Zina Swanson: Out of the Woods

Historic plant lore has given Zina Swanson a contemporary way to consider how we make sense of the world around us.

Words: Chloe Lane

Geraniums growing in an open window will prevent flies from entering the room. Burn wood, and the flames will form themselves into the shapes of the leaves of the trees from which the wood came. Any plant thought of too much will not thrive. These examples of curious plant-related lore each provide the basis for a painting in Zina Swanson’s forthcoming solo exhibition at Sumer, Tauranga.

“I’m interested in how we force histories onto plants as a way to understand them,” Swanson says. Her most recent work makes use of oral histories to interrogate the way we live with plants. The result is a collection of immaculately rendered watercolour and acrylic paintings that are humorous and uncanny while also hinting at a darker view of humanity’s relationship to the natural world.

In Tiger lily with nose border (smelling tiger lilies causes freckles) (2020) two walls of freckled noses appear to close in on a blooming tiger lily. It’s odd, amusing – Swanson often uses repetition to this end. Though take a step back from the work, and the noses collectively could be mistaken for less a flower-friendly beehive than a pair of menacing wasp nests. Swanson wants her viewer to laugh, but she also aims to unsettle.

The saying that this painting illustrates is taken from Animal and Plant Lore (1899), a collection of oral English language histories. Plant lore, which has no scientific founding, has given Swanson a fresh way to consider how we make sense of the world around us. She also has an ongoing interest in Tompkins and Bird’s infamous The Secret Life of Plants (1973) that makes pseudoscientific claims about plant sentience. Oak blush (2019), a quietly disarming watercolour of bespectacled eyes draped in oak leaves, was created in response to an excerpt from this book. It is now held in the collection of the Wallace Arts Trust.

“Swanson, now an early mid-career artist, appears something of a quiet achiever,” says Dan du Bern, director at Sumer. “She has been the recipient of a number of New Zealand’s highest accolades for young artists.”

While much of the interest in her work to date has been centred on New Zealand’s South Island, Swanson has exhibited extensively with solo and group presentations at most of New Zealand’s top galleries and museums. These include the Christchurch Art Gallery, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, City Gallery Wellington and Artspace Aotearoa. Her works are held in the collections of Christchurch Art Gallery, Dunedin Public Art Gallery and The Dowse Art Museum, and she has been the recipient of the prestigious Frances Hodgkins Fellowship. She is represented by Sumer in Tauranga and Jonathan Smart Gallery in Christchurch.

“The very nature of her work – its modest scale, the everydayness of her subject, her slanted surrealism – does not scream for attention in the way some of her Northern counterparts’ works do,” says du Bern. “And yet, for those who are opportune enough to encounter Swanson’s work, there is something compelling and enthralling about it which invariably holds the viewer.”

Swanson’s paintings always have a human presence – the outline of a face, a nose, a hand – or something that suggests a human has been here: a window, neatly arranged sticks. Yes, these works are smaller in scale, but this is one of their strengths. They’re scaled for an interaction with the viewer that is personal, intimate.

The visual pleasure of Swanson’s use of repetition is undeniable. In Forget me not (2019) a silhouette of a head is composed of many pressed forget me not flowers. “Each flower head was carefully removed,” Swanson says of the work. “I did this using a pair of very fine tweezers. I initially thought it would just be an outline, but as I proceeded the image grew to be nearly completely filled in.” She describes these time-consuming almost obsessive processes as a “sort of contradiction, in that it can be a stressful way to make work but also somewhat meditative.”

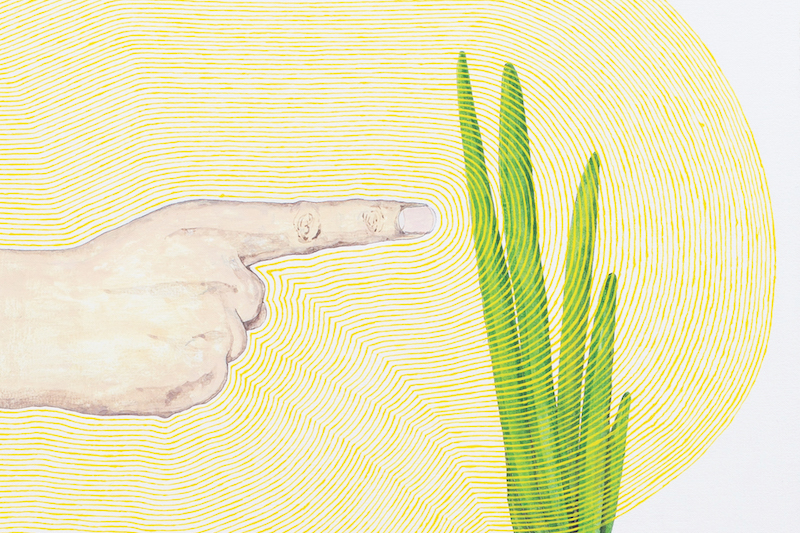

Swanson has recently shifted from making works on paper to works on canvas. Watercolour has long been a favourite medium, though most of the paintings in the Sumer show are acrylic. Stunt (pointing at a daffodil will keep it from blooming) (2020) is a stunning example of Swanson’s control. A hand reaches into the frame of the painting, index finger extended. The image has a The Creation of Adam energy to it, though this hand could belong to any mortal person, and it’s trying to stop this plant from blooming. The fine yellow lines that radiate around the extended finger both shield the hand and smother the plant. The title encourages the viewer to contemplate this futile task. Though considering this work in 2020, this determination to bend the natural world to our will also resonates on a deeper, darker level.

Featured image: Zina Swanson, Stunt (pointing at a Daffodil will keep it from blooming), (detail), 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 35 x 25cm. Courtesy: the artist and Sumer, Tauranga.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 94, October – December 2020.