art world. I was particularly intrigued by how artists make decisions during the creative process.

I spent countless hours with artists in their studios, flipping through sketchbooks and rummaging through storage closets, as they told me about how they made specific choices about which sketches to turn into full-scale works, what was the next step in executing a work, when a work was finished, and when to abandon an unfinished work.

I realised that artists faced two kinds of uncertainty in the create process: an evaluative uncertainty about what kind of work was worth making and a material uncertainty about how the work they envisioned would appear upon completion. These uncertainties were not visible in the polished works hanging on gallery walls or accompanying confident press releases and artist statements, but they were the major questions artists grappled with in their daily work.

When I asked artists about how they made creative decisions, I received refrains that seemed trite: “It is intuitive,” “I just know,” “It works.” As a sociologist trying to analyse specific creative decisions, these responses initially frustrated me, but I gradually came to appreciate what artists were trying to tell me: The creative process was intuitive, and particular emotions drove it.

Artists begin the creative process with what I call “low-stakes experimentation,” in which they conserve time and materials by using fast and inexpensive processes of production to rapidly test ideas. For some artists, like those who make works with small found objects, low-stakes experimentation encapsulates the whole process of production, whereas artists who use time-consuming processes of production and expensive materials do extensive low-stakes experiments with sketches and models. Artists find inspiration in both their previous work and from diverse sources, from encounters in daily life to Instagram searches. They seek formal techniques and conceptual themes that they feel are related to their broader creative vision, as materialised in their body of work, such as everyday materials or the concept of domesticity.

As artists incorporate these ideas by experimenting with different media and techniques, they react emotionally. Artists express that they experience ambivalence toward their work when they feel that the experiment is dissimilar to their previous work but are unsure of its relevance to their creative vision. When artists experience ambivalence, they pause production of their work until they feel that they can explain the connection between the new work and their creative vision. Often, these works remain incomplete, eventually landing in a storage unit or garbage can. Other times, artists resolve the connection and complete the work. In contrast, when artists believe that the experiment incorporates new elements while still relating to their creative vision, they explain that they feel excitement. Excitement then serves as an impetus for artists to experiment further with the new element, sometimes by developing multiple works into a series.

As artists progressively experiment with more variations of elements that excite them, they hold some elements constant (such as using the same painting technique) while varying other elements (such as using different kinds of varnish) in order to see their effects. Through this process, they develop what I call “creative competencies,” or improved predictions of material results. Artists develop creative competencies not only in formal techniques, but also in conceptual understandings, such as gradually conceiving of the connection between a material and the concept of mass production. Skeptics of contemporary art sometimes dismiss it with the verdict, “My four-year-old could do that.” But contemporary artists would push back, believing that even seemingly technically simple processes require a long process of low-stakes experiments in order to understand how the form embodies the conceptual idea and how the conceptual idea connects to the broader creative vision. In essence, artists would argue that the four-year-old has not developed creative competencies.

Yet in developing creative competencies, artists also risk a third key emotion: boredom. As artists increasingly develop creative competencies, they are able to better predict the material result and conceive of its conceptual meaning. When artists no longer experience surprise, they become bored. The problem of material uncertainty now becomes a problem of material certainty. Artists tend to stop producing elements that elicit boredom, which spurs a search for new elements through renewed low-stakes experimentation. The creative process is a creative cycle, driven by emotional reaction.

When we think about creativity, we tend to imagine bursts of inspiration that arise in sudden, lightbulb moments. But the creative cycle is a slow burn. Rather than eureka moments, artists develop ideas through an iterative process in which they test out new elements and repeat elements that elicit positive emotion. Artists stabilise material uncertainties by using low-stakes experiments and developing creative competencies. Artists manage evaluative uncertainties by relying on emotions to interpret what is relevant and interesting in the context of their specific bodies of work. Emotions provide a charge that gives direction and force to the artistic decision, and justifying the emotion provides the decision staying power. In the absence of objective criteria by which to judge their work, emotions serve as fulcrums for aesthetic judgment.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 102, October to December 2022.