Lifecycle of a collector: Publish and be damned

There comes a time when a collector begins to toy with the idea of a book on their collection. Let’s examine the arguments.

Words: Louise Martin-Chew

The economics of publishing books on an art collection became obvious to me when, after the opening of Hobart’s MONA, I bought a copy of Monanisms (2010). When it arrived in the mail, it had been hand-signed and annotated on the title page by MONA director David Walsh (and curator Elizabeth Mead). His note begins, “I looked you up…” and ends with, “Thanks for believing in the book.” This charming personal touch may speak to the less than dynamic economies of art book publishing in Australia (when each sale is notable).

Art book sales statistics are difficult to access. Specific titles may be searched from the Bookscan database (by those with licensed access), but art book types – monographs, biographies, catalogues and collection books – are not differentiated. My research suggests that personal narrative (artist biography) outsells monographs, and that notoriety drives sales.

So, where does that leave books about art collections? Many become a biography of the collection (and sometimes the collector, depending on how closely the collection is tied to a person). In the case of Monanisms, an incredible production with a hand-stitched cover, slipcase and literal moving parts delivers a partial biography of Walsh. In his inimical way, he talks around the reasons for his museum and refers to the book as “distilled MONA”. It remains (some 10 years later) one of the most charismatic books on my shelves. Given its status as a collection book for a museum (with visitation aiding sales), it is likely to have sold more copies than a private collection might have. (MONA could not supply sales figures for this book.) Yet perhaps the reasons for a book, where an art collection is concerned, is for purposes quite distinct from sales.

Patrick Corrigan AM is a notable Australian benefactor. He has published not one but four collection books to date – a record that is clearly testimony to his love of books as well as his love of art. The books trace the development of his significant interest in Aboriginal art. His first book, New Beginnings: Classic Paintings from the Corrigan Collection of 21st Century Aboriginal Art (2008) followed the sale of his earlier collection of Aboriginal art and new beginnings in this area post-2000. A few years later, after seeing Judith Ryan’s Colour Power at the National Gallery of Victoria, he was inspired to publish a more extensive book titled, in tribute, Power + Colour (2012). This was followed in 2015 by Gabori: the Corrigan Collection of paintings by Sally Gabori. This instinct to share his enthusiasm for Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori paintings is integral to what Candida Baker describes in the book as Corrigan’s educative ethos as a collector. Each of these books has been published “as a way to share with the public his knowledge of and love for Indigenous art”. The most recent (limited edition) book is on his collection of bookplates.

Corrigan tells me that the books were “spur of the moment. I got such a kick out of New Beginnings that I did Power + Colour and then Gabori as well. Satisfaction is the reason you do these things.” Corrigan’s advice to other collectors who plan to produce books is to “buy good help”. Credible writers, high production values, and commercial distribution contribute greatly to the shelf life of a collection book.

Curator Lee Kinsella, who co-edited Into the Light: The Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art for UWAP (2012) with John Cruthers, suggests that, “A collection publication is a time capsule, reflecting aspects of the collection and the ways in which it is contextualised at a given moment and in a particular place. A collection book offers a way of accessing images and information about a collection. By necessity, it’s a selective process and part of an ongoing reflection on narratives that relate to works of art in a collection.”

Whether or not a book impacts on works in the collection also depends on circumstances. Inclusion in a book adds to the provenance of a particular work and the selection process may assist the collection itself. Some have been significant sales successes, notably the Laverty Collection of Aboriginal art which was the subject of Beyond Sacred (first edition 2008) which sold out and was among the Australian Art Market Report’s list of top 10 books that year.

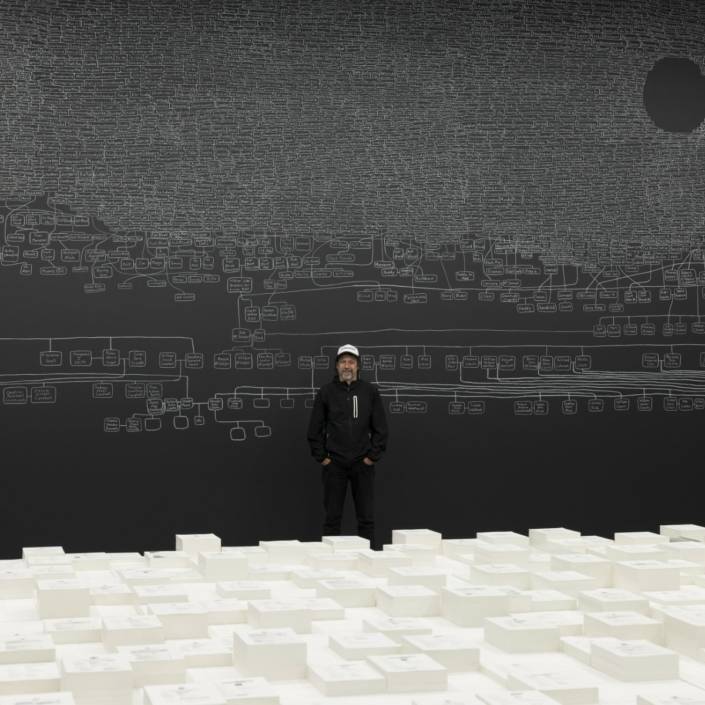

New collection books in recent years include White Rabbit Gallery’s two collection books, the first Big Bang (2010) and 99 Artists (2019). Melbourne’s Lyon Housemuseum produced a visitor guide to the collection in 2016, and Muse by Terri-Ann White and Janet Holmes à Court selected 150 of 5,000 works in an effort to create an intimate understanding of the collection (UWA Press, 2017).

“For me, much of the value of art books lie in quality colour reproductions,” says Kinsella. “I am the type of researcher who has piles of books open to various images as I write. Providing accurate reproductions of many works of art is important. And as useful as online content about works of art can be, there remains something particularly valuable about a well-produced and researched collection book – the arrangement of word and image in the run of pages and the tactility of the book itself.”

As a book buyer, I often buy collection books as reminders of an experience had with works of art in particular places. What draws me back to their pages over many years is the time capsule they comprise, writing with images, locating an object in a time and place with context. Like Corrigan, I’m a believer.

To find out more about publishing a professionally produced collection book contact Art Collector’s Editor-In-Chief Susan Borham.