Behind the Scenes: The white idea

Might we be seeing the beginning of the end of the white cube?

Words: Tai Mitsuji

When I think about the “white cube,” I don’t think about its history. My mind does not automatically cast itself back to the newly introduced curatorial strategies of MoMA and Alfred H. Barr Jr. in the 1930s. Nor, if I’m being honest, do my thoughts dwell on Irish art critic Brian O’Doherty’s seminal essays from the 1970s, in which he first coined the term white cube to describe the minimalistic, colourless, space that has come to dominate our galleries and museums. Even today, it is hard to think about these white walls, which feel slippery and elusive despite their ubiquity. These walls are at once commonplace and yet invisible. The pervasiveness of the white cube means that its aesthetic often seems like something of a foregone conclusion, rather than a conscious choice. But, of course, these blank walls do have a history, and are a choice.

In 1976, in a series of critical essays published in Artforum, O’Doherty donated a name to the phenomenon of stark walls and sparse curation: the white cube. For O’Doherty, this space was hermetically sealed. It was something akin to a religious sanctuary that remained insulated from the concerns of the secular world. Moreover, it was a kind of eternal space that existed almost beyond the physical realm. “The outside world must not come in, so windows are usually sealed off. Walls are painted white,” O’Doherty wrote. “Their ungrubby surfaces are untouched by time and its vicissitudes.”

Yet, if the secular world did migrate into the space, it was transformed. In O’Doherty’s white cube, the standing ashtray suddenly became a sacred object, while the fire extinguisher on the wall mutated into a sculpture.

Put simply, the everyday became art-ified. But of course, you know what he’s talking about! Everyone has experienced that moment when you go to sit on a bench in a museum, and just as you are lowering yourself down, you wonder whether the seat is a convenient resting place, or priceless artefact from the Bauhaus. The agitation of the security guard usually indicates which conclusion is correct.

Despite the passing of decades and changing of the institutional guard, the transformative power of the white cube has endured. Indeed, O’Doherty’s old sentiments were perfectly captured in two scenes from the 2017 film The Square, which presented a brilliant satire of the art world in all of its glory and perversity. In the first scene, a cleaner carefully manoeuvred an industrial sweeper around piles of gravel that sat at equidistant intervals in the white cube. For the dramatists, this was Chekhov’s Gun on the wall – the thing that hung innocuously in plain sight in act I, only to be inevitably fired in act II. By the time we reached the second scene, the proverbial pistol had gone off: two anxious curators talked in hushed yet furious tones about the artwork, which had been vacuumed away. Here, the strangeness of the white cube was on full display, as dirt and detritus could no longer be cleaned.

Looking at the white cube today, my concerns are not so theoretical. They arise out of the experience of visiting different cities yet walking through the same gallery. Indeed, I somewhat unexpectedly find myself in the same camp as uber-collector Charles Saatchi, who in 2003 declared that “after years of showing art floating in pristine arctic isolation, it’s a revelation to break out of the white cube time warp. If art can’t look good outside the antiseptic gallery spaces dictated by museum fashion of the last 25 years, then it condemns itself to a worryingly limited lifespan.” Galleries should not feel like operating rooms – sterilised and sealed off from the contaminants of the world outside – yet, so often, they do.

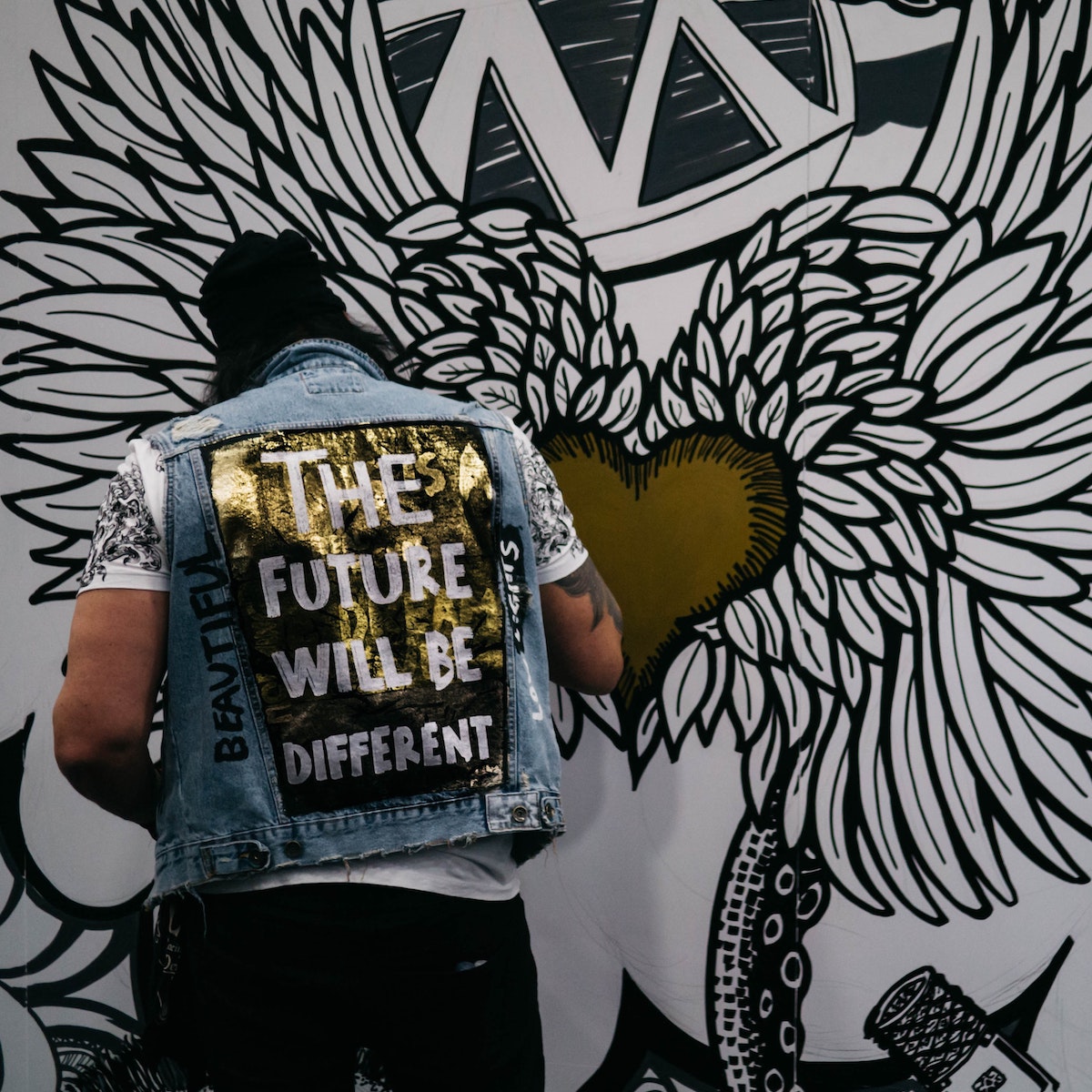

It is not that the white cube is so terrible. Rather, it is that when you step into an exhibition that disrupts this white uniformity – recall Tom Polo’s impactful I still thought you were looking (2019) at Sydney’s Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery – that you suddenly realise what you’ve been missing; what you’ve unconsciously been yearning for. Colour. Life. Mess. Some trace of the fumbling human hand, rather than the precision of the surgeon’s scalpel. Anything but the tired perfection of the white cube.

Photo courtesy: Unsplash.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 97, July to September 2021.