Cultural Capital: Why Do People Collect?

Is it a quest for immortality? Or a quest to match your couch? In the first of this three- part series, Andrew Frost and Carrie Miller discuss some of the reasons people collect art.

Words: Andrew Frost and Carrie Miller

Illustrations: Coen Young

THE QUEST FOR IMMORTALITY

There was time when rich people were en- tombed with their possessions. As their servants piled their belongings, knick knacks, art collections, golden boats and mummified pets into the tomb – and just before they drank the poison that’d ensure they’d be on hand for their former masters in the afterlife – they must have thanked the gods for their fortune being born to serve those high-ranking patrons of culture.

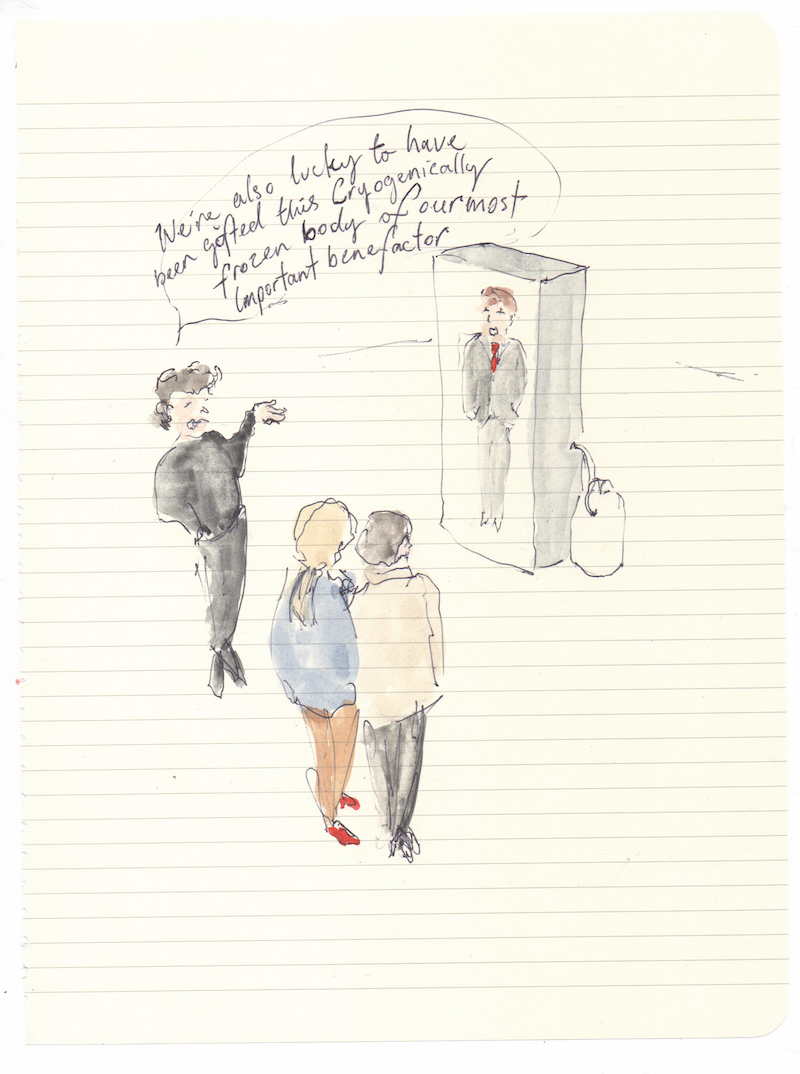

Of course, these days people don’t tend to be entombed with their stuff. Instead it’s all given away while they’re still alive. This has two major advantages: the tax breaks that make donating substantial art collections so much easier to bear; and the keen sense of appreciation felt by the public, paid back in spades by widespread adulation for the donor.

Once upon a time people donated their art to museums. Australian arts patrons and col- lectors whose donations either founded or bolstered Australia’s art museum collections include the likes of Fay, Smorgon, Fairfax, Schaeffer, Cruthers, Hinton, Power, Reed,

Coventry, Kaldor, and many others down the decades – not that everyone who sees the art they donated will remember their names be- fore the artists who made the work itself. But still, it’s nice to be reminded why sometimes we really can have nice things.

Another way to achieve a kind of proximate immortality is to get involved in the making of art. Or if you’re really ambitious, in the making culture itself. The old way was to commission artists to paint your portrait, or the portrait of the board members, or a portrait of the lady wife who died tragically young in a freak accident during a routine liposuction. But history – and portrait prize competitions – have proven that we only really appreciate portraits of royalty, artists, gallerists or pop stars after they have died.

Nowadays smart art collectors yearning for immortality will put down their cash for building big expensive art museums, or for a series of site-specific sculptures that will be sited on public land. They will appoint curators to choose which over- seas artists are good enough to make works here, or they will corner the market on art from Cana- da and build a beautiful giant warehouse conversion that not only functions as a home for their Canadian art, but that will be the anchor for the gentrification of a formerly foul-smelling factory district that did nothing more than make beer for the working class, but is now the sparkling centre of a city that looks like the world of tomorrow.

But the smartest way to achieve immortality is to create a cultural program. What is a cultural program? No one knows, but we will be thanking whoever put it together as we are sealed inside their glittering tombs of fame.

Andrew Frost

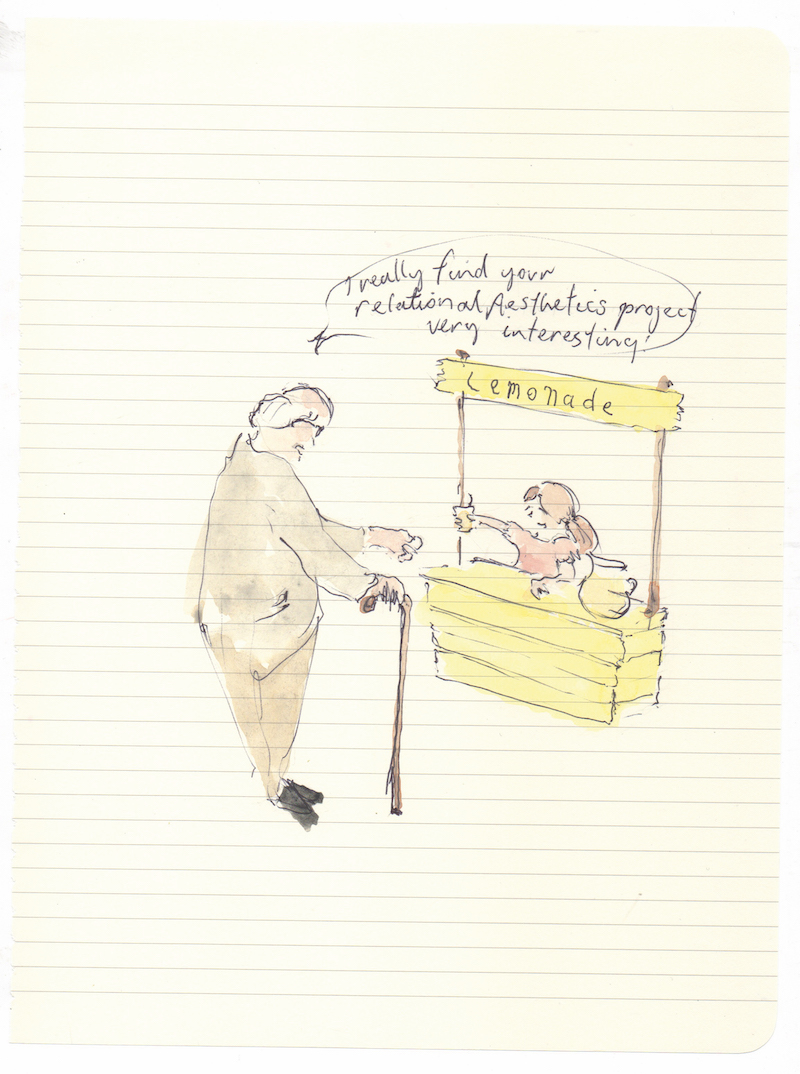

THE DESIRE TO SUPPORT THE ARTS

Herman Goring once famously claimed: “When I hear the word culture, I reach for my revolver.” If he was an Aussie, he might have reached for a footy instead.

Australians have traditionally been a famously, proudly, uncultured lot. Some of us in urban centres like to think that’s changed, thanks to us. But connoisseurs of cold-pressed juice and craft beer who attend plays at the local avant-garde theatre company and who never miss a writer’s festival still take a mocking tone when it comes to contemporary art.

So, for those few collectors who commit them- selves to supporting a form of culture that nearly everyone thinks is a load of bollocks, we salute you. Some of these collectors are already outsiders, part of the fringe cultures themselves. For them, supporting the arts is a natural extension of who they are. They intrinsically value indie cultural producers, particularly those who are the least understood. They are comfortable in studios that look like serial killer dens, where half-drunk beer bottles serve as ashtrays. They enjoy bearing wit- ness to long, drug-fuelled monologues by self-obsessed artists about their existential struggles and are sympathetic to their need for $50 to “buy some materials”.

The importance of these collectors is their invaluable support of unrepresented artists at the beginnings of their careers. Increasingly, there is another sort of collector in contemporary Australia: the collector-philanthropist, who is splashing significant amounts of cash to support the sector as a whole. Whether it’s by ponying up the funds for a major museum acquisition, underwriting a prize, or even contributing financially to the bricks and mortar needs of a public gallery, these benefactors passionately believe in the higher social purpose of a man nailing his arm to a wall for 30 hours.

For these collectors, it must be a bitch explaining to colleagues and friends their commitment to investing in the contemporary art sector as a more meaningful way to contribute to society than through the benefaction of their kids’ private schools. They learn to cope with the awkward silences when their dinner party guests gawk at the badly made video playing on a loop in the hallway.

That’s because they are confident in the knowledge that for culture to thrive, rich people need to do more than attend charity fundraisers for the lo- cal ballet company. And that, one day, those dinner party guests will go to one of those fancy fundraisers held at the new wing of a museum… and it will have their name on it.

Carrie Miller

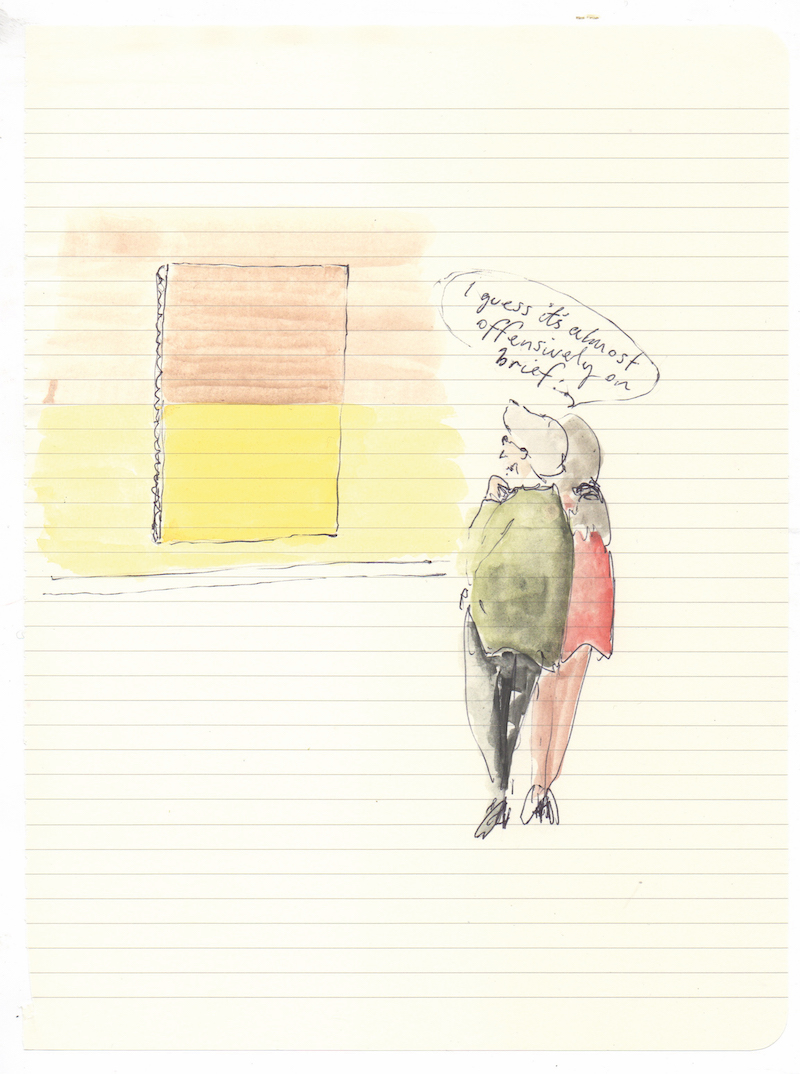

DECORATION

Who doesn’t like nice things? Our preoccupation with acquiring these things allows us to deny the arbitrary and contingent nature of human existence in the face of a cruelly indifferent universe, while at the same time giving us stuff to post on Instagram.

Of course, people who care about fine art – even those of us postmodernists who bang on about how the distinction between high and low forms of culture is just a “social construct” – want to think it’s a special form of culture and not just another type of beautiful commodity. We wouldn’t be caught dead with a framed print of a Matisse exhibition hanging on the wall of our office, except as an ironic statement about the commodification of beauty.

We certainly don’t approve of people who reduce fine art merely to its banal aesthetic appeal. That said, art collectors who are not so concerned with cultivating their minds are extremely helpful to the rest of us. They don’t get angsty about the relationship between art and commerce, which allows contemporary artists to do a sideline in pretty objects while still maintaining the integrity of their conceptual practice.

People who collect art for its visual appeal tend to consult interior designers about how to “curate” the spaces they live and work in. They think about old-fashioned things like co- lour, composition, texture, even scale (“will it fit above the Le Corbusier couch???”). They may even talk about “bringing the space to life”.

(Don’t be afraid, it’s a phrase they saw in a copy of Belle at the offices of their financial advisor.) Big, abstract paintings and imposing photo- graphic work are the go-to art pieces for decorative collectors. Depending on the colour palette of their interiors, these works will tend to be either boldly colourful or monochromatic. When their homes appear in magazine spreads, these works will look spectacular in the back- ground of a casual portrait of the collector and his family – a stylish counterpoint to the casual elegance of his partner, the messy sweetness of their tow-headed infant, and the scruffy indifference of their three-legged rescue puppy. Let’s face it, the radically disruptive possibility of anti-aesthetic art is fine in principle. But confronting the brutal truths of existence can be a real bummer after a long day making money. You deserve to go home to that beautiful house.

Carrie Miller