Cultural Capital: Rules of Engagement

How (not) to talk to an artist about their work.

Words: Andrew Frost, Carrie Miller, Tai Mitsuji

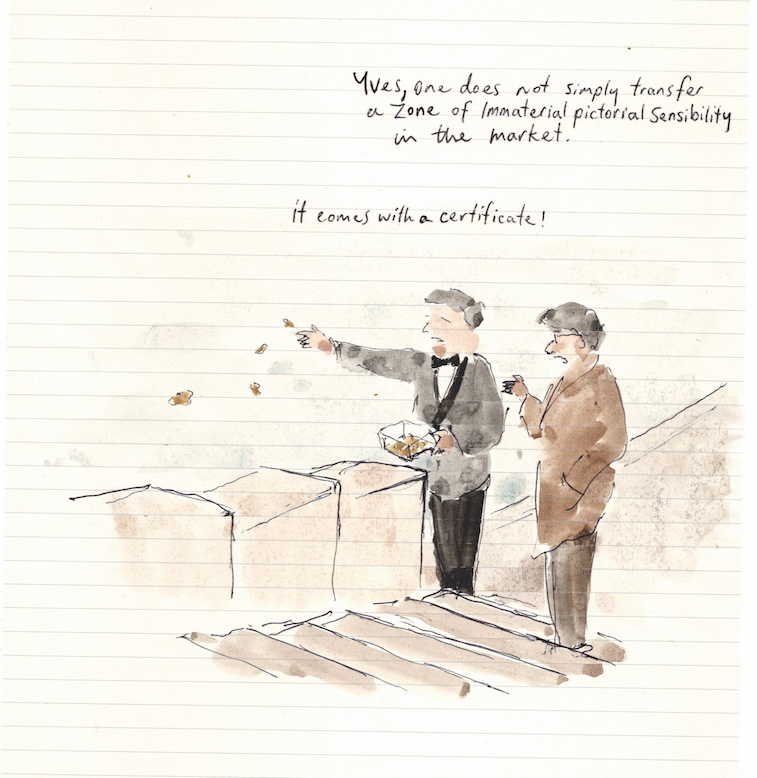

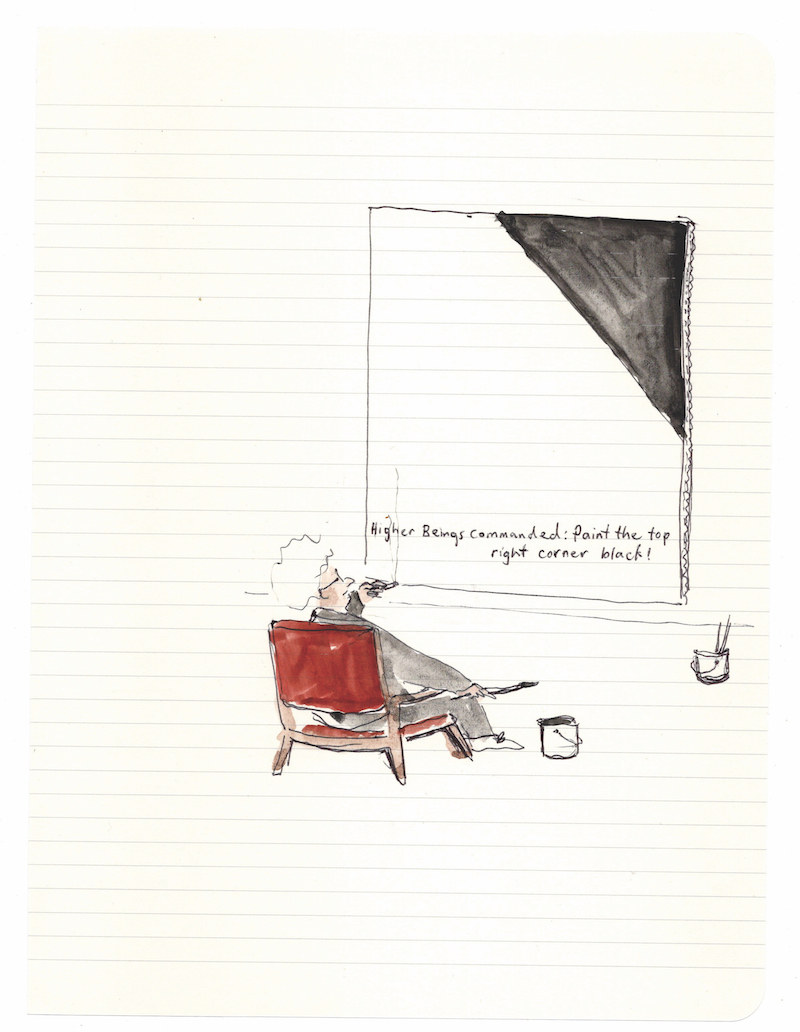

Illustrations: Coen Young

RULE ONE: Don’t turn the artist’s work into an extended bibliography

We’re often told that originality is dead. Every jaded art school lecturer seems set on branding this understanding into their fresh-faced grasshopers. To talk of originality is to become a pariah – or, worse, one of the uninitiated. What a tedious state of affairs.

The reality is that no one really likes their work to feel unoriginal. No artist wants to be reminded of the long list of artworks that preceded theirs, nor do they want their work to turn into an extended bibliography. “The drips are just like Pollock’s”; “it’s clearly a riff on Kahlo”; “this is a 21st century Caravaggio”. Oh, shut up.

Of course, a one-off comparison can be flattering – after all, it briefly places the artist in the pantheon of past talents who only require a last name to be identified. But with every subsequent citation, sweet intentions turn more and more sour. Don’t treat their work like a Buzzfeed quiz: a series of inane questions that reduce the diversity of the human condition down to 10 possible answers (I got Matisse, FYI).

Treat it as you would a newborn baby – you can recite poetry to it, make cooing noises, or just stare lovingly at it. Just don’t call it Pollock.

Tai Mitsuji

RULE TWO: Don’t ask how long it took to make

Remember that scene in Goodfellas where Henry says to Tommy that he’s a funny guy and Tommy flips out? Well, asking an artist “how long did this artwork take to make?” will likely elicit the same response, although, unlike in the movie, it won’t all be fun and games. The answer to that question is always the same, whether the artwork is just a little pencil squiggle on a Post It note, a found object, or some massive painting in a heavy gold frame…

How long did this take to make? How long? It takes a lifetime of practice. Making things requires perseverance and skill because creating takes a huge amount of effort and a ton of self-belief. Regardless of whether something took five minutes or a year or more, making the end result took years of education and practice. An artist doesn’t just arrive a professional level of confidence, a knowledge of their form, and an understanding of precedent by accident – it has to be learned. And it took untold hours of contemplation and persistence to arrive at that point. How long did it take? You know something? You’re a funny funny guy.

Andrew Frost

RULE THREE: Don’t ask for something more family friendly

As a serious art collector, we know you have a deep appreciation of the political significance of contemporary art. You have always supported work that breaks with habituated patterns of thought, challenges conventional moral norms, holds up a mirror to the ugly truths of mainstream society. It’s obvious by the casual way you wander past those giant paintings of vaginas that symbolically represent the collective power of the #metoo movement.

But you know that not everyone in your life is as culturally switched on. It’s natural for you to be concerned about how you’re going to explain the importance of those vaginas to the office staff who have to stare at them all day, or to your partner who has to field questions from a curious 10-year-old. The important thing is to push these anxieties down when enquiring about the work to the artist themselves. Don’t ever ask an artist if they have anything that might be a bit more palatable to hang in the office or the home. Not only will you risk the artist thinking of you as a hack, you will remind the artist of how pedestrian the public is and risk something much greater: getting a lecture on society’s moral failings from someone who should definitely let their work speak for itself.

Carrie Miller

RULE FOUR: Don’t ask if the artist has ever thought of making work that’s a bit more commercial

We can all agree that, in an ideal world, the value of art should be never be reducible to mere commodity. And we can also agree that, in an ideal world, art should be more commercially valuable than just about anything precisely because of its superior status to mass produced objects.

Artists, and by extension the art collector, is therefore caught in a double bind: wanting

their work to remain uncontaminated by crass commercial considerations and needing the art market to affirm its value through big sales. Never surface these tensions when in conversation with an artist who is struggling to gain commercial success. This is the job of their dealers, who will anxiously rehearse these conversations with their therapist over many months after the artist has had another

critically acclaimed show that sold nothing. As a dedicated art collector your job is to pump up the artist’s tyres by telling them their work is ahead of its time. Then you need to hope that a) the market eventually catches up and realises the artist’s genius or b) the artist gets desperate enough to sell out and make work with mainstream appeal that will raise the commercial value of the early, experimental stuff that you’re stuck with.

Carrie Miller

RULE FIVE: Don’t talk about anything and everything but the work

“I love the frames you chose for the paintings”; “what a beautiful gallery space you have”; “there are so many people at this opening!”. What is missing from these remarks? What essential element don’t we find in these effusive words? At any art event, you will hear some combination of these comments. What you are not hearing is anything about the art.

Yes, the art! The reason for the frames, the space, the people, and even the conversation you are engaged in. You should be wary of such misdirected compliments, when speaking with an artist. You know, those well-intended observations that avoid the art and betray your avoidance. Deployed with subtlety and tact, they may distract from your less flattering feelings. However, there is only so long that you can obsess over dry arancini balls and cleanskin wine, before something seems amiss. At some point, it becomes necessary to redirect your energy, look them in the eye and say something of substance. No one is expecting an extended speech, or soliloquy that invokes the heavens and redefines the earth. No, really, no one is expecting it – this is your moment to cause a stir. Or, at the very least, to say something about the art.

Tai Mitsuji

RULE SIX: Don’t ask the artist to justify the work because you don’t get it.

A golden rule of appreciating art is if you have to ask the artist what it means then the work of art just isn’t working. Regardless of who you are, be you a hapless layperson, a semi educated University graduate, or some highfalutin’ art world dilettante, it’s all the same. A work of art has to involve the viewer, and so what you are experiencing is what the artwork is about.

While a lot of artists like to have an artist’s statement (about what the artwork means or where it came from), if it isn’t evident or obvious in the work itself, then there’s a very high chance that is not what the work really means.

Another golden rule is that context is everything, and so whatever the artist may have intended is just a bonus. So rather than asking an artist to justify their work because you don’t understand it, a more fruitful approach is to start by telling the artist what you think it might mean. Remember: there’s no wrong answer.

Andrew Frost

RULE SEVEN: Don’t pretend to know someone’s work when you don’t

There is one phrase that you never hear uttered at exhibition: “I don’t know their work”. One of the art world’s most practiced fictions is that everyone seems to know of everyone… and that not knowing is some kind of cardinal sin. There is, dare I say it, cultural capital in this presumed knowledge. Someone mentions an artist and rather than simply asking who they are or what they do, you find yourself nodding knowingly, or brazenly uttering something like “Ah yes, I love their earlier work from 1990s”.

This hollow practice will sustain you through a wide spread of uninformed and face-saving conversations, with one exception: when you find yourself speaking to the artist, themself.

A word of advice, this is not the time to pretend. It’s fine not to know! Picture the night- marish alternative. Some vague memory prompts you to start talking about how much you enjoy their oil painting, only for them to reply that their practice is entirely dance- and movement-based. No one wants that. Resist your every instinct and admit what you do not know. Because following this confession, you actually get to engage their work. Maybe you like it. Maybe you don’t. Maybe it’s the worst thing you’ve ever laid your eyes upon. At least, you know.

Tai Mitsuji

RULE EIGHT: Don’t ask for discounts

It’s incredibly hard not to look cheap when you ask for a discount. A work of art is nearly always bespoke, a one of a kind, and artists and their galleries ask for a particular price because the artwork is a premium object. So, when you think about the fact that a gallery-represented artist usually only gets shown once every 18 months to two years, asking them to shave off a few hundred or a thousand dollars is like asking them whether it’s okay their children get no Christmas presents this year.

Artists are represented commercially because they are leaving the sticky business of deciding on a price to their professional representatives. Making an end run around a gallerist to their artist for a discount puts everyone in an incredibly embarrassing position, and what’s more, it can lead to huge complications down the road if the artist agrees to a studio door sale without their gallerist’s knowledge. And asking an artist who is self-represented for a discount is an even bigger no-no. The asking price doesn’t even begin to cover the number of hours that went into making it, the costs of production, transportation, presentation and so on. So don’t even contemplate asking an artist to knock off a few hundred bucks. C’mon, you don’t want to look cheap.

Andrew Frost

RULE NINE: Don’t ask about the inspiration

As a high-level concept, artistic inspiration refers to the mysterious internal process by which the great makers of culture come to create something out of nothing; those unconscious forces that act upon an artist to mark a blank canvas or page with their special kind of genius.

Throughout human history, the speculated source of this inspiration has ranged from the divine to the innate biological structure of the human mind.

While the question of artistic inspiration is one of the enduring philosophical questions about human nature, try to avoid posing it in order to fill the silence between you and artist when you’re standing in front of their work. Asking about what inspires them can make artists feel the need to have to justify what they do, and this will be tedious for you and embarrassing for the artist.

Best case scenario is that they will fall into romantic cliché, telling you that they are “inspired by nature” or “inspired by the female form”, or even more desperately, “inspired by the female forms I see in nature”. Worst case is when they feel the need to justify what they do on an ontological level: “I don’t make art; art makes me” or “I’m just a vessel for whatever shows up when I walk into my studio”.

Carrie Miller

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 95, January to March 2021.