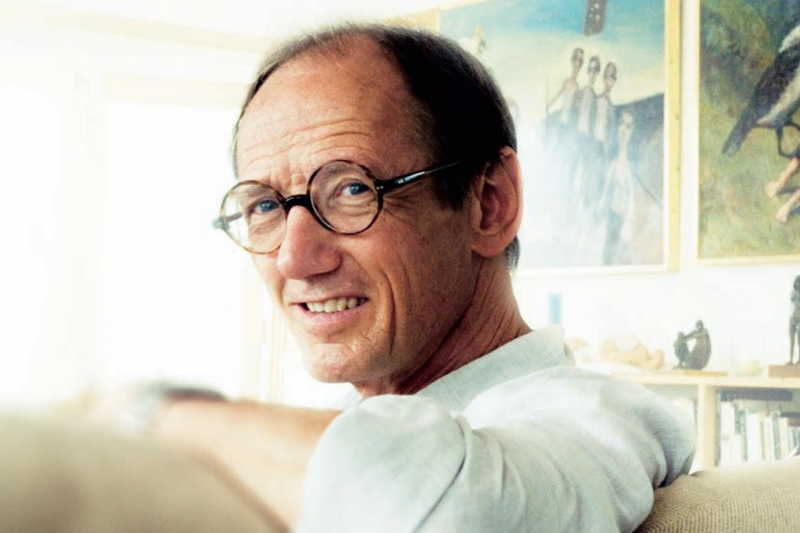

Garry Shead: Gentle Lyricism

For a while there Garry Shead lost favour with the art establishment when he deliberately didn’t get swept up in the trend toward abstraction that was dominating Sydney at the time. Today he is widely regarded as Australia’s finest living lyrical figurative expressionist painter.

Words: Sasha Grishin

Biography

Born in Sydney in 1942, in Garry Shead’s childhood his uncle the winemaker Maurice O’Shea and his friends who included William Dobell and Hal Missingham, were a major influence. One of his fondest childhood memories is when he was awarded the Argonauts’ Art Prize – the judge was Jeffrey Smart. Last year Smart told me that he could still remember the naïve excitement of that painting.

He received his early schooling at Shore in Sydney where the art master John Lipscombe and the art teacher, Ross Doig, were both supportive of his artwork and annually he won the school art prize. In his final year at Shore, he produced his own satirical newsletter, The Corn Flake, which had a legendary popularity with his peers.

In 1961 Shead gained admission to the National Art School (NAS) in Sydney and that year he started to shoot his first 8 mm experimental film, Ding a ding day, with borrowed amateur camera equipment and employing Martin Sharp and Richard Neville in leading roles. It took another five years before this 10-minute film was completed. Also that year, his painting of his sister Lynne was accepted and hung in the Archibald Prize exhibition, at 19, making him one of the youngest Archibald exhibitors ever. Simultaneously he commenced work as a cartoonist for a number of magazines including The Bulletin.

At the NAS Shead formed friendships with Martin Sharp, John Firth-Smith and Ian van Wieringen. In April 1962 the first issue of The Arty Wild Oat was published as the official journal of the National Art Students Club, with Garry Shead as its Editor, Martin Sharp as Assistant Editor, John Firth-Smith as Pictorial Editor and Sue Woods as Women’s Editor. The first issue featured on its front page an interview with the art critic Robert Hughes, while the second issue, which also turned out to be the final issue, carried Shead’s interview with Norman Lindsay.

Shead’s earliest art school work focussed on the female nude found in urban and rural settings. Although he spent two years at the NAS, he is basically a self-taught painter who spent many years studying the works of the Old Masters and various manuals and handbooks on art. Jeffrey Smart and David Strachan were two of his early mentors in art school, while Rembrandt, Velazquez, Vermeer and Dalí were four of the masters from whom he learnt the most about the art of painting. Even at this early stage there is a certain conceptual unity in all of Shead’s work – the paintings, drawings and the films have a common erotic quest and gentle lyricism.

Shead appeared as a guest cartoonist in The Bulletin in August 1961, then in Honi Soit, The Sydney Morning Herald and, with the founding of OZ in April 1963, became a regular contributor. His freelance cartoons, apart from providing a source of much needed income, also brought him into contact with art critics and the broader world of Sydney journalism. It was also in the context of The Bulletin that Shead published an article which, at least in his mind, led to his non-re-admission to the NAS for his third year of study in 1963. Titled Teaching artists how: The Power game, Shead argued emotively that the facilities and the teaching at the art school were antiquated and inadequate.

It was also at about this time that he painted a bold and expressive portrait of Richard Neville, 1964/65, as a delicately pink nude, slightly splayed out, in the manner of the art brut images of Dubuffet. It is an immediately engaging image and it attracted the attention of Daniel Thomas, who was then both a curator at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and an influential critic. Thomas noted in an encouraging letter to Shead: “Tony Tuckson had apparently noted it with admiration in January long before I’d seen it and Jack Lynn was just as impressed.” Thomas several months later introduced him to Frank Watters, of the Watters Gallery, where Shead held his first solo exhibition in July 1966. He has subsequently had over 45 solo exhibitions and has participated in over 200 group exhibitions.

While Shead has been interested in the writings of DH Lawrence for four decades, and at one stage he reinterpreted in his art a number of Lawrence’s paintings, it was only after 1987, when he and his wife, the sculptor Judith Englert-Shead, moved to Bundeena, that he thought seriously about a major series of works related to Lawrence’s novel Kangaroo. Bundeena was similar to Thirroul, where Lawrence wrote his novel and which Shead had been visiting since the early 1970s. Shead’s DH Lawrence series of the early 1990s appeared as a single breath of creation, as he later observed: “Everything just flowed, I didn’t have to push anything … Once the eyes started looking out, that’s when the paintings became alive, they got a dynamic to them.”

The brilliance and success of this series in part reflects the richness of the associations which it evokes. Set within the recognisable Australian coastal scrubland, the paintings neither narrate episodes in Kangaroo, nor the experiences of Lawrence and his wife Frieda in Thirroul, but create a rich and ambiguous fabric of vision. They are wonderfully vivid allegorical paintings. The ubiquitous kangaroo and the voyeuristic magpie which occur in many of the works may refer to what Lawrence termed the strange “invisible beauty of Australia, which is undeniably there, but which seems to lurk just beyond the range of our white vision”.

With the Royal Suite series of paintings of between 1995 and 1998, the historical reference may be to the white goddess of Australia and the visit of Queen Elizabeth II in 1954, but the paintings touch on a much broader frame of reference. The queen, accompanied by her lecherous consort, encounters Blinky Bill koalas, emus, kangaroos and ceremonial Aboriginals, while she knights merino sheep on red carpets before her wide-eyed subjects. The series may be interpreted as part of the republican discourse, a post-colonial critique of British occupation of Australia and the reconciliation movement with our indigenous peoples, but also in part it expresses our yearning to believe in myths and fairy tales.

The Dancers series, which first appeared in the mid-nineties, as well as being a direct reference to the act of dancing, also serves as a metaphor for the dance of life and the path which a couple must negotiate through life’s journeys. It is as much about love and tenderness, about passion and desire, as it is about voyeurism and erotic wish-fulfilment.

His most recent Ern Malley series is a culmination of several years of thinking and artistic experimentation inspired by the poems of Australia’s most enigmatic poet. While it has been argued by some that Ern Malley and the 16 poems which comprise The Darkening Ecliptic are simply a literary hoax designed to discredit modernism, Shead through his paintings, drawings, collages, etchings and ceramics argues that the poems are greater than the conscious petty intrigues of their authors and have created in the Australian psyche the image of the creative individual and his precarious path in a materialistic world. These are some of his most wonderful and evocative paintings to date.

In 1993 Shead was awarded the Archibald Prize and in 2004 the Dobell Prize for drawing, which was judged by John Olsen.

The Best Works and Where to Find Them

Garry Shead’s best work starts in the early 1990s with the Kangaroo D.H. Lawrence paintings; then the Royal suite, The dancers, The artist and the Muse and more recently the Ern Malley paintings. Australian Galleries represents Garry Shead in Sydney and Melbourne, Philip Bacon in Brisbane and Paul Greenaway in Adelaide. With recognition, Shead’s prices have grown dramatically in recent years and at present at exhibitions his oil paintings range in price from $165,000 to $330,000. Most exhibitions sell out quickly.

Prices at Auction

While Garry Shead’s work appears frequently at auction, generally it has been the small oils or works on paper and not the huge recent major paintings which have achieved top dollar prices. His modest size canvas The dance sold at Lawson-Menzies in 2003 for $143,100, while another relatively small canvas, The secret, sold at Christies in 2003 for $129,500. Generally Shead’s work has not as yet had a major presence in the secondary market.

How to start collecting

Shead belongs to that group of figurative artists who included his friends Brett Whiteley and Martin Sharp, who were not swept up by the trend towards abstraction which was dominating the Sydney art scene. Like them, Shead initially found more favour with the public, than with critics, curators and the institutionalised art establishment. He is a brilliant and expressive printmaker and his etchings can be acquired through his dealers generally under $3,000. His drawings are still relatively modestly priced, starting at $4,400, but generally achieve higher prices at auction. The oil paintings are expensive and are likely to appreciate. Sasha Grishin’s Garry Shead and the Erotic Muse (Craftsman House, 2001) reproduces and discusses much of his work. •

Garry Shead’s next exhibitions will be held at Greenaway Art Gallery, Adelaide and Australian Galleries in Melbourne and Sydney, dates to be confirmed.

This issues was originally published in Art Collector issue 40 APR-JUN, 2007.