Dale Frank: A New Sorcery

Dale Frank’s work, he justifiably declared, is “out there, all on its own…majestic and strange.”

Words: Edward Colless

Photography: Jon Reid

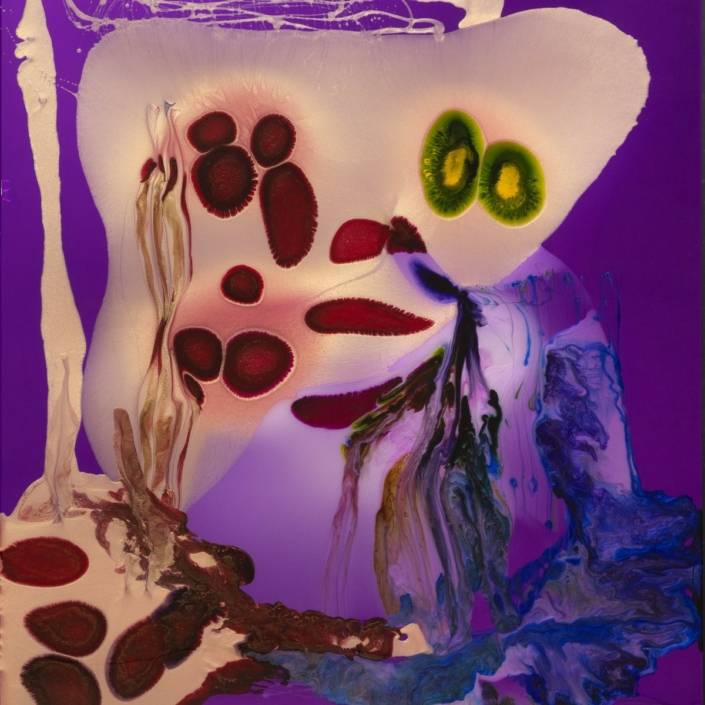

Words fail us when confronted with Dale Frank’s art: especially simple words, like “painting” or “sculpture”. And our encounters with Frank are indeed always as confrontational as they are captivating. In his relentless experimentation with — and exploitation of — sumptuous chemical, physical and optical detonations of substance and shape, of surface and volume, of mass and speed, he has wildly distended and disintegrated these two bland descriptors and long left them behind. And that’s even when still using familiar or traditional materials and display protocols of paint or of sculpture. A few years ago, art critic Andrew Frost admitted to being momentarily at a loss for words when asked by a young art student to “account for Dale Frank in relation to recent theories of painting”. Frank’s work, he justifiably declared, is “out there, all on its own…majestic and strange.” But its contemporaneity could be grasped with an idea that had been percolating through the avant-garde since the mid-twentieth century, an idea given theoretical and critical definition in the 1970s and that has assumed currency again today. Think of Frank’s work, advised Frost, as “expanded painting”. It’s a piece of art jargon, true; but it’s a good one when trying to assess Frank’s frequently astonishing mutations of artistic technique. For anyone un- familiar with the legacy of this term, picture the experiments in expanded cinema” — precursors to the contemporary VJ’s armory — which broke apart the economic and formal proprieties of theatrical screening with 1960s lightshows and happenings. Ambient multiple projections of found or abstract footage montaged, collaged, corroded and incorporated into live musical and dance performance, like a deregulated mode of opera or ballet. It fits, yes?

In its milder usage, the adjective expanded can liberalize a medium otherwise delimited to activities with, say, oil or acrylic and canvas even by just adding tools like sticks, mops, buckets or by using a bicycle or human body for a brush; or using car duco or blood, food or excrement for paint. Painting for instance can expand into neighbouring subcultural zones, such as tattooing or graffiti, and adapt their aesthetic skills and values; sculpture can momentarily annex industrial or urban or garden design. But there is also an inflationary ambition in this term that looms when both expanded painting and sculpture don’t just break down their disciplinary borders in trade and trade-off but also territorialize their environments (architecture, landscape, cyberspace, museum, art market)—and, ironically, when the inverse happens. In this respect, the expanding field of painting or sculpture aspires to a “supercultural” systemic state, a kind of denatured ecology. This is not the same as the modernist vision of a “total work of art” which was a harmonious synthesis of media, amalgamated and integrated in the functions and aesthetics of a wall, a room, a building or a city. Instead, this mode of expansion assumes a higher dimensional state than any such localized spaces. And this inflationary expansion of a medium is not necessarily benign; it can be catastrophic. It is not a raid or a trade; it is a blitz, a supernova.

We need both senses of “expansion” to handle Dale Frank’s art.

He might justifiably proclaim that the word “art” is the single suggestive sublimation for all his miscreant and marvellous objects and deeds, and the mad or diabolical experiences they offer us. Even then, we’re still struck by the need and the compulsion to find words to account for what Frank manages to do so surprisingly and fluently with his materials, with medium and with meaning. We have to resort to far more complex, nuanced and yet I’d say also hyperbolic language to cope with his characteristic profligacy and with the prodigal, maverick shape-shifting and ebulliently mongrel stylistic frenzies that twist and tunnel and gallop and swagger throughout over thirty years of unstoppable and aberrant creativity.

Frank’s art is immodest, defiant and extravagant— usually igniting in a compound of bristling mockery fused with exultant virtuosity—and it warrants these qualities in any response worthy to it. Recall his darkly surrealist, epically automatic and fetishistic drawings in the 1980s, which were forged from overlaid linear whorls that staked out sinewy contour lines of monstrous masks and bodily organs. Think of the viscous deluges and haemorrhages of iridescent and opalescent varnish slithering like threads of saliva or swelling in tumescent and tumorous globules in the paintings of the past decade or so. Across this career Frank’s visual idiom is irrepressibly febrile and luscious…and corrupt. We might be tempted to judge his taste for lurid, dazzlingly synthetic colour combinations (and their glut of kitschy associations with disco psychedelia and casino hotel décor) as indulgently decadent. But, contrary to what might seem to be their slick ambience, these are not representational works of art, not even by association with the glossy materials of Pop glamour, glitter or licentiousness.

We might be tempted too to think of the surges, blooms and dribbles of the varnish paintings, with their notorious drying times, as punk or recklessly accidental (some still drooling or drooping down to the floor years after being acquired). But no matter how spontaneous or buoyantly serendipitous the activity, the agility of execution and conception in almost all of Frank’s work demonstrates indisputable finesse and intuitive control that’s only won through dogged and deep experimentation, even if much of that seems like daredevil trial and error. And it has to be noted that Frank’s paintings don’t deferentially dry in the air, with that insinuation of a domestic process—they liquefy like magma, they incandesce and stun like plasma, swarm and bustle like an infestation, condense with the murky threat of a viscous miasma, they warp, set, congeal, adhere, they harden. That’s to say, these works are phase changes of matter and energy, abstract but also literal, and customized under the exertion of nonstandard physical forces: a kind of sorcery. The most recent interactions of resin goop, vast veils of blood, scattered crystals, liquid glass and Perspex can be—in the studio—as dangerously explosive as an inspired unholy Promethean science con- ducted in a gothic castle tower. These are conjurations of a dark cosmological catastrophe in a fierce mirror that dazzles with a vision of demonic glory.

LARA NICHOLLS Assistant Curator of Australian Art National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

“My first encounter with a Dale Frank work was in 2001 and I immediately acquired it. What first compelled me was colour, then surface—an oozing viscous globular medium that seemed to be arrested in time. There was also an ‘endlessness’ inherent in the work which gave it a very contemplative aura. People really respond to Frank’s work largely because of its sensory quality. Basically, they are lovely to look at—mesmerising and tantalising, and so we become engrossed in their open-ended vision.

“The breadth of Frank’s practice is also compelling. He never stands still in one zone, but has been able to create a body of work that, while having some integral threads, is a wide-ranging practice. He has always been a colourist but his latest work takes colour to a new level. We are more immersed in the space of the installation than ever before, and there is a return to the narrative quality seen in his installation at Cockatoo Island for the 17th Biennale of Sydney in 2010.

In 2014 I managed the accession of a large body of Frank’s works by the National Gallery of Australia. Above all, this experience highlighted the ongoing experimental nature of Frank’s practice, from the earlier drawings of the 1980s, collages of immense detail and skill, assemblages, linguistic works that yell out word plays and expletives at the viewer, and works that are the result of trans- mutation and chemical reactions such as burning plastic bags to create filigree layers. It shows that the later oozing pigment and varnish works, for which he is so well recognised, are just one chapter in the ongoing narrative of Dale Frank’s mysterious universe.” – Paris Lattau

ROSLYN OXLEY Director Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery has been representing Dale Frank since 1982, as he emerged as one of Australia’s most exciting and dynamic contemporary artists. Since then, Oxley says, Frank’s practice “has been unfailingly vigorous and extraordinary. He is without a doubt one of the most highly regarded painters of his generation.”

Frank also has a longstanding international significance. Oxley believes this is in part due to “his theoretical approach to painting as well as his manipulations of the medium, testing the technical, conceptual and perceptual limits of his materials. He is the leader in the field of experimental progression.” Despite what Oxley calls his “long- standing exploration of forms of painting,” Frank’s trans-avant-gardist commitments have also moved him beyond the traditionally defined limits of the medium. As Oxley points out, this has included experimentation with the forms of installation, performance and sculpture.

No doubt the exploratory breadth and sheer prodigiousness of output has contributed to Frank becoming one of Australia’s most collected and prized contemporary painters. For Oxley, his longstanding practice is “widely appealing and always unexpected—engaging for every collector.”

Those who closely follow Frank’s practice will know that this has seen his prices consistently increase to reflect national and international demands. “His work tracks extremely well throughout his career. From each body of work he consistently sells to major collections,” says Oxley.

For Oxley, however, Dale Frank remains a dynamic and exciting contemporary artist because he “does not rest on his success.” “He is always inventive and pushing the boundaries conceptually.” And it is the element of surprise that continues to keep collectors, curators and the art market intrigued. – Paris Lattau

Dale Frank exhibits with Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland, Neon Parc Gallery, Melbourne and Pearl Lam Galleries, Hong Kong. Dale Frank will be exhibiting with Neon Parc from 30 June – 12 August, 2017 in Melbourne and with Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney at Sydney Contemporary from 7-10 September, 2017.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 81, JUL-SEP, 2017.