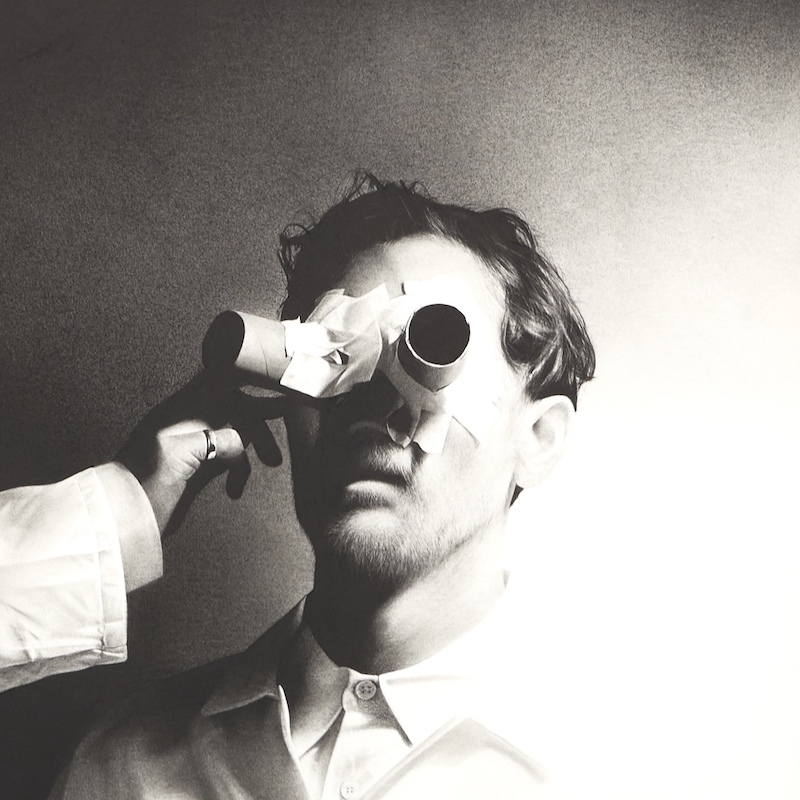

Cultural Capital: And Then I Realised…

Getting to the place where you’re on good terms with contemporary art involved a journey sometimes

you forget you took. The stopovers along the way were a series of realisations. Let’s revisit them.

Words: Andrew Frost, Carrie Miller, Micheal Do

Illustrations: Coen Young

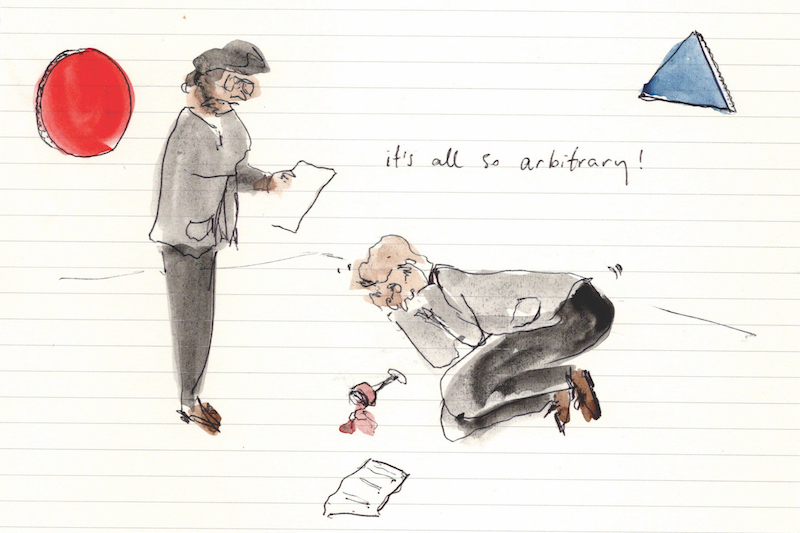

REALISATION ONE: Not being able to understand a work of contemporary art straight away doesn’t make me stupid.

The first stop on the contemporary art collector’s journey to self-actualisation is to learn to cope with that nagging sense they are the only person in the room who’s stumped by what they’re looking at. Over time, collectors know that the art world is full of people secretly thinking they are the only one baffled by contemporary art, and that’s why so many pull the Thinker pose when contemplating it. Eventually, serious collectors even come to appreciate the uncomfortability associated with not getting a work straight away – they read it as a sign that the art has something to say, it’s just saying it in a new language that’s still foreign to them. This is why it’s important for people new to the collecting game to avoid falling into the reactionary trap of rejecting the art before it rejects you. Until you gain some credibility in the artworld, it’s wise to keep your opinions about what you considered rubbish on the lowdown.

Carrie Miller

REALISATION TWO: What I’m looking at isn’t a representation of all contemporary art.

When collectors begin acquiring work, they will be tempted to believe there is a strict orthodoxy as to what counts as contemporary art. This is understandable when the artworld itself seems to gatekeep what’s considered genuinely contemporary. If a collector enters this world at a cultural moment when video art is the thing, it will be easy for them to think that all representational painting is of the past and can be no more than mere nostalgia with nothing modern to say. The more work they see, however, the less homogenous contemporary art as a cultural category becomes. In fact, they will realise that trying to define contemporary art is like trying nail jelly to a wall. And nailing jelly to a wall may just be a form of contemporary art. This revelation allows collectors to relax a bit. If what they’re looking at doesn’t resonates with them, that’s ok. In a postmodern art world, there’s something for everyone, as long as they’re prepared to defend their tastes (especially if it’s representational painting).

Carrie Miller

REALISATION THREE: Everyone is still figuring out if contemporary art is good or bad (and this will actually take decades).

Any collector who sets out to gather works that are only considered to be “good” in their time is surely in for a rude shock. In a few short years, maybe in a decade or two, what is considered “good” may by then be considered to be “bad”. What is contemporary and what is art are an ever-evolving set of received ideas and figuring out whether it’s good or not good is a cultural process of evaluation and re-evaluation, framed by a set of changing attitudes, social mores and a shifting political consciousness. This can mean art that merely falls out of fashion, or wasn’t that great in the first place – more sort of acceptable – or was so ahead of its time that it sits outside of the current fashion. Sometimes great art is only understood in retrospect, while other art surfs the zeitgeist like a thrill ride. The thing is, it doesn’t matter. It’s the journey that counts.

Andrew Frost

REALISATION FOUR: Artists aren’t a special kind of person… they are just as capable of being as stupid and annoying as real estate agents.

We like to think that artists are a special kind of person; more sensitive, more tuned into the Zeitgeist, equipped with an almost God-like capacity to reveal the innate truths of human existence. Art collectors especially need to believe this – why else would you drop big wads of cash on a sculpture made of chip packets? The more collectors knock around the artworld, however, the more they come to realise that artists are just like the rest of us. They are susceptible to the same pressures to become successful, to fill that gaping spiritual hole at the core of themselves with external validation and expensive wine. It can take art collectors a long time to come to this realisation, and that’s both a good and a bad thing. Good, because bumping artists off their cultural pedestals allows collectors to demystify artmaking, enabling them to make less romantic decisions about what to collect. Bad, because this process of demystification can make that sculpture made of chip packets look like something the next-door neighbour’s kid could do.

Carrie Miller

REALISATION FIVE: “All profoundly original art looks ugly at first”.

As influential art critic Clement Greenberg put it. It makes logical sense that a genuinely original work of art must seem repugnant on first reveal. By its very definition, avant-garde work is necessarily provocative to the physical and moral eye. The extent of the novice collector’s exposure to art is often limited to mainstream museum exhibitions, so this shock of newness can be profound. But with experience, they will understand that the paintings in those blockbuster shows that end up as prints on the wall of their local dentist were once as offensive as the video of angry, drunk clowns fighting that they are now watching. While this is an important realisation for the aspiring collector, mature collectors also know not to hold Greenberg’s dictum too tightly. They’re aware that the anti-aesthetic impulses of much contemporary art can simply be a performance of genius, and will be able to discern the difference between art that is genuinely original and derivative work that conceals its conceptual banality by cloaking it in in provocative packaging.

Carrie Miller

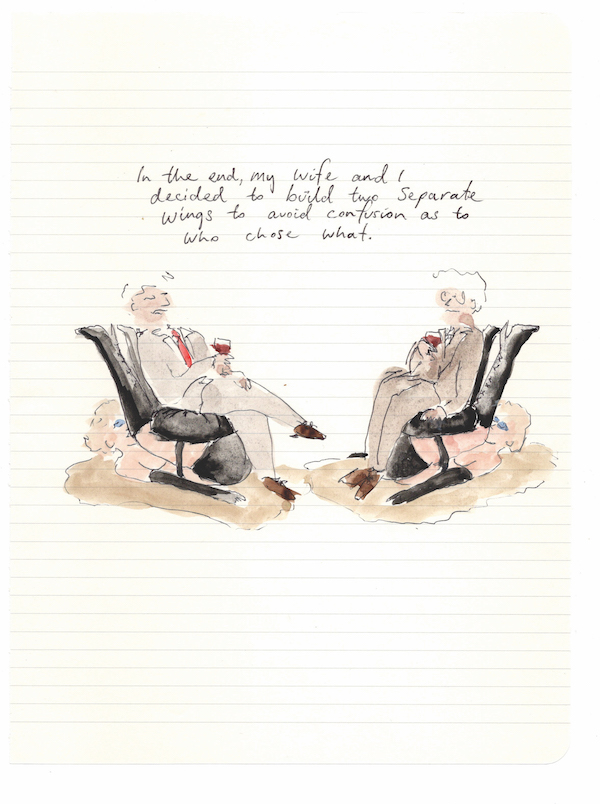

REALISATION SIX: Good taste is not a consensus. When was the last time you checked with your friends, peers or colleagues before you decided to buy a work of art? Sure, you might gauge a sense of what other people are thinking, feeling, or reacting to, but how often do you decide not to do something based on the opinions of others? The sensible answer to these questions is: sometimes, or maybe even better: never. When taste is decided by consensus, art becomes bland, boring and repetitive. Art that takes chances, and your willingness to engage with it, is the result of education, scholarship and a dedication to finding out more. The well-rounded collection is something that recognises quality and execution. The more you put yourself into the collection – the idiosyncratic you that makes you different – are the things that will make your selection valued, and valuable.

Andrew Frost

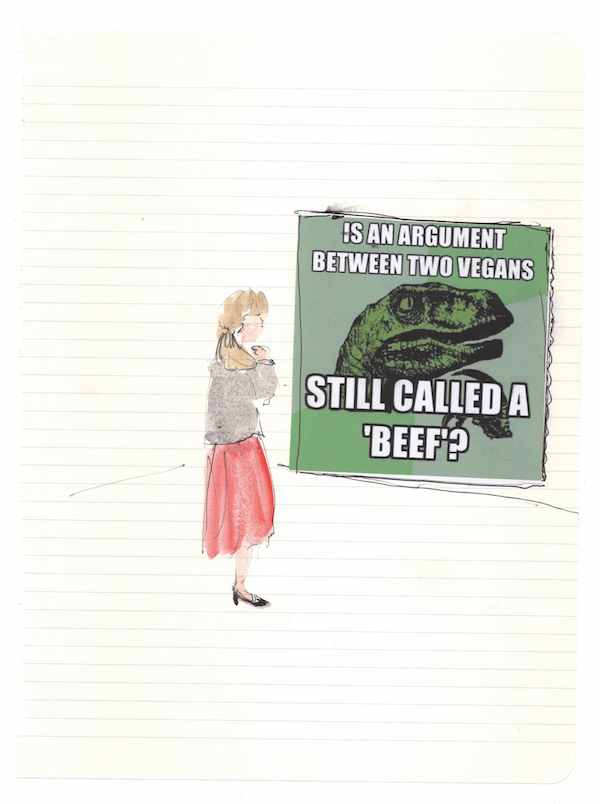

REALISATION SEVEN: Good art and the art that I like don’t have to be the same thing.

Good art tends to strike when we’re least expecting it. Only when we finally encounter great work, do we then realise it was missing from our lives. This is the nature of art appreciation. Despite this feelgood power, enjoying art can be tinged with guilt, when we appreciate art that we think we shouldn’t; whether it is judged as bad taste, passé, lacks criticality, or just plain trivial. While a little bit of scepticism in art appreciation goes a long way, “good art” sanctioned by the right art world actors like critics, curators and galleries doesn’t need to be the art you actually enjoy. The vagaries of taste will change – that’s a given – but the meaningfulness of any artwork is personal and that can’t be excused.

Micheal Do

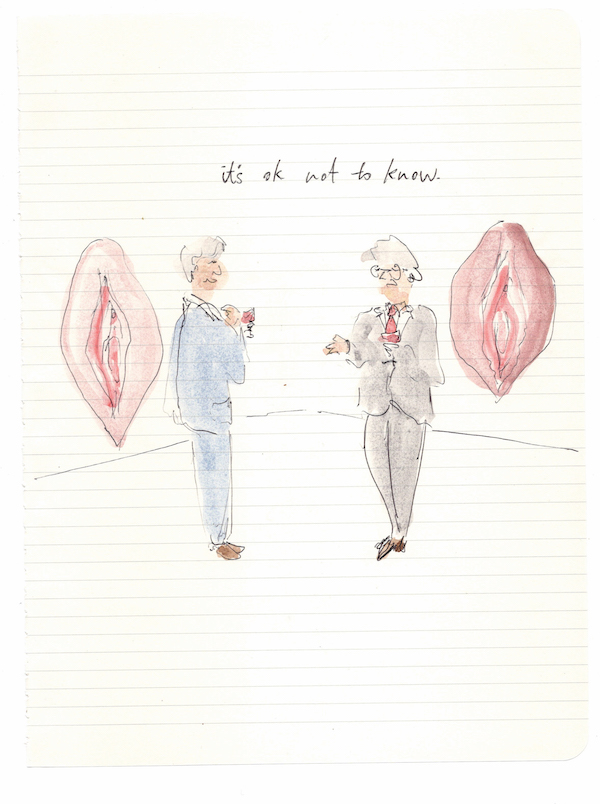

REALISATION EIGHT: Contemporary art is impossible to define.

What many people understand as Modern Art is mostly the narrow chronicle of orderly begats – great (white) men, who influenced other great (white) men, often in Europe and America. This understanding dramatically shifted in the period of contemporary art – emerging around 1989. Contemporary art is open-ended endeavour that addresses the political, economic and social issues priorities of now, and this now-ness has expanded the field of contributors, ideas and practices far beyond the traditional privileged minority who have historically shaped culture. Contemporary art making is a result of an endlessly shapeshifting idea that can include anything from a grand sculpture to a pile of dirt. By its very nature, contemporary art eludes any definition, and collectors who come to terms with this no longer get hung up on whether that fire hydrant is part of the show or not. They think of it not as a full stop, but a hyphen – or perhaps series of hyphens that either continue and disrupt ideas, practices and materials. After all, things have to change, even to stay the same.

Micheal Do