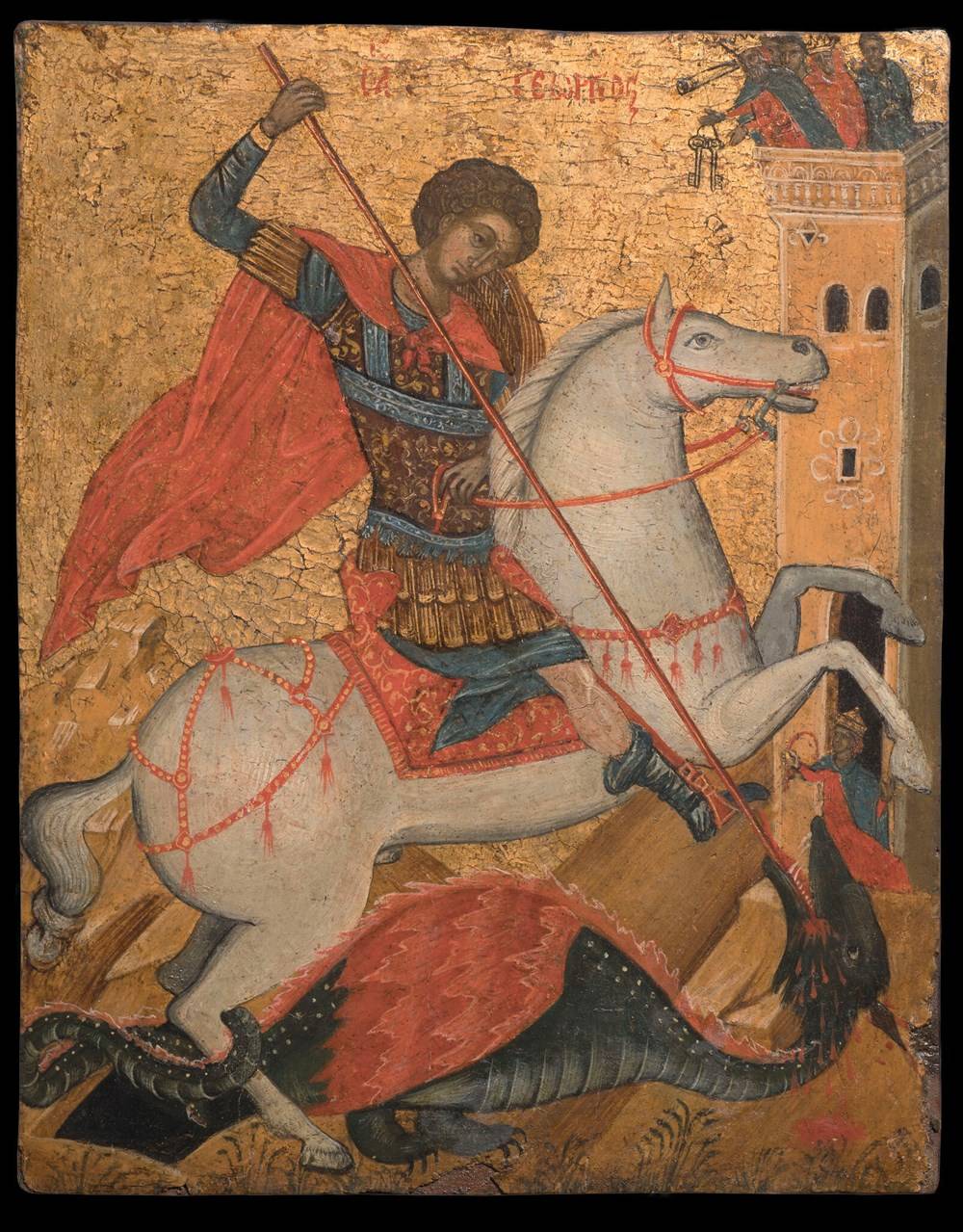

Saint George and the Dragon, Crete, c. 1500. Courtesy: private collection, Canberra, and Mona, Hobart.

Mona has given you plenty of exhibitions that are all new art; and several, as the name promises, that combine old and new. But this is the first exhibition at Mona of just old art, specifically, artworks made between 1350 and 1900—the same centuries where western art history includes Leonardo da Vinci, Velasquez and Monet. Heavenly Beings: Icons of the Christian Orthodox World takes a different route to the past.

Heavenly Beings provides a journey into a spiritual and aesthetic tradition, revealing the deep roots of Eastern Christianity. Although it may seem to be a scholarly art historical exhibition (and it is, thanks to its initiating curator, Dr Sophie Matthiesson, and contributors to a richly detailed catalogue), it taps into something we have been thinking about a lot here at Mona: the ultimate biological motivation for things we earthbound beings do. We can assume that religious belief, as an apparently universal human phenomenon, is both grounded in our biology and expressed by culture in potentially infinite variety. All cultures, it seems, make certain objects and activities ‘special’; sometimes as in-group ritual behaviour (showing who’s in, and who’s out); sometimes for supplication, believing in agency where there may be none.

The earliest Christian icons drew on ancient traditions of image-making and worship through sacred imagery. In the eighth-century words of St John of Damascus, ‘We venerate images; it is not veneration offered to matter, but to those who are portrayed through the matter in the images. Any honour given to an image is transferred to its prototype.’ This is why there can be thousands of copies of a popular prototype: think of the preeminent image of Christ seen throughout mediaeval Christendom, the miraculous icon of his face imprinted on a cloth, called an acheiropoietos (Greek for ‘not made by human hands’). Some very special icons were considered miraculous ‘wonder working’ power objects. All are precious to believers, so often handled—for just a touch of their divine essence—that the egg tempera paint may wear away.

Almost all the icons you will see at Mona date from after 1453, when the first Christian empire, the Byzantine empire founded by Constantine the Great, fell to the Ottoman Turks; but they carry within them the rich, complex legacy of the religion that had been nurtured across that vast and powerful realm for more than a millennium. The exhibition charts the continuity and vitality of icon painting wherever Orthodox Christianity took root after the events of 1453, notably in Russia, Crete and mainland Greece. There are icons by masters from the great Cretan workshops, whose holy subjects vibrate with life against shimmering gold leaf surrounds. A number of Ethiopian, Egyptian, Syrian, Balkan and Palestinian icons are vivid reminders of the many other icon traditions that flourished throughout the far-flung Orthodox world. There are variant images of Christ the Saviour, Mary ‘Mother of God’, and their holy feast days. Guardian saints, beloved as healers, warriors and consolers, include Nicholas (protector of sailors, merchants, archers, brewers, reformed thieves, prostitutes, pawnbrokers, unmarried people, students and children), George (with and without the dragon), more than one John, and Paraskeva, among the most popularly venerated female saints in the Orthodox Church. Things from Mona’s permanent collection include an eighteenth-century proskynetarion, the personalised souvenir of one devout Christian pilgrim’s journey to the Holy Sepulchre inside the walled City of Jerusalem.

Painting an icon may begin from an act of piety, but the resulting object also lives as a work of art far beyond its original religious purpose. We can look at the icon as a ‘window into heaven’, as believers believe; but also as a looking glass, through which we may glimpse the deeper purposes—deeper than awe and transcendence, than culture or a higher power—that are served by human creativity.