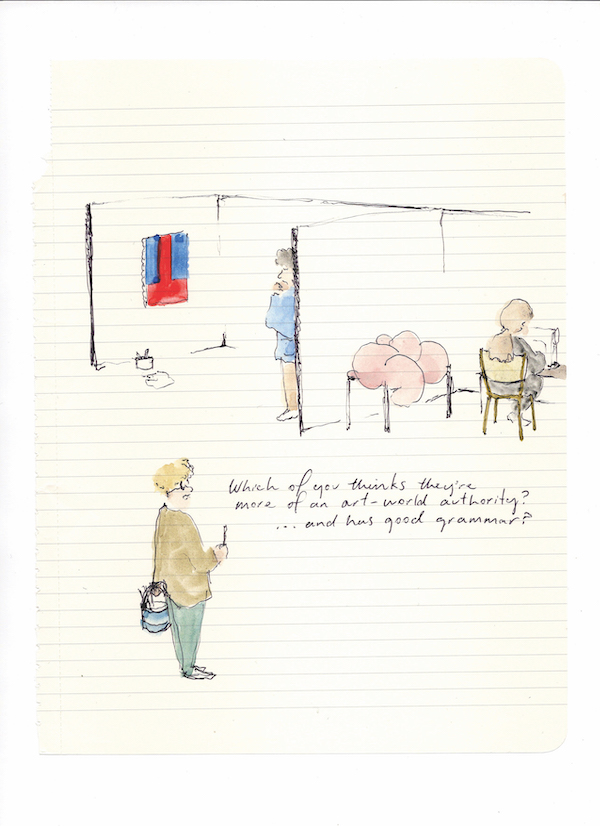

Cultural Capital: Smoke and mirrors

Our writers reveal the smoke and mirrors of the art world.

Words: Andrew Frost, Carrie Miller and Tai Mitsuji

Illustrations: Coen Young

IT’S SAID THAT a good magician never reveals their secrets. It’s the unspoken covenant that binds the five-year-old in the top hat with Harry Houdini: the smoke and mirrors. The art world turns on a similar agreement. From the canonising of the artist to the consecrating of the gallery to the ordaining of curators, the art world keeps a tight grip on the chalice of cultural capital.

Yet despite all of these elaborate ceremonies, the whole enterprise is under- pinned by a few simple tricks. From the outside these illusions dazzle, but as soon as an insider tells you about the card up the sleeve, the whole thing begins to fall apart. The real question is do you actually want to know? Do you really want to be disappointed? If so keep reading, because we always disappoint.

Tai Mitsuji

THE MOMENTARILY HOT ART PRIZE-WINNER

It’s fairly obvious why the mainstream media gets over excited when someone wins a big art prize. There’s an undeniable newsworthiness to the event that guarantees coverage, and if the winner has a heartbreaking or worthy backstory, there’s a human connection as well.

This tends to distract us from the nature of prizes. Art prizes can do many things: reward talent, highlight underappreciated media, support social justice, and develop and expand collections. But they are also hype machines. Pretty much everyone knows that art competitions are largely random in selection and mostly subjective in their decisions, so who wins and why isn’t on the basis of fairness but for many other reasons.

So, we can feel genuine pity for the (momentarily) hot art prize-winner who thinks they’re on the red carpet because it’s all so fleeting and will soon fade away. Unless of course they win more prizes and we all realise that this isn’t hype, this is the real thing. Outta my way!

Andrew Frost

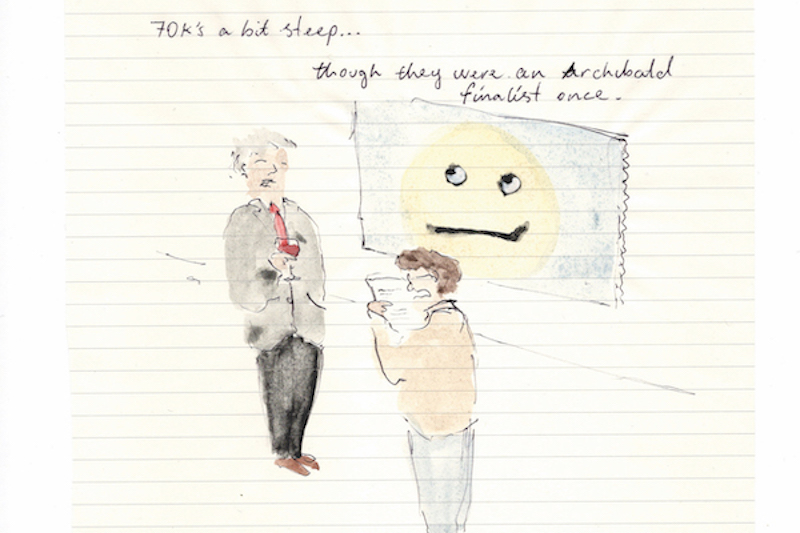

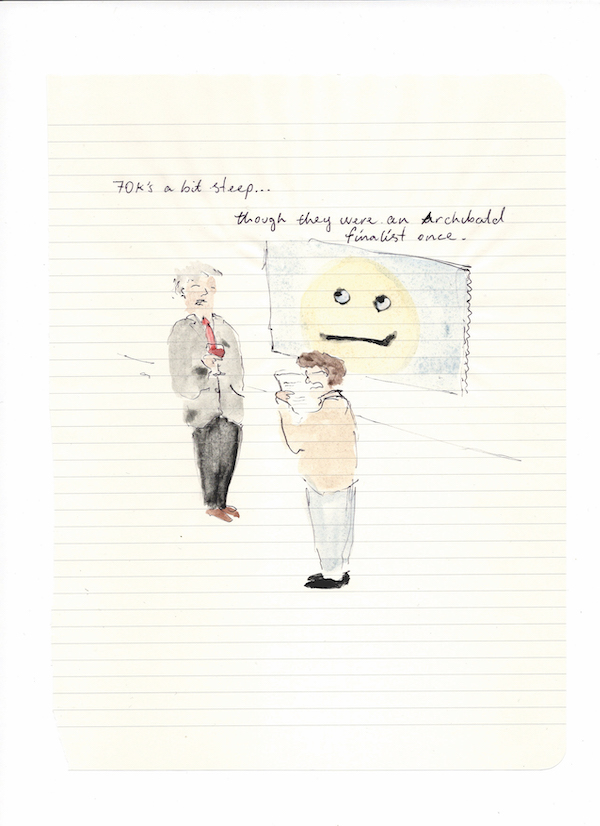

THE UTTERLY UNINTERESTED GALLERIST

An uninterested gallerist is a lot like an absentee father. They never get up from their desk, they never greet you at the door, and they aren’t going to call at Christmas. Yet their apathy, fleeting interest, and inability to recall your name only drives you to strive for their approval more.

Suddenly, you find yourself talking about that art fair that you didn’t attend in Hong Kong (“Basel was amazing this year”), and that artist that you don’t know (“Keith is an old school friend”). This is all in the hopes that they will eventually deem you worthy to give them some cash… a lot of cash, actually. In fact, now that you’re sitting at home staring at the piece on your wall, it’s far too much cash. Is that a zebra? Why did you buy a zebra? Oh well, it’s all worth it for a conversation with dad.

Tai Mitsuji

THE HALLOWED GALLERY SPACE

When cashed-up bogans want to signal their upwardly mobile social status on Facebook to those school friends who judged them for getting knocked up as a teenager, they do it with stuff. Stuff that they often put in their driveways.

Multiple cars, jet skis, at least one boat, and a pimped-out caravan that could be the trailer for a gangsta rapper on the set of a music video. Inside their McMansions’ media rooms, you’ll find oversized entertainment centres with surround sound, alongside the classy photographic portraits they commissioned to make their family look just like the Kardashians.

Weirdly, posh people do the exact opposite. They get rid of everything in order to signal status. There’s usually nowhere to sit in the spaces occupied by the cultural elite. Or if there is, it’s hard to tell if you’ve taken a load off on a lounge or a priceless sculpture.

The ultimate expression of this is the white cube of the high-end art gallery. These spaces invoke a sense of awe in those who visit; a stillness that inspires quiet contemplation. That’s until the rude assistant reminds you that the gallery doesn’t allow food and drink to be consumed on the premises, and you storm out with your half-eaten pie, cursing the pretentious wankers who sucked you in to thinking there was something special about art in the first place.

Carrie Miller

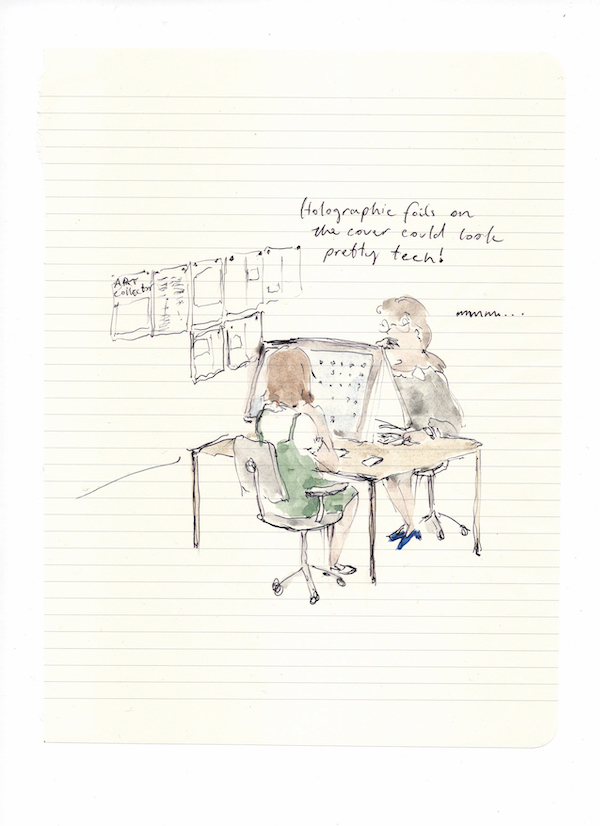

THE COOLER THAN THOU ART MAGAZINE

Most cool art magazines look, well, cool. The design is bracing, and they look great on a coffee table. But what’s going on inside? Is it credible? Most cool art magazines try to convince you they are cool because of their layout, and their content. Canny magazine art directors will slowly adjust the look and feel of a printed art magazine to keep things fresh and even change format for a complete reset. For their content, most art magazines trumpet the artists, galleries and other art world identities found inside their covers to make it all feel exciting and zeitgeisty. In the heat of the cultural moment it’s usually often hard to measure whether it’s just pure PR smokescreen or if it’s actually credible – but one way to measure the quality of a magazine’s content is to look at its back issues. If an artist covered 10 years ago, or even just five or even two years ago still has credibility, chances are the art magazine has credibility, too.

Andrew Frost

THE ROMANTIC SUFFERING ARTIST

“Death. Life. Abstraction.” A piece of advice: never ask the artist slumped in the corner about their work. You know the guy – and, yes, it’s always a guy – dressed in black, garbed in smugness, desperate to tell you how little they care. “Death. Life. Abstraction.”

This mantra and a dark scowl will sustain him throughout most conversations, as he manages to pass off vacuity as mystery. The artist is aberrant, lost, prodigious, oppressed, underappreciated, lonely, existential, tortured. He’s a few bottles of whiskey away from going full Dutchman and mailing you his ear… or so his dealer would have you believe.

If he were born in another time or place, he might have been a preacher or a prophet, but he wasn’t. So instead of genuflecting before his effigy, we’ll just have to content ourselves with kneeling before his paintings. Either way, he must be worshipped.

Tai Mitsuji

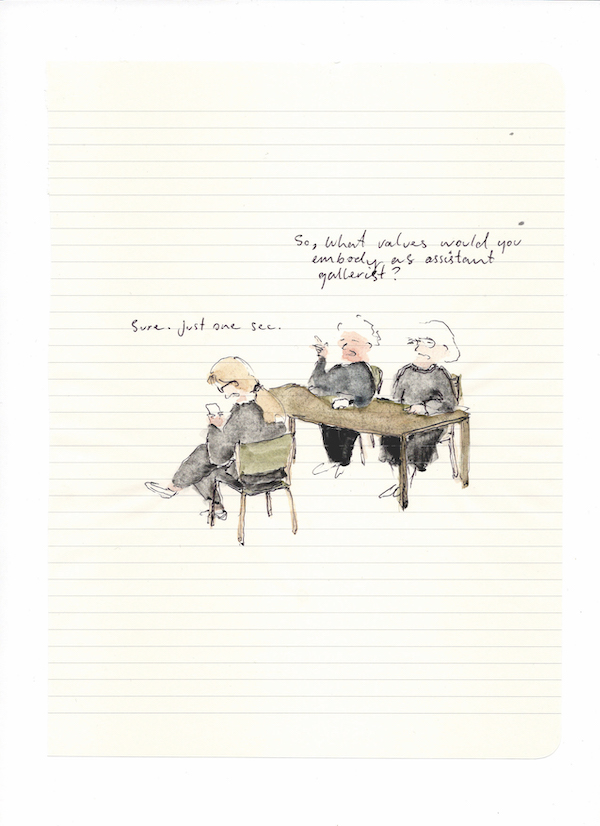

THE SUPER INTELLECTUAL CURATOR

The cliché of the art curator is of an impeccably dressed purveyor of high-end contemporary art. With architectural hair and glasses, and a European accent of uncertain origin [Finnish? Flemish?], the black-clad curator is always impressive to Australians and suggests a level of authority mere locals can only aspire to. Like most professions, art curators have to fake it ‘til they make it – and so the standard wardrobe is usually accompanied by a good dose of up-to-date artspeak, perhaps dropping terms and phrases hot from American art journals, and some street talk to indicate hip #wokeness.

Is it all smoke and mirrors? Well, you have to work extra hard to find out if they really do have the knowledge to go with the look – is their exhibition credible? Has it got an understand- able idea? Who are the artists in the show? It’s worth noting the counter trend, which is the curator with an extra-broad accent, daggy clothes and suburban lifestyle. These curators are offer- ing a different kind of authenticity, but is it any more real than the standard Eurowanker? The same measure applies.

Andrew Frost

THE FANCY ART SCHOOL EDUCATION

Well before you heard of that artist everyone is raving about it, there’s a good chance they laboured through a degree at one of the major urban art schools. There’s also a chance they were taught by a much older artist whose name you only vaguely recognise. And herein lies the problem.

Art school lecturers are constantly surrounded by bright young things whose practices are full of the promise that has leaked out of their own like air out of worn-out old tyres. This means they have to find a way to assert their authority over these little know-it-alls in other ways. And because they can’t always rely on their Pygmalion charms to seduce their proteges after too much warm wine at a gallery opening, art lecturers assert themselves through their wizardry with half-baked ideas.

Undergraduate students are susceptible to this power play – they are still walking around campus with a copy of William Burrough’s Junky sticking out of the vintage smoking jacket, even though the strongest drug they’ve ever taken is one too many highly caffeinated beverages at an outdoor music festival. And they are still pronouncing Nietzsche ‘Nitchkee’.

Academics who weren’t classically trained in philosophy teach students about great German thinkers with the type of confidence that can only come from intellectual mediocrity. The result is a kind of conceptual Chinese whispers that leads to the incoherent mumbo jumbo you find in an exhibition catalogue.

Carrie Miller

THE EXHIBITION CATALOGUE

Now that you know where the conceptually opaque bullshit that pollutes the atmosphere of the contemporary art world and threatens to choke the intellectual life out of you emanates from, we can address the elephant in the room. No, not that sculptural installation that ironically critiques colonial practices in India; it’s the exhibition catalogue that accompanies fancy exhibitions.

It’s true that catalogue essays have become more readable than their high (low?) point in the 1980s, when applying feminist critiques of Derrida to British sitcoms was all the rage. But it’s still easy to thumb through a catalogue and see the words “abjection” and “liminality” being thrown about like a midget in a Queensland pub. The main offenders are artists themselves. When they can’t get a real writer to say some- thing about their work, they do it themselves or, God forbid, they get their artist mates to do it for them. These “mates” have a vested interest in making the work sound important, because they started an artist-run space together and so it will reflect badly on them if their “mate” is a light- weight. Once they become successful and no longer need mates, they will tell anyone who’ll listen about how banal their ex-friend’s work is.

Carrie Miller

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 90, OCT – DEC 2019.