Nola Campbell: Mapping a different time

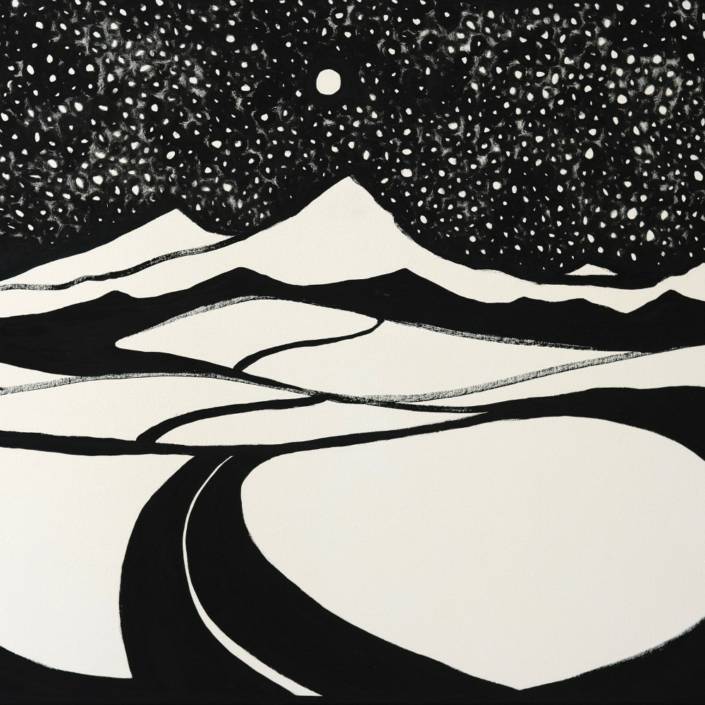

Nola Campbell’s energetic paintings preserve memories and travel routes from a different time.

Words: Timothy Morrell

The gradual passing of the senior desert men who introduced the rest of Australia to their stories via portable paintings has been a sad loss to Australian art. Now the wives and daughters who survived them are chiefly responsible for leaving permanent records of traditional visual culture. Initially reluctant to paint because it seemed like men’s business, the senior women have become the driving force behind art in the desert.

The loose, energetic brushstrokes that recall the look of body-painting often distinguishes the work of the senior women painters. They have played a leading role in the transition from strictly formal images in natural ochre colours to the brighter, freer paintings that are now preferred by the market.

Nola Campbell’s Country is about half way between Alice Springs and the coast of Western Australia, in the Gibson Desert. Born in 1948, she lived the traditional peripatetic life until first contact with white people the 1960s, after which her family was relocated to the settlement of Warburton, among the last to be forced into large permanent communities by the government policy of intervention. She is one of the very few remaining artists who can remember a time when traditional life was completely intact. She now lives at Patjarr a tiny remote settlement in the Gibson Desert where making paintings on canvas did not begin until this century.

Her first solo exhibition, Rockhole to Rock-hole, was at the Suzanne O’Connell Gallery in Brisbane in 2005. The exhibition’s title neatly conveys the character of the paintings she was making at this time. They were grids of travel routes between rockholes, which were indicated by the familiar concentric roundels of desert iconography. The roughly square spaces defined by the grid lines were filled with blocks of various solid colours. There has been significant development of her style since then, but Suzanne O’Connell observes that “her paintings are all maps”.

Nola Campbell was one of the artists in the Yiwarra Kuju: The Canning Stock Route exhibition which was presented at the National Museum of Australia, Canberra in 2010 and toured until 2013. The exhibition, like her work, was very largely about travel. It was a history, from an Aboriginal perspective, of the chain of wells that made it possible for drovers to take cattle long distances through Western Australia. Campbell remembers and embodies that history. The impact on Indigenous peoples was destructive, but today it facilitates easier travel through the country for the traditional custodians.

Another Indigenous Australian art project for which Campbell’s work was particularly appropriate was the group of painted car bonnets, an initiative of Michael Stitfold who was then the art advisor at Patjarr. Travel between important sites is now done in cars rather than on foot. The metal panels were reclaimed from the places in the desert where the cars had died and been abandoned. The full set of five was acquired by the Queensland Art Gallery, where curator Diane Moon points out the ironical cycle of artists painting to get money to buy cars, which are then recycled to become paintings, which are sold to buy more cars.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 78, OCT-DEC 2016

Image: Nola Yurnangurnu Campbell, Tika Tika, 2016. Acrylic on canvas, 50.8 x 76.2cm. COURTESY: THE ARTIST AND WARAKURNA ARTISTS, ALICE SPRINGS