Sign Me Up: The Unexpected Pleasures of an Art Buying Collective

Sometimes, we don’t just see the art on our walls, but also the story within it.

Words: Duro Jovicic

Human experience, at its core, is predicated on forming and being part of groups – religion, nationality, political ideology, employment, hobbies – where likeminded people, in the spirit of cooperation, can achieve goals that would otherwise be out of reach. The purpose and attraction of art buying as part of a group is to build an art collection, learn about art and have the experience of living with art on your walls. Fran Clark, director of ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne who has been overseeing art collectives for decades, likens it to “drinking exceptional wine. Once you’ve experienced the best, you acquire the taste, you can identify it and your visual palate can’t reverse it, and asks for more. Also, seeing a piece for a short time in a museum or gallery space as compared to living with it at home makes a huge difference.”

After finishing a Fine Arts degree at the University of Queensland, Kirsten Butera worked as a gallery assistant at Milburn Gallery and then at Niagara Gallery for Bill Nuttall, who advised on art-buying collectives, planting the seed for her to begin one with friends. Butera went on to deftly spearhead the formation of two art-buying collectives, the first called Acht (eight, in German, signifying its member count) and the second, of which I am part, called Finch (influenced by the book Goldfinch by Donna Tartt). Butera says, “the initial appeal was in pooling resources to purchase pieces that were out of reach for just one person.… it allows you to take more risks as it’s not a case of ‘I have to love this painting forever, or this sculpture, or this photographic work’ as it will be moved on after six months.” This development is hardly a surprise for someone who, on her engagement, by her now husband Frank, went for a Kevin Lincoln painting over a ring.

For Butera’s groups, a legally binding document specifies the voting structure for art purchases, and annual contributions, along with a mandate of supporting Australian contemporary artists through the gallery system, and an agreement on how to wind up the collective, if desired, at the ten-year mark. Clark gave a firm “no” when asked about any tensions in the collectives she’s been involved with. Lawyers draw up the terms, and conditions are agreed upon. There are even contingencies in place in case someone dies. “Has it happened?” I ask. It has. The equity share was sold to another individual wanting to be part of the collective.

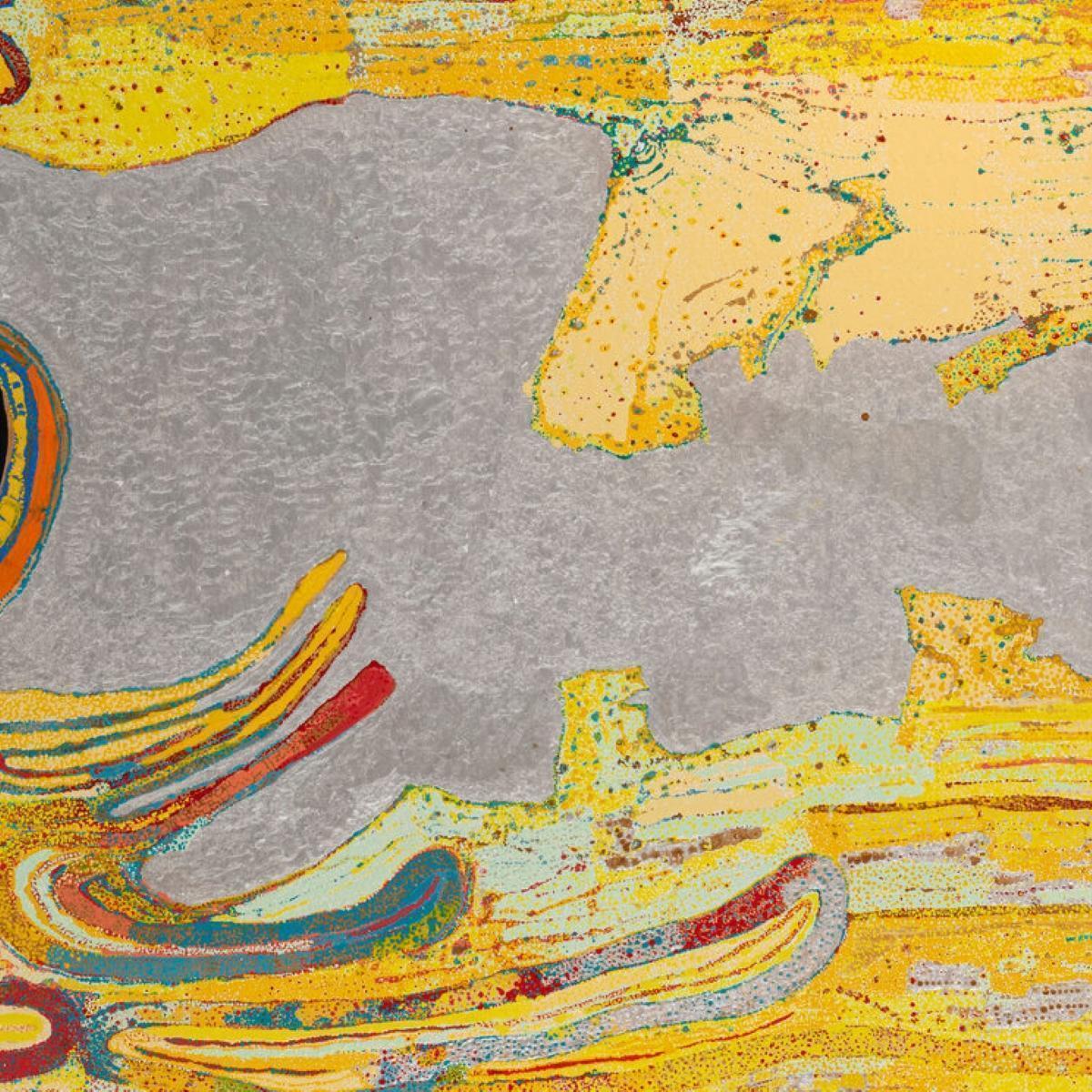

On occasion, Butera’s collectives miss out on art purchases due to slow responses, and rarely do all members get together for organised art-viewing days; there’s an understanding that people lead busy lives, and a loss one day is an opportunity the next. Intriguingly, investment is only ever broached as something to steer away from. The idea is to put an artwork up for a vote that moves you and if, in time, it appreciates in value, so be it. The hang is a recurrent theme with Finch member Liz Abbott, who speaks of the pleasant surprise of, “when you hang a work at home that you didn’t vote for or that wasn’t a real favourite for you but suddenly comes to life for you.” Such surprises are it seems, part of the art appreciation journey – surrendering your fate to the decision of a majority. As a Finch member myself, I wasn’t overly enamoured by Serpentina II by Petrina Hicks. But when the time came for the biannual artwork rotation, I’d developed a deep affection for it and mourned its departure. The 2019/20 National Gallery of Victoria survey exhibition of her works used Serpentina II as its main advertising image, bolstering its appeal.

The social aspect, coupled with organised exhibition viewings and studio/stockroom visits, heightens the enjoyment, with many collective members becoming deeply invested in the artists. A visit to Hobart’s Bett Gallery, where staff were exceedingly generous with their time and knowledge, saw Finch purchase Not Angry by Lucienne Rickard. Meeting Rickard, while she was installing her work for the show, and hearing stories of how she occasionally needed to pause painting – as her instrument of choice, her finger as opposed to a paintbrush, had blistered, and needed to heal – enhances the piece with a personal connection. Sometimes, we don’t just see the art on our walls, but also the story within it.

For those interested in forming an art collective who are daunted by the prospect, or feel they don’t have the numbers, guidance is available from art galleries – Bett Gallery provides the option of joining a collective with clearly stipulated expectations, to provide ease of mind. This legacy stems from its founder, the late Dick Bett, who was one of the first people to drive the creation of art buying collectives in Australia. Playing to your groups’ strengths also helps allow for a collective to hum along. One Acht member is a lawyer, providing the framework for the agreed-upon establishment guidelines for both collectives, while another is proficient in excel, executing how and when pieces circulate.

Acht persevered for 20 years, weathering moves by members interstate and overseas, separations, divorces, births, and periodic lapses in communication. Its members became lifelong devotees and proud owners of emerging and mid-career Australian art. Acht ceased annual fee collections for purchasing art at the 12-year mark though formally dispersed with its works at year 20. The artists that commanded stellar prices, such as the Juan Ford and Michael Zavros paintings, were auctioned off in secondary markets, and the monies reinvested into the collective. This allowed Acht members’ funds to individually purchase the remaining artworks owned by the collective via an internal auction. Fierce bidding ensued; a clear indication of how attached people were to certain works. A modestly sized Julia Ciccarone painting even reached a commendable five-digit figure.

There have been murmurings of wrapping the collective Finch up at the 10-year mark which Butera is open to. I wonder how people, once confronted with such an impending deadline, will feel about pulling the pin on this journey – one which Butera readily admits has seen her maintain fond friendships across borders that may have otherwise faded away. Former Acht member, Andrea Matthews, sums up the pleasures of membership: “There’s no end of cool stories. Pieces we got, pieces we missed out on, artists that are now famous, art that went up in price, art that came down in price. Weekends away together, going to galleries and drinking too much wine!”

Do you have a burning question about the way the artworld operates? Send it to feedback@artcollector.net.au

Image: Petrina Hicks, Serpentina II, 2015. Pigment print, edition of 4 + AP, 115 x 115 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Michael Reid, Sydney.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 104, April to June 2023.