What to do with all that beauty?

Forging a new visual language, Pierre Mukeba is rewriting the narrative of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Words: Brian Obiri-Asare

In an ideal world, art should exist to tickle the senses, to play with emotions, and to send the spirit soaring on flights of limitless fancy. It should, through an alchemical blending of artistic quality and emotional content, enliven and enrich us all, right? But this isn’t an ideal world that we’re all mixed up in. Inequities and brutal paradoxes run rampant. Inscrutable structures and systems stifle a collective flourishing. No surprises then that art mirrors this beguiling state of affairs. Hype and trendiness elevate the mediocre. Gatekeepers choke out diversity. And despite often being aesthetically compelling, it’s common, all too common, for art that originates in the margins to be curiously absent from the spaces that matter. In such a context, it takes chutzpah, something Pierre Mukeba possesses in spades, to unabashedly insist on making work that “gives a documentation of African wealth and its rich, rich beauty.”

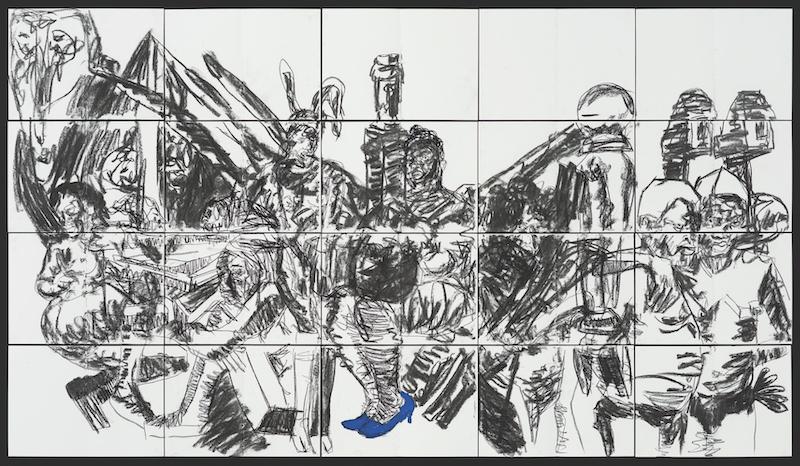

With paintings that serve as embodied meditations, figurative dreamscapes of intuitive acts of faith in form and line, hue and shade, material and texture, Mukeba has forged a mesmeric visual language. And with Max Ernst, Michelangelo, and Francis Bacon serving as important guides, these works help us tune into the presence of something else, something that sets us free from the miasma of the present. Accolades have come thick and fast and early – in 2017 he won the prestigious churchie National Emerging Art Prize, in 2019 he was a finalist in the Ramsay Art Prize. His works have graced the hallowed walls of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide and the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. In 2021 he held his first solo exhibition Black Emotion at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery in Sydney, which represents him, and later this year will follow this up with his solo exhibition Amri Kumi. This is no small feat for an artist still marked by his formative years spent in the war-torn yet minerally and culturally rich crucible that is the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“I want my work to be a bridge between myself and the wider public, a space where everyone can come and meet,” Mukeba tells me as he prepares for Amri Kumi.

A contemporary take on the ten commandments, this exhibition will be his most ambitious to date. By drawing sustenance from the Book of Exodus and its articulation of the Israelites’ journey, he aims to explore what young black people, whether they reside on the African continent or are scattered throughout the diaspora, witness and live through. One can expect vengeance, lust, greed, indeed a whole gamut of human emotion, to be given visual representation. The stance will be one of decided openness. “I want Amri Kumi to be both aesthetically and intellectually beautiful and open to whoever is willing to welcome the work” he says.

Amri Kumi will mark both a departure from and a continuation of Pierre’s work to date. The subject matter – an ongoing exploration of the nuances of the black experience – remains the same. So too does the unflinching portrayal of this variegated experience. However, in the wake of Black Emotion, where Pierre worked mainly with charcoal on paper, a new area of thinking has come to light. Using charcoal allowed him “to play with negative space and experiment with creating movement”. This freedom of expression also gave him confidence “to attack colours and shapes in a differ- ent way”. Perhaps most importantly though, it has cemented an outlook: “I now see myself as primarily a figurative artist.”

Amri Kumi will also see Pierre return to working with fabric in an intricate process that has undergone much development over the years. The process – a skilful layering of figures drawn on calico onto unprimed canvas – verges on the sculptural and allows Pierre to do what he does best: create visual stories bursting with sensuality. Aesthetic stimulation will again take primacy. The senses will be tickled, spirits enlivened, and challenged. There’s a generosity here. And a resolute sense of purpose. When I ask him how he imagines the public will interact with the work, Pierre takes a pause, “I know the sense of truth and beauty is what makes a work sing. I believe the public understands and is drawn to that.”

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 101, July-September 2022.