In The Works: Visual Arts 101

Visual arts 101: lessons in influential artworks and their significance.

Words: Edward Colless

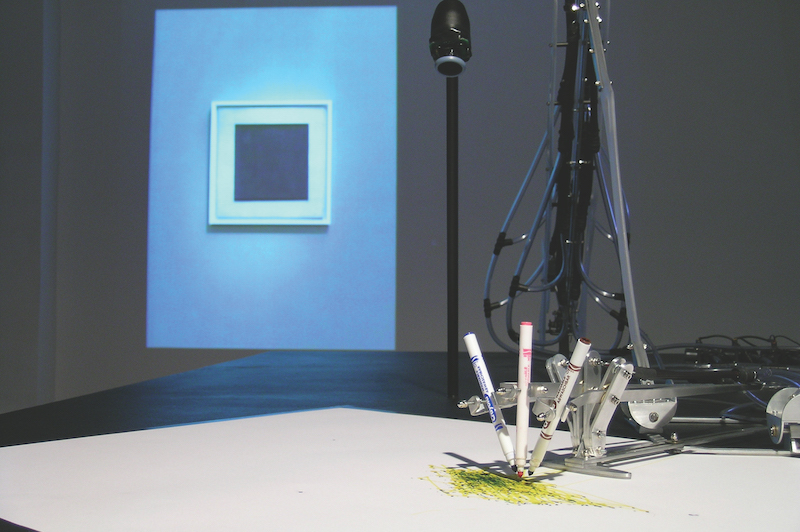

BACK IN THE PREHISTORY of the World Wide Web, in a 1969 interview in Playboy, the media theorist Marshall McLuhan prophesied that electronic media – which he called an extension of the human central nervous system – could soon create a “universality of consciousness”, and that one should “expect to see the coming decades transform the planet into an art form”. We have certainly witnessed daunting vectors of terraforming since McLuhan’s prophecy; although whether climate change, the geopolitics of globalisation, and the platform capitalism of the Web 2.0 could be called art forms might be arguable. But in 2002, with no less oracular insight, the international bio-art syndicate SymbioticA (among other feats, known for growing Stelarc’s grafted third ear) produced, or activated, an experimental work of art that invoked the darker 21st-century glob- al dimension of information technology. In a small crypt-like basement room at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image in Melbourne, two articulated robotic arms – driven by electrical and hydraulic musculature that theatrically clicked and huffed – nervously stretched and contracted across a clinical slab to draw abstract doodles on a large sheet of paper. These enigmatic sketches looked as if they could have been done in Kandinsky’s studio; or, alternatively, by a child in kindergarten.

Guiding these squiggles was something very strange, and still today quite disturbing to consider. Sensors recorded the presence and movement of human traffic in the room, the signals of which were transmitted by internet to a neuro-engineering laboratory in Atlanta in the USA, where they were fired into a vat containing a cultured biomass of nerve cells. Behaving like a brain, this organ then reacted to the electrical stimuli, sending its own electrical impulses in real time response back to the room in Melbourne, where these triggered movements in the device’s insect-like limbs. The drawings were in fact intimate and specific portraits of the gallery visitors who, entering the room, encountered the sensory organs of a planetary-scaled nervous system. It may have had a rudimentary brain, but this bio-cybernetic artist (SymbioticA called it “semi-living”) was evidently observant.

Was it also sentient? Did it have any consciousness of its servitude as a ghost in the shell, of its imprisonment as an entertainment to the gallery visitors? Was the art it produced merely like the gestures of a Ouija board in which we playfully entertain a voice from the “other side”, or like a Rorschach blot in which we therapeutically confess to our unconscious wishes? Perhaps those marks were the scribbling of an interred Dalek-like neuronal organism gone mad. Or, more threatening and promising, the early steps of an AI’s infantile stage when learning to communicate with the world: messages in the arcane language of an altogether exotic creature, signalling the incarnation of a new species.

It’s appropriate to revisit this extraordinary work of art today with the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The aesthetic as well as ethical quandaries of Shelley’s Promethean gothic hero are vividly resurrected in this work, as is the pathos of his vivisected and re-animated creature. (The brain of the work, for instance, had to be terminated after the exhibition, by turning off the life-support mechanism that fed it.) But perhaps the most beguiling visionary aspect of SymbioticA’s work is embedded in its strange title: MEART. That monstrous hybrid of “meat”, and “art” also contains “me”. Could this not be a premonition of the tentacular cyborgian sprawl of social media with its ubiquitous sensory organs track- ing every human movement, and paying us off in the global currency of the selfie?

Image: Guy Ben-Ary, Phil Gamblen, Oron Catts, Steve Potter and Douglas Bakkum, MEART, 2002. Installation view. COURTESY: THE ARTISTS. PHOTO: PHIL GAMBLEN.