The Olsen Obsession

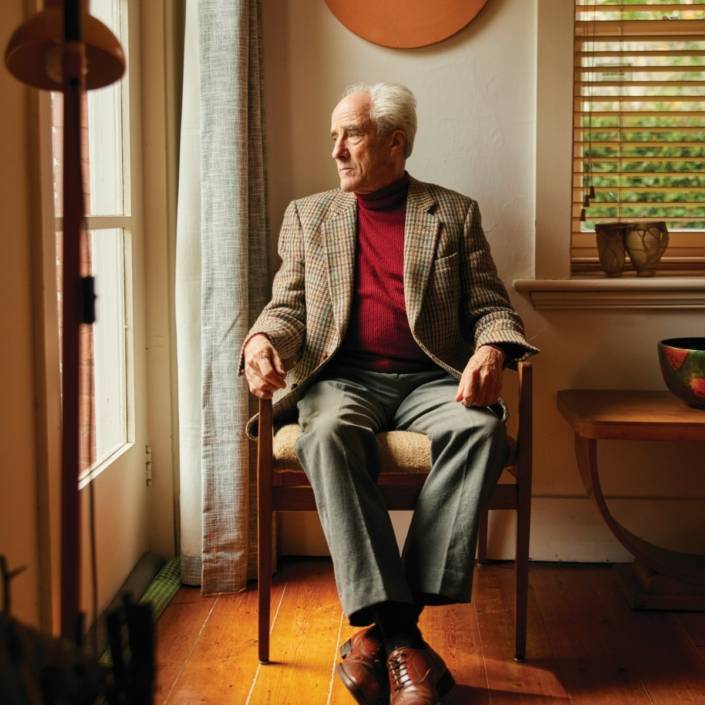

Turning his back on artworld tall poppy antics, Tim Olsen credits his staff and artists with his gallery’s thirty years of success.

Words: Courtney Kidd

Photography: Anna Kučera

Obsession, the action of beguiling, and its healthy neighbour… persistence, the characteristics that have made Tim Olsen and Olsen Gallery so successful. During its 30 years, Tim has presided over more than 900 exhibitions, connected with a flotilla of artists and made many deep friendships. But 2023 may be his toughest year yet. On 11th April this year his father, renowned Australian artist, John Olsen, died. Further, the year is bracing to be financially hard, one where art as a luxury item, may not be priority spending.

On 20th June, 1993 the Sun Herald’s social pages recalled the opening of Olsen Carr Gallery in Paddington, the svelte young Tim photographed with artist William Rose. The article noted that the city’s newest art gallery was “flying in the face of all who say art galleries cannot flourish in the financially spare 90s.” Cut to 2023 and Olsen Gallery, nurturing a host of Australia’s leading artists, is thriving.

“Sanity for me today is knowing that the gallery is 30 years old and that I’ve never veered from my direction,” says Tim. “I’m happy where I’ve ended up though feel I’ve only just begun. But losing my father and also my friend, artist Nicholas Harding, has been tough, not just financially but emotionally.”

I’m sitting with Tim at a table crammed with the workings of organizing his father’s state funeral. It includes a huge cardboard box of condolence cards. The office-cum-sitting-room is encased with art: Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach, Max Beckmann, Margaret Preston, Melinda Harper, Deborah Russell, and on, artists whose work nods to the traditional practices of drawing and painting, post war and contemporary, the model that defines the personality-driven Olsen brand.

Tim has grown up with more art than most, his experience as a fledgling art dealer beginning with “The King of Queen Street” (Woollahra), the ebullient Rex Irwin.

“I loved having Tim as my Saturday helper, he made coffee, reminded me of people’s names,” says Irwin. “He was 18, charm on a stick, said ‘I know the smell of artists, been around them all my life’. He understands how artists like to be treated and that is integral to Tim’s success.”

Today, Tim’s warmth to artists carries through to his staff working in the gallery, its operations streamlined by his indomitable manager of 26 years, Katrina Arent.

Tim recalls the Irwin privilege of being able to work on a Henry Moore exhibition, of meeting Sir Alistair McAlpine, of cultivating relationships, “I came to understand the importance of a gallery maintaining quality and substance over fashion, of nurturing artists whose works will endure.”

Rex and Tim worked dashingly well together as Olsen Irwin from 2013 to 2017. “It is a beautiful space and a beautifully run gallery,” notes Rex who would front up to art fairs in his tartan kilt. “Behind the gallery was always the spirit of John and on every page of Tim’s memoir too is the spirit of John, a gregarious, charming host, a great raconteur who loved women as does Tim. Finally now Tim is a man alone. He has that extra responsibility and I am confident he’ll make a go of it.”

And while a New York gallery venture in 2017, Olsen Gruin, was stymied by Covid, Olsen is now forging ahead and gearing up to exhibit John Young at the Singapore Art Fair in 2024. Meanwhile the impressive line up for the Olsen 30th anniversary celebrations includes exhibitions from Warmun Art Centre, Mika Utzon Popov, and Louise Olsen, while Vivid is featuring John Olsen’s painting on the sails of the Sydney Opera House.

Tim was one of the initial founders of the 2008 Hong Kong Art Fair that became Art Basel Hong Kong backed by Tim Etchells. With self-effacing amusement, gallerist Tim talks of the struggle to sell abstract art to Chinese collectors, recalling his extravagant landscape analogies, describing Michael Johnson’s work as “reflective lights on Hong Kong Harbour”. By 2012 he had held a sell out stand at the fair of Sophie Cape’s feverish abstract paintings.

“Art fairs are a melting pot of venom, envy. People look at the Olsen stand and they are seething. It’s not because it’s a bad stand, it’s people thinking ‘who do you think you are?’ You’ve got to turn your back on the tall poppy stuff. I’m proud that I’m one of the few owner/director galleries that have survived this long, there are so many new galleries that are backed by corporate investors. This has made this game much more aggressive at the sacrifice of long term good will. The art world can be a nasty place, because the stakes are so small.”

There have been some memorable moments in the gallery’s history: “My father’s 2009 show Culinaria where he did paintings based on his favourite recipes. We made the catalogue into a cookbook. Jamie Oliver was in Australia launching his magazine so he came and cooked paella in the gallery with John. The following week Rick Stein opened the show – who could arrange that kind of serendipity… I’ve had a lot of luck. The one collector I was most taken aback by was when Paul Simon turned up with Brian Eno and procured a work while my son’s 6th birthday disco party was in full swing, I don’t think songs by The Wiggles was their speed, but fortunately it didn’t put them off. We talked at length about how music can be heard in art despite the silence. Buying the gallery on Jersey Road and adjacent terrace was a milestone, as was publishing my memoir in 2020.” In his memoir Son of the Brush, Tim talks about his alcohol addiction, saying, “Being sober in the art world is like being fully dressed at an orgy… You have to diversify your obsessions, to focus the appetite and now I have a sense that everything will take care of itself if I look after my side of the street.”

Tim holds an enormous amount of gratitude for what he has and works generously to enhance the quality of life for others. I wonder what his future holds. “I’ve spent the last five years driving to the Southern Highlands every weekend to look after Dad,” he says. “I’m thinking, why not make life more interesting? My son is in Oxford preparing for university. I’d like to be close to him. I’d love to open a space in Lisbon, chase the summers… I can afford to do that now.”

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 105, July-September 2023.