Robert Klippel: The Natural

A profound understanding of visual language coupled with a prolific artistic output makes Robert Klippel one of this country’s most highly acclaimed sculptors.

Words: Carrie Lumby

Over the past 40 years Robert Klippel has become recognised as not only one of Australia’s best known sculptors but perhaps the finest we have ever produced. In 1964 Robert Hughes was the first major critic to acknowledge Klippel as a superior figure in Australian art. The following year Daniel Thomas, in even stronger terms, followed suit. Since these powerful endorsements, the eminence of Klippel’s work and its significance in the history of not only sculpture, but of visual culture generally, has rarely been questioned, culminating in curator Deborah Edwards’ assertion in an obituary of Klippel that “he is comparable to some of the most important sculptors of this century”.

Having “neither peer nor imitator” puts Klippel in a somewhat unique position in his own country. Certainly, his oeuvre cannot be comfortably slotted into a linear tradition of Australian sculpture and its progressive developments. According to Edwards, curator of the forthcoming retrospective of his work at the Art Gallery of NSW, he is an Australian artist who would be better understood in an international context, in relation to such influential sculptors as David Smith.

Robert Klippel was born in Sydney in 1920, the son of Polish-English migrants. As a child he showed aptitude for constructing objects – model ships in particular – something he would later put to professional use as a model-maker at the Woolloomooloo gunnery (interestingly, now a contemporary arts centre) during World War II.

Like a number of artists with an intuitive vision and enduring faith in the power of the imagination, Klippel lasted only a year at art school, abandoning what he saw as the constraints of traditional formal training in favour of experiencing the ideas of art through his own self-directed investigations. This prompted a move to England in the mid 1940s. Here he lived and became a life-long friend and sometime collaborator with the pre-eminent Australian surrealist painter James Gleeson. During this period he also spent time in Paris, contemplating the constructionist works of Picasso and other modernist artists,5 as well as acquainting himself with André Breton and the French Surrealists.

After returning to Australia for several years in the 1950s he moved again, this time to the USA. Despite Klippel’s aversion to academic training in his own life, he became a teacher as well as a practising and exhibiting artist and in 1966 he was appointed visiting professor at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

From 1967 until his death in 2001, Klippel resided permanently in Australia. His close association with Sydney’s Watters Gallery, and the directors Frank Watters and Geoffrey Legge, began in the late 1970s and the gallery continued to represent him in Australia during his lifetime. He continued to work and exhibit prolifically during the last 20 years of his career – in the 1980s, for example, he executed more sculptures than his total output in the preceding 35 years. His final exhibition of metal sculptures was still showing at Watters Gallery when he died.

The driving conceptual force behind Klippel’s work, and an ongoing inspiration for the refinement of his sculptural practice, was his belief that the artist “should follow the example of nature and build in such a way that the final form will be as inevitable as any form in nature”.6 In particular, his personal artistic aim was to always “express the workings of nature – in the broadest sense”.

Taking as his starting point this enduring belief in the sculptor’s capacity to evoke the underlying structures of reality, by striking a subtle balance between organic and geometric forms – or in Sasha Grishin’s more lyrical terms, to “combine the energy and functionalism of the machine with the organic fluidity of a plant”8 – he always managed to rework this notion through the conceptual prism of the materiality of contemporary art and life. As Grishin has remarked: “Klippel’s vast and varied oeuvre challenged the very foundations of traditional thinking about sculpture.”9 He was “very much a man of his time”.10 This is evidenced through his openness to material experimentation; working with a variety of metals, wood, stone, clay, discarded industrial materials, as well as painted wooden and metal patterns. He also cast wax and plastic parts into bronze.

Klippel’s constant attempts to find more effective ways of constructing objects that articulated his desire to express the ‘static state’ in sculpture – that is, “those works which have a quiet, serene, timeless quality” – is also what drove his evermore thoughtful and analytical experimentation with ‘the language of forms’Indeed, throughout his artistic lifetime, Klippel developed a formidable conceptual vocabulary – a deep understanding of the elements of visual language. It is for this reason that Legge can claim Klippel to be “the Shakespeare of sculpture”. In an interesting historical aside, both were artists who died on their birthdays, something that Klippel’s partner, sculptor Rosemary Madigan, claims he would have seen as particularly appropriate – there was “a circular rightness about it”.

Klippel’s rigorous investigations into the play of the conceptual and the material resulted in a number of significant bodies of work. In the early 1940s there were two important developments in his practice: he made a break with figuration and began using found objects. During the 1960s his experiments with readymade materials extended to the utilisation of various discarded industrial materials and later in this decade he began casting wax and plastic parts into bronze from which he made sculptural assemblages from the disparate elements.

Another significant breakthrough came about in the 1980s when he began working with wooden foundry patterns originally produced as models for machines – parts that he had originally acquired in the 1960s. He used these patterns to cast a group of imposing bronzes for the Australian National Gallery’s Sculpture Garden. It also resulted in a prodigious series of painted wooden sculptures. Legge argues these works constitute perhaps his most important and resolved body of work. Certainly, they come closest to achieving Klippel’s aspiration to create serene, timeless, self-contained Buddha-like objects that successfully express “a delving inward to the inner workings of nature”.

A lesser known but nevertheless important aspect of Klippel’s oeuvre are his drawings and collages. Unlike many sculptors, Klippel’s drawings, while connected to the concerns of his sculptural practice, stand alone. He also executed a vast number of striking collages, often constructed from coloured paper. Christopher Chapman, a former curator in the drawings department at the National Gallery of Australia, describes the process of cataloguing his works on paper: “Klippel’s drawings are entirely experimental in their content and form. It is little known that his sketchbooks included designs for furniture and studies of marine life forms – all of which feed into his work as a sculptor.”

Klippel’s work is represented in the majority of Australian public institutions. In particular, the National Gallery of Australia and the Art Gallery of NSW both have comprehensive collections of his sculptures, drawings and collages. In addition to his work in the National Gallery of Australia’s Sculpture Garden, a bronze sculpture, commissioned by the South Australian Department for the Arts, is situated in the Adelaide Plaza, and James Fairfax presented a bronze sculpture to the City of Sydney which now stands outside the Museum of Contemporary Art.

For an artist of his stature, Klippel’s work after his death has not succumbed to the Howard Arkley phenomenon. There has been no sudden indiscriminate scrambling for any works on the secondary market. As a result, collecting Klippel is still a commercially astute decision. Sydney’s Watters Gallery is a good place to start. As long-term professional associates and friends of the late artist, the directors Frank Watters and Geoffrey Legge have the necessary expertise to introduce potential collectors to Klippel’s work. Melbourne’s Australian Art Resources also became primary dealers of Klippel recently before his death. They have spent the last three years meticulously cataloguing Klippel’s bronzes.

Immediately after his death they sold four significant bronzes for around $100,000.

There is also the chance to acquire the work via the secondary market. For example, recent sales at auction include the Christie’s sale of a steel sculpture for $46,000 in late 1998 – the highest price for the auction house’s sale of Klippel to date. Lachlan Henderson of Christie’s sees Klippel as a great investment but notes that his bronze and metal sculpture is more in demand than his timber works. He also makes the point, in concert with many experts on Klippel, that the fundamental problem with the commodifiable dimension of his work is that it’s sculpture, a visual form that has never reached the prices in Australia that it does overseas. It is on this basis that Klippel’s workremains relatively undervalued.

Prices for Klippel’s sculptures are still affordable, and currently sell for around $8,000 for a small wooden assemblage and up to $500,000 for large bronzes. His equally collectable drawings and collages are modestly priced from $2000 to $40,000. Foran artist with such a formidable reputation and arguably a notable place in international art history, Klippel’s works remain a good investment, and seem likely to continue to increase in value for a long time to come.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 21, JUL-SEP 2002.

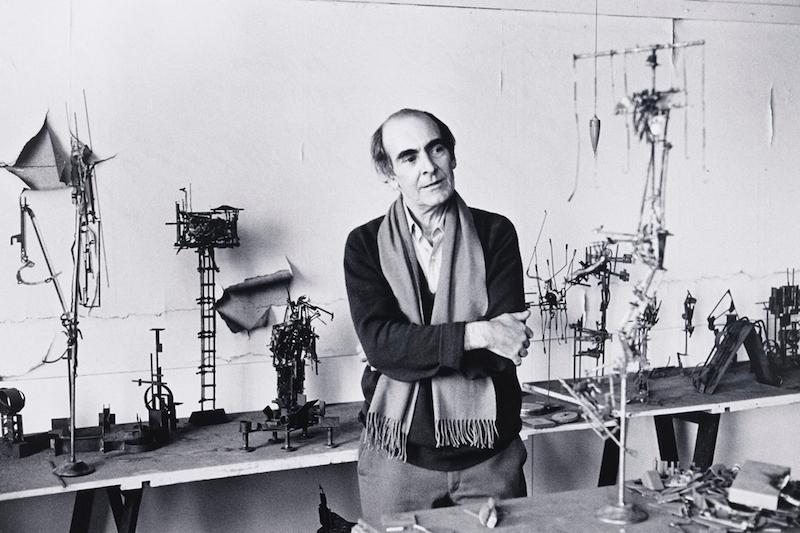

Image: Robert Klippel, 1979 by David Moore, gelatin silver photograph, selenium toned (56.0 x 51.0 cm), courtesy National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, Australia