Ali Tahayori: Queer Light

Ali Tahayori finds safety in darkness. It’s curious, then, that his work relies on light.

Words: Rose of Sharon Leake

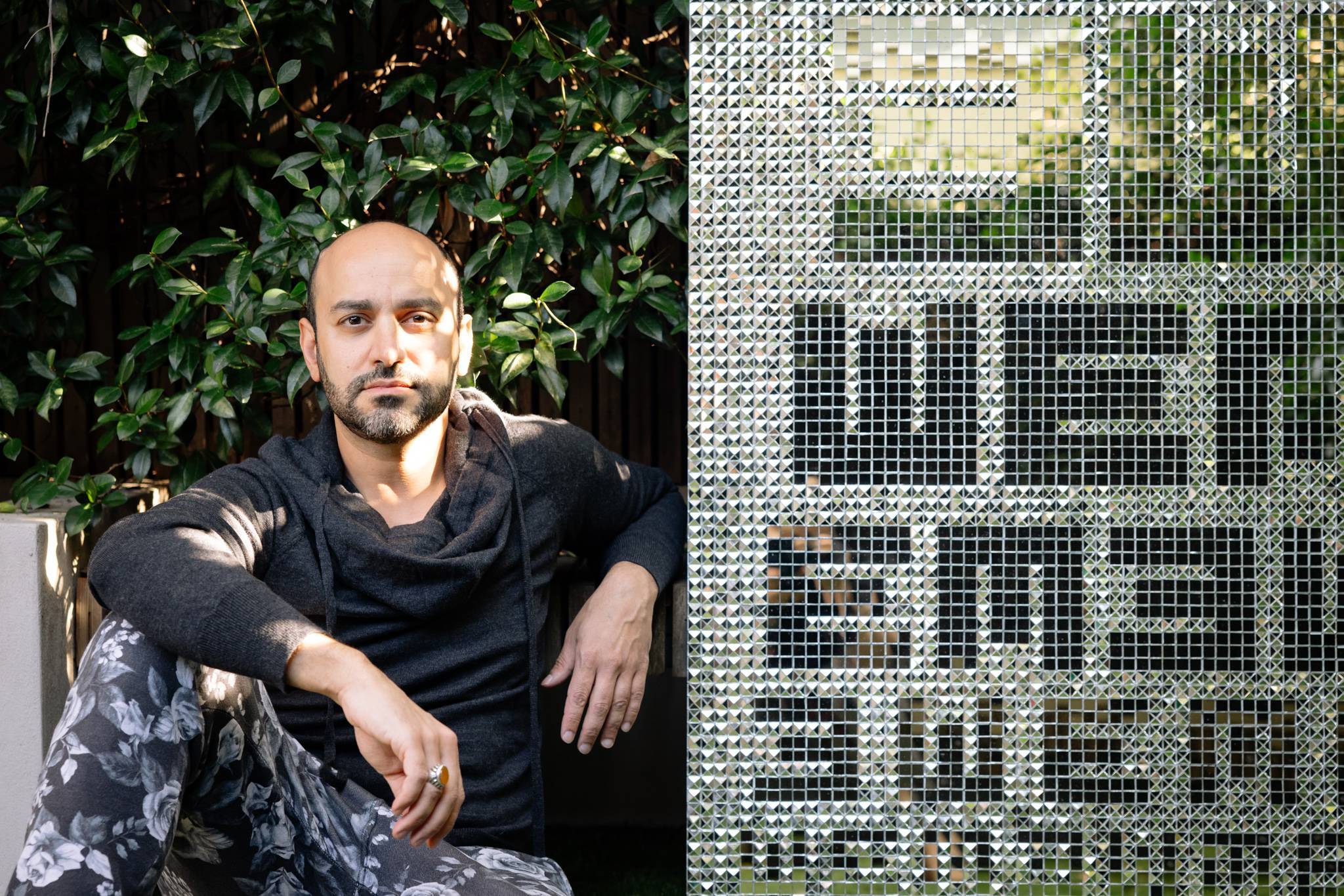

Photography: Jacquie Manning

“I love images. I’m obsessed with them,” Ali Tahayori tells me. His obsession with the politics of images and the way they reveal untold histories runs far deeper than I could have imagined; it traverses continents, politics, culture and identity. As I speak with him over the phone, I am increasingly aware of the pain, sadness and trauma ever-present in Tahayori’s life, yet hope, beauty and resilience also filter through the phone line; that is the power of his story. Born in 1980 in Iran, the Sydney-based artist fled his home country in 2007, searching for safer soil. “I am a child of a revolution, there was so much trauma and conflict that continues today,” he says. “The first eight years of my childhood were spent running from one shelter to another. The war finished when I was eight or nine. Then the consequences came through. My life experience as an Iranian gay kid during a war and in the homophobic environment of Iran [means that] pain is so much part of my everyday experience. Then moving to Australia I thought I had found heaven, [only to feel] like a stranger again.”

While his practice explores the idea of light, reflection, and image-making, Tahayori’s initial interest in darkness is what I find most interesting. “When I was a child I was always drawn to dark places,” he tells me. “The darkness was a place to hide. These places gave me comfort and safety. When I went to the cinema, the darkness enabled me to be myself, I could be anyone.” Tahayori’s studies in photography through a Master of Fine Arts in Photomedia from Sydney’s National Art School continued his yearning for somewhere to be himself; the photography studio’s dark room liberating him from the confines of his own identity within society.

He tells me of his first intimate experience in Iran as a young man: a public toilet in a basement; dark and secluded, a “romantic and beautiful” experience Tahayori recalls. Not able to return to Iran to visit this place, Tahayori asked a friend to take photographs of the space as it is now. These images, along with the emotions and memories Tahayori experienced recalling this place, formed the basis for his work Impossible Desire, a video installation work depicting a series of photographs being painted by Tahayori using his own bodily fluids. While such arresting video works are a key part of his practice, it is his fragmented mirror works he has become recognised for (Tahayori was recently added to THIS IS NO FANTASY’s stable in Melbourne; he won the Prix Yves Hernot Photography Award, National Art School, Sydney 2022; and featured in Photo London 2023).

At this point in our conversation Tahayori instructs me to Google the Shāh Chérāgh, a mosque in his birthplace of Shiraz, Iran. Up pop images of the interior of a building elaborately encrusted in broken mirror fragments; it looks almost contemporary despite its age. “The moment you step into this shrine you feel touched by light, you feel the tactility of light, its refractions and reflections,” says Tahayori. “Āine-Kāri (meaning mirror works) was a craft developed in Iran in the 16th and 17th century. When mirrors arrived from Europe, they often came broken so Iranian artists used this to their advantage to make artworks for mosques and mausoleums.” Building this idea into his practice, Tahayori sees mirrors as a challenge to the notion of representation. “Photos are fixed, they are two dimensional and capture a moment in time in the past. Whereas mirror images are dynamic and contingent to time and space. In my practice I’m really interested in bringing that tension to the surface between photographic image and mirror image.”

The fluidity that these fractured mirror works enable speaks also to Tahayori’s queer self. “Queerness for me is not a form of identity,” he tells me. “It is not restricted to gender identity or sexual orientation. It is more a state of being. It is one that resists definition and labelling.” Tahayori talks of his new triptych work Geometry of Belonging showing in a solo show Looking at Me Looking at You with THIS IS NO FANTASY in August. A self portrait, the work depicts Tahayori’s bare torso with his face obscured by fragments of mirror. As you stand before it, any hopes of otherising the subject are dismantled as our own reflection looks back. With this work, and his practice as a whole, Tahayori questions the idea of being seen and the complexity of identity, particularly a politicised identity. “My work definitely has a political message. I believe that message goes beyond the boundaries of Australia. I like my work to question rather than give possible answers. [My work] requires time from the audience. Not to change their political views but to change the way that they see life, pain, and other humans.” While burdened with an upbringing tainted by trauma, pain and sacrifice, ultimately, Tahayori wants to foster an environment he was denied through his upbringing. “I want queer bodies to feel safe [around my work],” he says, “free and liberated to express themselves however they want. I want to create a space for meditation, imagination and reflection.”

DIANNE TANZER & NICOLA STEIN – Directors, THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne:

“Art has incredible power to shape discourse and inspire social change and we were drawn to the ways in which Ali Tahayori’s practice embraces this, combining both the political and the personal. His work unpicks complex themes of displacement, otherness, identity and belonging. It does this in a nuanced and sophisticated way, often with an erotic and subversive undertone. These themes are particularly timely and relevant in the diverse and evolving landscape that is Australia.

“Tahayori’s work is attracting strong institutional and collector interest. Although he only completed his Master of Fine Art at the National Art School, Sydney in 2022, he is on an exceptional career trajectory.

“He was winner of the Prix Yves Hernot Photography Award, National Art School, Sydney 2022; highly commended, Gosford Art Prize 2022; winner of Smith and Singer People’s Choice Award, Bowness Photography Prize 2021. Tahayori was a recent finalist in Vantage Point Sharjah 10, UAE, Hornsby Art Prize and Blacktown Art Prize.

“In 2023 Tahayori has been honoured with a solo show at Gosford Regional Gallery, featured in Photo London, curated by Roya Khadjavi Projects, New York, and included in Braving Time: Queer Contemporary, Sydney World Pride, NAS Sydney.

“The mix of aesthetically arresting, technically skilled and thematically complex is what makes Tahayori’s work so compelling. We think collectors viewing this art will see it as privileged access, allowing them to explore Tahayori’s world through a different, multifaceted lens. In particular, collectors may recognise something beyond ordinary explanation taking them on a type of spiritual quest. His works are priced from $4,500 upwards.”

TAI MITSUJI – Art critic and curator:

“I first came across Ali Tahayori’s work at an exhibition at the National Art School: Braving Time: Contemporary Art in Queer Australia. I had been commissioned to write a short review of the show. To my mind, it was too short. The article’s length asked for more than an economy of prose – it demanded an almost violent distillation of the show. It was a problem. So, when I sat down to begin writing, I asked myself a simple question: what artwork spoke to me? What piece still played on my mind and whispered at the edge of my thoughts? The answer was Ali’s.

“In Ali’s work, concept and form elide, and collapse into one another. Or put another way, I always have the unmistakable feeling with his work that the physical object is not carrying an idea. Rather, the idea has become the very thing itself. To me, this is where his quiet brilliance resides. Across both his photographic practice, and his Āine-Kāri (mirrorworks), Ali creates works that complicate the very idea of sight and the way that we see the world.

“Much of Ali’s work is concerned with the idea of outsider-ness. It is a somewhat unsurprising concern for the artist, who had to contend with the homophobic climate of 1980s Iran and migrated to Australia in 2007. The pressures of queerness, displacement, and diaspora all flow through his work. Yet the simple fact of this biography is not what makes his work compelling. Rather, it is the way in which Ali’s art is able to suture together personal experience with form, arresting our gaze as he animates our mind.”

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 105, July-September 2023.