Cultural Capital: Talking about your collection

How to not sound like a pompous p**** when talking about the artists in your collection.

Words: Andrew Frost, Carrie Miller, Tai Mitsuji

Illustrations: Coen Young

STARING AT MY FEET, a friend recently observed: “fun socks aren’t a substitute for a personality.” Good to know. I’ve long suspected, however, that art might be able to fill this very gap. I’m almost certain that there are some people out there operating under the assumption that if you stand next to an interesting painting for long enough, others might begin to call you interesting as well. Indeed, a subset of the population seem to be so taken with the idea that they bring the artwork home and stand next to it when- ever they have company. Yet this new found depth of character and permanent proximity to the work comes with its own set of perils: what do you do when someone actually asks you about the artwork, or worse, the artist who made it? And, more importantly, how can you avoid sounding like a pompous prick? There are no right answers, so let’s talk about the wrong ones.

Tai Mitsuji

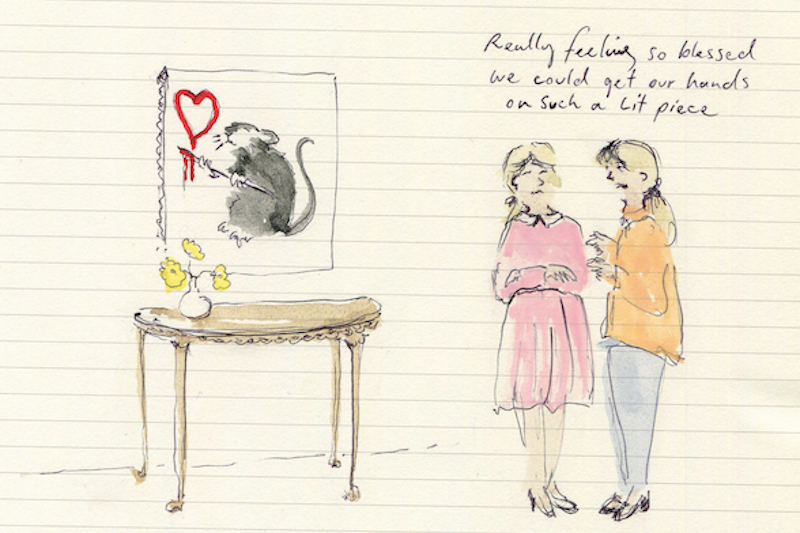

THE SELL OUTS

The good thing about being smarter than the average art collector is that you are an early adopter of artists who will go on to have commercial success. The bad thing is that you will be an early adopter of artists who will go on to have commercial success. It can be super awkward when an artist whose work you’ve been collecting hits the big time and starts pumping out the same series of banal paintings like stale cheese- burgers at a family restaurant. Obviously, you’ll want to cash-in on these sell-outs, just make sure you get the word out that you “discovered” this artist when they were a nobody with credibility. Casually drop into polite conversation with critics and curators that you collected said sell- out’s work when they were still showing at artist-run spaces and lament the fact that commercial success has turned his practice into a caricature of itself. At the same time, make sure you keep talking the artist up to your rich mates.

Carrie Miller

ARTISTS YOU KNOW PERSONALLY

“So this piece is by Jason, that print is classic Jim, and those sculptures – yes, the ones just to the left – are Jerry’s”. If you have uttered this sentence, or anything like it, know this: everyone in the room hates you. There is perhaps no bigger flex in the art world than casually dropping a first name into conversation. It’s familiar, it’s intimate, and it leaves your listener playing catch up. The first name suggests that you and [famous Australian artist] have a history that predates any critical attention that accompanied their latest exhibition. The two of you have gotten drunk together at the studio, letting the fog of turps wash over you until the early hours of the morning (and the world needs to know!). You not only own one of their art school pieces, you own a part of them. Why? Because, when it comes to [famous Australian artist], it’s personal.

Tai Mitsuji

CONTROVERSIAL ARTISTS

We once lived in a simpler time, when mediocre European film directors could get away with drugging and assaulting 13-year-old girls in the safety of their celebrity friend’s hot tubs. Now that the #Metoo movement has poured some feminist acid rain on this misogynist parade, are you going to have to distance yourself from the artists whose work you collected before the world found out they were a wife beater, sexual predator and/or violent drunk? Perhaps. Or you could learn to justify these degenerates with some fancy linguistic footwork. When someone at an opening says: “How could you support that misogynist?”, try saying: “His work has a subtle criticality that’s lost through literal-minded interpretations of it. From a poststructuralist perspective, I think we can understand it as problematising dominant notions of masculinity through parodic gesture.” Or you could just keep your collection on the downlow until feminism falls out of fashion again.

Carrie Miller

INDIGENOUS ARTISTS

Of course, as a prominent contemporary art collector, you have a keen sense of social justice. You supported the Rijksmuseum’s decision to rename hundreds of thousands of works in order to remove racially offensive language. You would never buy Colonial paintings and you definitely have some guilt that you don’t own any Indigenous art. Not being able to justify this fact to yourself is one thing, not being able to justify it to others is social suicide. That’s why you need a humble-brag ready to go when the topic of Aboriginal art comes up at the next benefactor’s dinner. Have a go at this: “I am so deeply committed to ethical collecting practices that I made the conscious decision a long time ago to wait until I was better informed before acquiring Indigenous work. I certainly don’t want to further compound the oppressive colonising practices of the past through my own Western ignorance.”

Carrie Miller

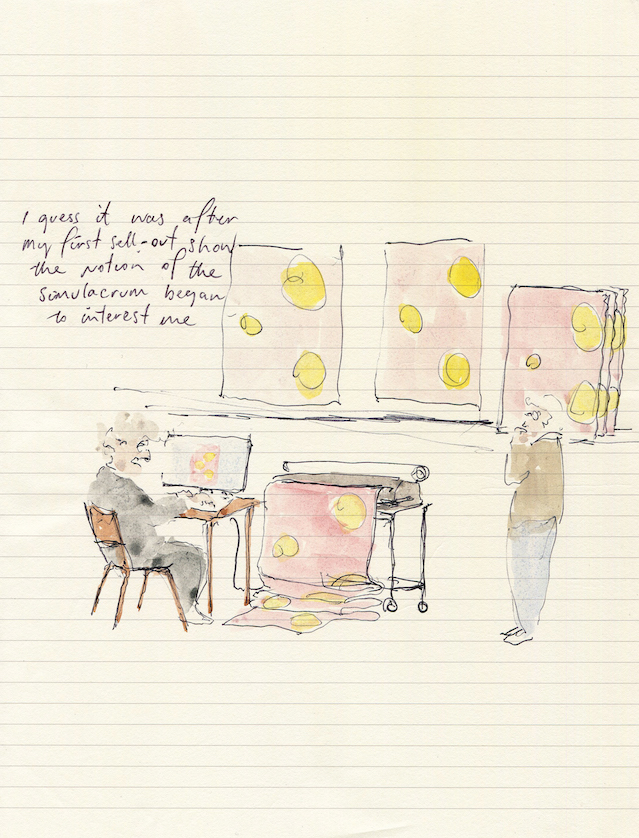

LATE-CAREER ARTISTS

Some artists who have achieved the exalted heights of “senior” status, really have no fucks left to give. They may have suddenly started reinterpreting their early works in a new medium, or maybe their late work is just a tired pastiche of their signature style. Buying in late on a senior artist’s work is like buying blue ribbon stock at the top of the market. Sure, it’s not sexy or exciting, but the ROI is assured (at least as long as the market is strong when you sell). Also these late pieces tend to be very big, taking up whole walls, or giant plinths in the garden, or whatever, they’re just huge! Why did you buy it? Because you can. But don’t say that. Your stated rationale here is that it’s a good idea to have an example or two of the late work, for completeness’ sake.

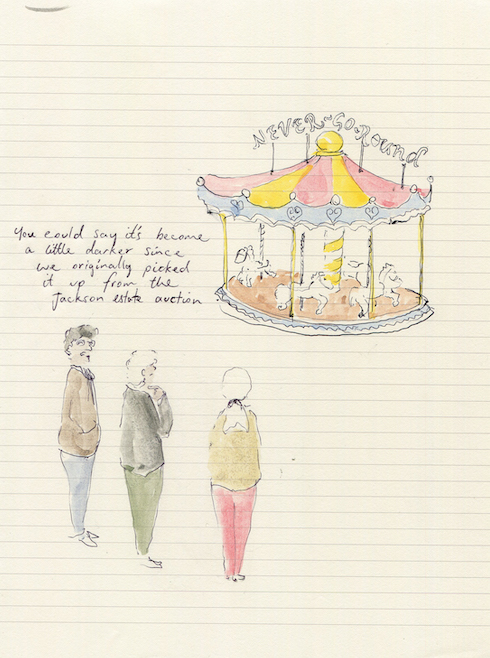

ARTISTS YOU STARTED COLLECTING BEFORE EVERYONE ELSE

Many artists – at least the collectable ones – go through an early burst of energetic enthusiasm, followed by the heady rush of critical and commercial success, before tailing out into the awkwardness of mid-career. In that first stage they’re showing in ARIs, perhaps they’ve got something interesting in an art school grad show, or maybe they’ve got a kickass Instagram account. Whatever it is, if it’s cheap and available, your time as a collector is now! When people realise you have early work in your collection, proudly displayed next to the later key pieces that were featured in a magazine spread or a museum survey show, the only alibi you’ll ever need is that you had an eye for the work before all the latecomers. So what if it’s atypical, in a different medium, or on a totally differ- ent theme? The key here is completeness: it’s not a real collection until you have everything.

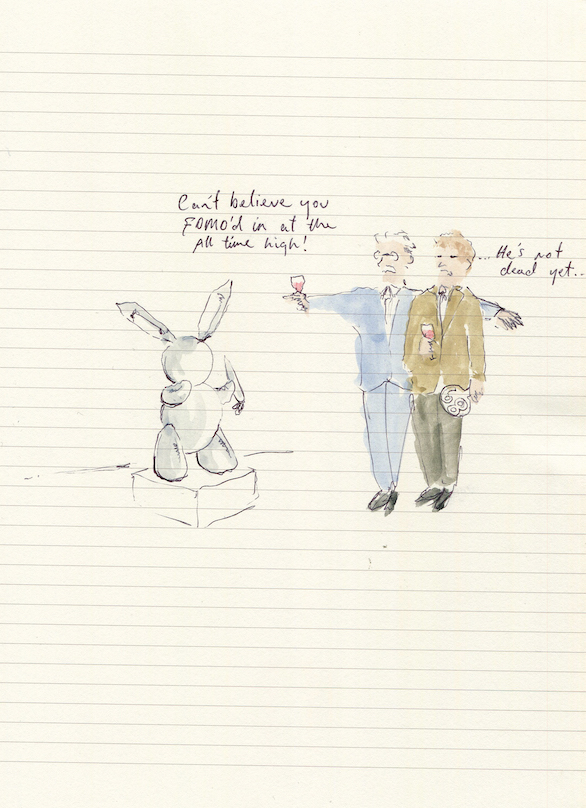

ARTISTS EVERYONE ELSE IS COLLECTING

Imagine for a moment that you are a gazelle. You are beautiful and swift and move across the African grass- lands in a vast heard. When it comes time for a drink at a river bend, you know enough not to go wandering away on your own. Why? Because if you go alone, a lion will almost certainly take you down, and chew on your neck until you are dead. But in a crowd, you’re relatively safe. This rule also applies to art collecting. Being a collector who collects the same stuff that everyone else has isn’t going to make you a brave and independent gazelle with a unique and interesting collection, but rather a confident creature with an almost guaranteed ROI 15 to 20 years down the track. What you need to tell people is that they should avoid possible lion attacks by continually leaping and darting between openings and trays of canapés, while buying up any available [collectable Australian artist]’s. Hey art world predators, you’ll never catch me!

Andrew Frost

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 89, JUL – SEP 2019.