Cultural Capital: Why do people collect?

To contribute to general knowledge? Or your own general ego?

In the second of this three-part series, Carrie Miller and Andrew Frost explore some more of the reasons people collect art.

Words: Carrie Miller and Andrew Frost

Illustrations: Coen Young

SOCIAL STATUS

THERE COMES A time when every collector must decide whether it’s a good idea to own a work by a [well-known photographer]. Everyone else seems to have at least one, sometimes more than a few, so it seems like a good time to get in on the market. The photographs of this particular artist have proven resilient at auction, with no appreciable drop in price in close to 20 years, and a few of the artist’s most famous images are setting record prices. And then there’s the added bonus of enhanced social status… want to take look at my latest acquisitions?

Like most investments, owning art by well- known artists is a sure way to climb the social ladder. A nicely rounded collection will impress other collectors you might happen to invite to your home for an elegant dinner. It’d be even sweeter if the works you have on your walls are highly desirable. The simple economics of desire dictate that those who own the most desirable objects are the winners, but the balance between simple satisfaction in your acquisitions, and an immodest pride, can be tricky.

Faking indifference to what you own is a quick and easy route to losing social status. Fellow col- lectors – and even curious onlookers like the guy who has come around to fix the pool filter – can spot a phoney baloney fake modesty almost immediately. If you’re so indifferent to your collection, why do you even bother to hang it in your home when it’s a more advantageous tax arrangement to keep it all safely secured offsite? On the other hand, an actual modesty and privacy about your collection prompts the question – what’s the point? Imagine you invested all your spare cash buying art – and supporting artists – but never telling anyone about that until you’re in your 80s, and then the only time you tell anyone about it is for a documentary about you and your husband’s collection of conceptual art? It beggar’s belief.

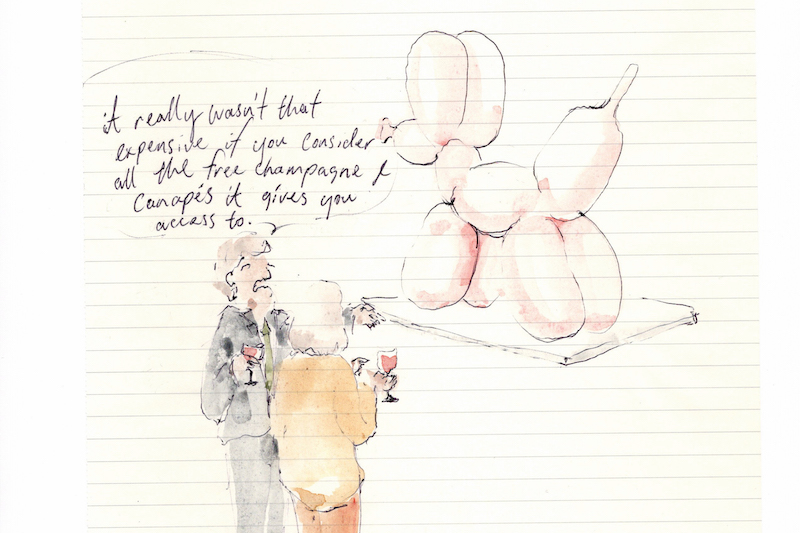

As we’ve noted before [see Quest for Immortality] donating your collection to a public gallery or museum is a sure-fire way to get your name added to the inscriptions chiselled into the architrave. Those are the special donors who thought so little about the wellbeing of their shareholders, employees, family and descendants [in that order] that they decided to give away millions of dollars of art for little more than their name on the museum wing and entry to every black tie event that will ever be held in it. While this pinnacle of social status in the art world belongs to a select few, there’s no reason you shouldn’t start planning early.

Imagine you’re one of those fabled internet millionaires from the late 1990s who came into the market loaded with cash and ready to buy. Now remember that time you went to that art- ist-run space in Chinatown and you saw early works by [well known Australian painter] and you bought the lot instead of humming and haw- ing about the fact they were $200 each. Now fast-forward 25 years and imagine you’re stand- ing in your own private collection of [well known Australian painter]’s work. HOW YOU LIKE ME NOW WORLD?!!!

Andrew Frost

THE URGE TO GAIN AND DISSEMINATE KNOWLEDGE

Not everyone appreciates art’s pedagogical value. As one person put it on an online discussion board: “Whenever I look at a piece of art… I just think it’s ugly and it shows that the artist is lazy. Stuff like that makes me think an artist is just bullshitting about their art having a special meaning.”

These days, the belief that art is a unique repository for cultural knowledge seems as archaic as having a domestic library stocked with leather-bound books. This wasn’t always the case. An appreciation of art was once considered integral to the type of cultivation of the mind nobly pursued by the intelligentsia.

There is a rare breed of contemporary art col- lectors who remain faithful to this higher pursuit, both as an individual desire for intellectual refinement as well as for the social good. Not only are they committed to the development of a personal collection of critically significant work, they understand themselves as custodians of the knowledge these cultural products hold. They feel an almost moral obligation to disseminate this knowledge through various philanthropic endeavours, as if the future of human civilization depends on it.

Such collectors realise these lofty goals by div- ing into the deep end of the contemporary art world. Most people who acquire art for investment purposes will enjoy procuring the glossy monographs that accompany the exhibitions of leading artists. But they will remain unread on the coffee tables of their beach houses. Collectors concerned with the value of art as a special form of knowledge will absorb as much information as they can get their hands on about the artists they collect, educating themselves about the conceptual motivations of the work and its relationship to the broader socio-political concerns of contemporary culture.

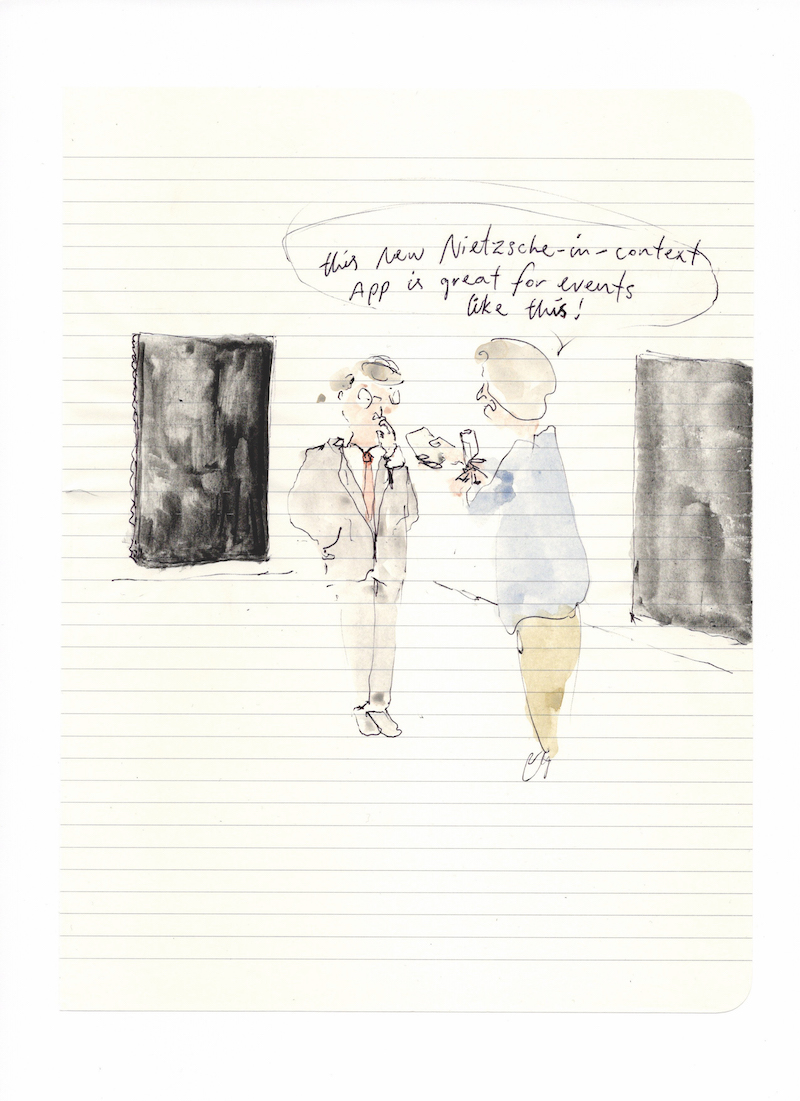

This takes a lot of psychological stamina. At the beginning of this pursuit, it involves bearing passive witness to long and excruciatingly pretentious conversations about the philosophical possibilities and limitations of post-colonial identities. Only the most committed collectors survive these intellectual posturings. Over time, they will get a gist of the insiders’ lexicon and become confident enough to throw around terms like “Husserlian intentionality” as casually as “send the bill to my office”.

It also involves a lot more than tolerating tepid wine at a relentless schedule of exhibition openings. It requires the cultivation of relationships not only with artists, gallerists and museum directors, but art critics and scholars. And it requires a strong constitution for the antagonism of others who now see you as a pretentious wanker. Of course, as a result of reading The Cambridge Companion to Nietzsche, you have come to identify this antipathy as a form of ressentiment – a hostile projection of another’s own inferiority. This will provide you with the necessary comfort to continue on your noble path.

Carrie Miller

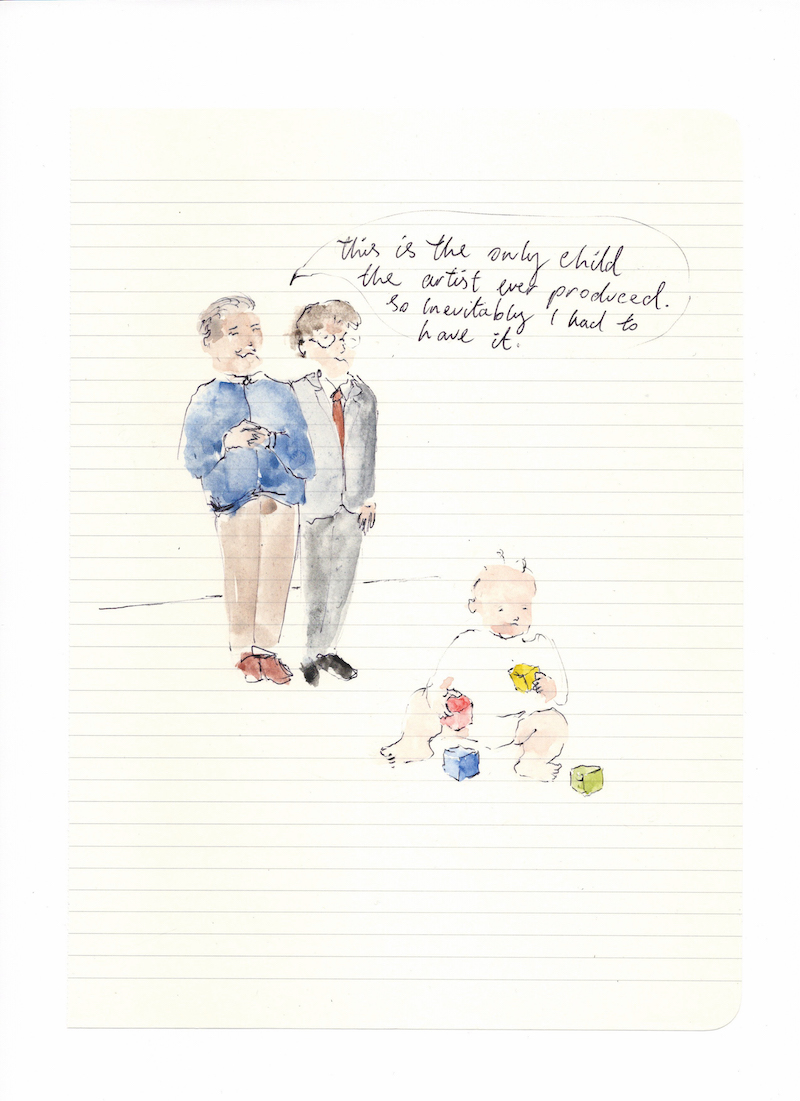

EGO ENLARGEMENT

It has always been a part of art collecting that the collector who wants to enlarge their ego will always purchase the most expensive art, or the most obscure, or the largest, or the oldest, or the rarest, or the best examples by artists that everyone else wants to collect. But with the top 10 most expensive paintings at auction currently starting at $172.5 million USD and going all the way up to $450 million USD, getting in at the true top end of the market is now the sole preserve of Russian oligarchs, Gulf state princes or faceless corporations. So, what’s left for the run-of-the-mill everyday collector with a few lazy million to invest in art?

There are some options to gratify the ego. One could collect in depth, buying all the best work of a single artist, until you are the collector known for having the work of that certain artist. You can go so far as to rearrange the house so to feature all the artist’s signature works where hapless visitors to the foyer of your suburban ranch will literally run into your taste. Imagine – early examples of the adolescent style, those one or two works that won big prizes, half of the last exhibition and the entirety of the one be- fore. Your name will become synonymous with that artist, and for good or ill, like they say in Texas hold ‘em, you’re ALL IN.

Another way to build your art ego is have all the work on a particular subject, theme or movement. No one ever dreamed that Australian art would have its own notable examples of Un-exceptionalism, yet you’re the collector who has them all, from the lesser known fringe artists to prime examples of the three or four best known artists who dabbled in the style before moving on to their mature work. Your name will be synonymous with the unexceptional.

The key to true collector ego boosting is to be recognised for whatever it is you collect. You could pay for the publication of a fine book on your collection, or you could arrange an exhibition of your collection in an obliging regional gallery, art school or lesser museum, or even better, if you’re on the board of a major museum, you could get your collection shown there, boost its potential resale value and then have a sweet tax write off when you donate the whole thing [see The Quest for Immortality].

Or you could collect art in a way that has not be done before, such as becoming a pioneer of collecting the new art of Internalism, where the art that you commission from leading Internalist artists is literally installed inside your chest cavity. You’d carry it around inside you, and although no one would really know it’s there, the door in your chest could swing open so passers-by could look inside at your beating innards and the decorative baubles that hang there like a mad woman’s Xmas tree. No such thing actually exists, obviously. Well, not yet anyway, but imagine being the first!

Andrew Frost