In the Works: Art history 101

Visual arts 101: Lessons on influential works and their significance.

Words: Edward Colless

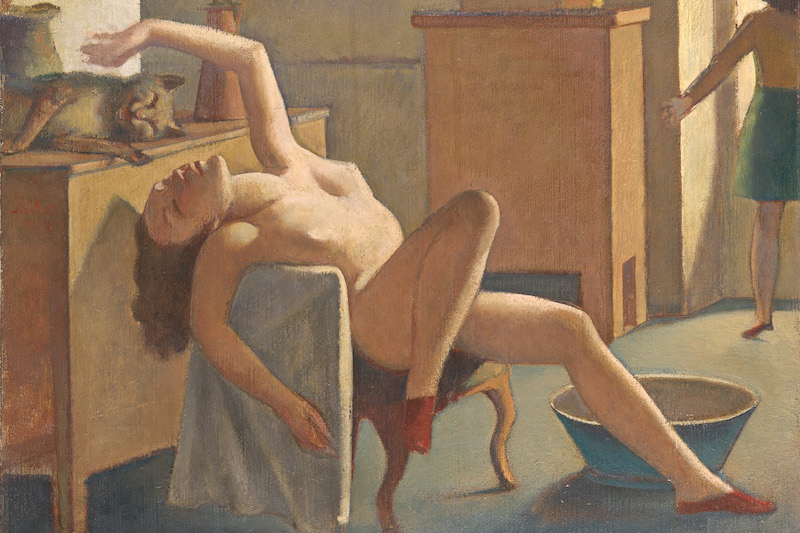

SHE IS ARCING BACKWARD in self-satisfied languor, draped across an armchair like casually thrown clothes, to loll in the room’s lazy warmth while groping ineffectually in the air for that impishly grinning pet. Is this episode in pubescent sensuality, and especially its unashamed arousal, a warped fantasy on Alice’s rendezvous with the Cheshire Cat in Wonderland? With scenery and skin stripped down to untarnished geometric volumes soaked with an almost anaesthetising light that condenses like ether, this is no simple or cavalier excuse for vindicating female nudity as spectacle. Nor is it just serving up the overcooked sexual allegory of feline luxury. Balthus’ 1949 painting Nude with Cat – despite its bland title and modest size – is a volatile phantasm: hallucinatory, hypnotising and captivatingly unsafe (mercifully, it has found sanctuary in the National Gallery of Victoria).

At first glance the nude figure’s pose might seem as lethargic as an oriental odalisque, and designed for display. Look again: the limbs and torso twist into jutting, angular and even dislocated joinery in a muscular as well as nervous spasm. This posture suggests an ecstatic seizure, like that of Bernini’s sculpture of St Teresa of Ávila floating in an ambiguously spiritual rapture on a cloud. But Teresa’s body liquefies under the sensuous stroke of her God’s angel; here the pliant yet exaggerated bulge of the neck makes it sprout like a weighty tumour from between the shoulders. This nude’s angel – or cupid – is a Goya-esque demon cat. Or perhaps it’s the girl looking out the window, distracted and detached from the scene in the fore- ground and who – transfixed with arms and legs open – is on the brink of levitating. Something odd, murky and anxious is contorting this scene of so-called innocence awakening, turning the hospitable sultriness of la primavera spooky. This flesh is clay, thickening into an impasto crust the way heavy makeup dries out, and with an archaic austerity in tone and palette which Balthus readily admitted was derived from Italian Renaissance masters (his favourites, and you can tell it here, Piero della Francesca and Masaccio).

There’s mania locked up in this painting’s enigma. And it’s an enigma that corresponds with the artist’s persona. Balthus was the pseudonym adopted by Balthasar Klossowski, when he didn’t go by the invented title of the Comte de Rola or wasn’t claiming to be a descendent of Lord Byron (among other aristocratic fantasies). For a personality prone to voluble counterfeit identities, Balthus was mysteriously reticent about his own work and was socially remote, even hermit-like. So much about his character and artistic ambitions put him at odds with the modernist ethos of innovation and revolution, leaving him unclaimed by any vanguard style or movement (even the Surrealists, with whom – like the uncle of the young model in this painting, the French intellectual George Bataille – he is often unconvincingly matched). He was indisputably a major figure of 20th-century art, if idiosyncratically aloof from and indifferent to it; and his influence has been likewise elusive and eccentric.

If there is an elusive and eccentric Australian artist who has comprehended and convoluted Balthus’s murky classicist innuendo and brooding sexual jeopardy then that has to be Anne Wallace. For more than two decades her paintings have detailed a world of unspoken but fraught erotic confrontations, implicated with melodramatic coercion, cunning and aggression, and with haughtily perverse pleasures. Captured like film stills from inaccessible yet disquieting domestic narratives, her incidents seem at once casual and tense, undercut with guilt, accusation, temptation and distress.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 90, OCT – DEC 2019.

Image: Balthus, Nude with Cat (Nau au chat), 1949. Oil on canvas, 65.1 x 80.5cm. National Gallery of Victoria Collection. Felton Bequest, 1952. Courtesy: the artist, ADAGP, Paris and NGV, Melbourne.