Cool Hunter Predictions: Min Wong

Min Wong’s artwork explores the commodification of spirituality through an expanded sculptural practice.

Words: Josephine Skinner

It might seem a no-brainer to predict that Min Wong’s profile might accelerate after two years of lockdowns that popularised self-care, caused a resurgence of self-improvement, and incited the new zeitgeist of taking time to reflect on what is really meaningful.

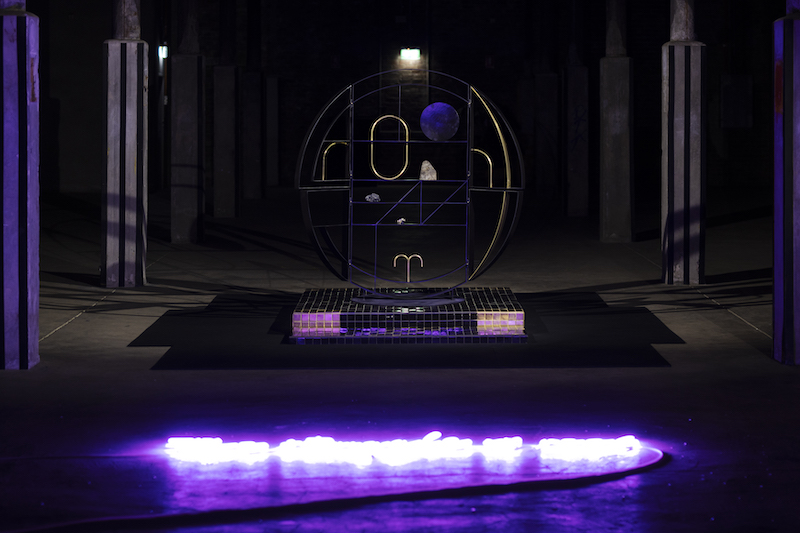

Wong’s artwork explores the commodification of spirituality and her expanded sculptural practice incorporates a medley of references, mirroring the smorgasbord of spiritual modalities, esoteric ephemera and wellness products and regimes that are widely available to consume. Mocking the new spiritual lifestyle, Wong merges mystical and branding iconographies in minimal graphic shapes that are digitally printed onto fabric and sculpted into refined brass and steel forms. These fabrications become spiritual décor that showcase house plants and collected esoterica, including crystals and books on spiritual teachings, along with affirmations emblazoned in neon.

If the significance of Wong’s import is a no-brainer, however, it’s not because her work illustrates a renewed spiritual turn in the popular milieu, but rather, offers a critical lens and much-needed historical contextualisation of the spiritual self. Through appropriation, hybridisation and reconfiguration, her works connect contemporary spirituality back to 20th century reinterpretations of eastern philosophies. From the counterculture movement in the 1960s and 70s, to New Age spirituality in the 80s and rise of self-help gurus in the 90s, Wong’s work crystallizes how once radicalised self-seeking has been absorbed by a self centering neoliberal world, epitomised by the now booming wellness industry.

Crucially, Wong’s work values the human desire to seek authenticity, meaning and connection as much as it critiques the culture that commodifies these things without delivering. Her own personal relationship to spirituality is layered and sincere. In a counterbid to the mainstream’s co-option of spirituality, she creates space for a heightened awareness of commodification and consciousness, inciting critical thought as an avenue for renewed connection with self, community and nature.

In 2020, her intimate exhibition Inner Workout at Sydney’s Artspace Ideas Platform opened quietly, on the tail end of the first NSW lockdown. Her 2021 exhibition, Purple Haze at Carriageworks’ Clothing Store (where she was a resident artist), was markedly ambitious and expansive, yet opened to an absent audience during the week the second lockdown began. Bathed in purple light – a colour associated with pure consciousness, wealth and devotion – Purple Haze integrated Wong’s formative spiritual influences; holding the memory of her mother, an Evangelist, and interspersed with plants that were her father’s, a Taoist. Wong pursued her own spiritual path through a devotion to Bikram yoga, a practice led by a now-disgraced guru. This personal ambivalence is perhaps inferred by the centerpiece; an altar-like form incorporating aspects of her horoscope and dramatically staged to evoke both enlightenment and extravagance. It is the imperceivable line between sceptic and believer that makes Wong and her work simultaneously relatable and ultimately, somewhat mystically, indecipherable.

In 2022 Wong’s career is set to reach new levels of exposure. Her most ambitious presentation to date will be featured in the Adelaide Biennale, where she’ll create an immersive environment exploring elements of interactivity. Also in 2022, she will produce a new site-specific commission at Sydney’s Cement Fondu alongside esteemed US-based artist Shana Moulton and Adelaide’s Hugo Michell Gallery will stage a solo show of her work in April. With these pivotal opportunities for Wong, it is an exciting time to become a follower of her work.

Featured image: Min Wong, Purple Haze, 2021. Installation view at the Clothing Store, Carriageworks, Sydney, dimensions variable. Photo: Kuba Dorabialski. Courtesy: the artist and Hugo Michell Gallery, Adelaide.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 99, January-March 2022.