Maria Kozic: Pop Go the Weasels

Critic Adrian Martin argues that Maria Kozic’s intense rendering of pop art escapes the pigeonholing of both radical and conservative critics…

Words: Adrian Martin

In the recent art-and-essay video documentary Negative Space, the British filmmaker Chris Petit (Radio On), armed with his modest, hand-held, digital camera, cruises the highways and byways of America looking for one of his cultural heroes, iconoclastic movie critic and painter Manny Farber. At some point along the way, he pulls in as a guide to this terrain the no less irascible art historian, Dave Hickey, author of Air Guitar: Essays on Art and Democracy.

Hickey spins a good, loving line on pop art – one of the great forms of 1950s and 60s culture that indelibly formed his sensibility. He quotes the observation of his famous friend Peter Schjeldal about the weirdness of a huge Roy Lichtenstein canvas (the one that basically blares out the word ‘Wham!’ in vivid, eye-popping colours, in a stunningly simple but dynamic graphic design) finding its home in London’s Tate Gallery. “The Brits just don’t get it!”, roars Hickey with glee, as he puffs frantically on his cigar and curses up a storm. “It’s just – ‘Wham!’ That’s all it is, right there in front of them!”

No matter how long Hickey’s imaginary Londoners (a dour lot) stand there, trying to decipher the significance, the gesture, the political context involved in that ‘Wham!’, they will never get it – the pure fact, the pure sensation of it. Lichtenstein’s painting need not even be considered as ironic or cheeky, or a further blow in that endless, fruitless campaign to reconcile, once and for all, high culture with low art. Or, at least, it shouldn’t be considered only, or primarily, under such lights. Whatever such pop art does to our relative and ever-changing sense of values, it does so in a time and space at one remove from the emotional immediacy and sensuality of the work.

I experienced that wham-like shock of immediacy the first time I clapped eyes upon Maria Kozic’s Crush series in the mid-1980s. These large, vividly red canvases, renditions of amorous clinches drawn from various classic Hollywood movies, like From Here to Eternity, were way beyond the petty intellectual games and debates that had surrounded the Australian neopop and popist art of the early 1980s. I knew instantly, as I took in the plaintive force of these Crush paintings, that the newly forged postmodern rhetoric of pop – all that talk of ‘second degree’ art, of quotation and displacement and cultural context – was just clutter, at best a pretext, and at worst an impediment to appreciating this amazing new work by an artist I had admired since her art school debut in the late 70s.

As Kozic’s reputation and achievement grew both in Australia and abroad (she now resides in New York), one heard the inevitable scurrilous, suspicious rumours that surround any local tall poppy of real note: that her art was based on the latest thing displayed on the cover of express-posted copies of Flash Art; or that it was cooked up with a gang of co-conspirators (mainly male) in a microwave oven of new-fangled critical theory, as if to opportunistically provide handy illustrations for the newest artspeak.

But Kozic’s art has always forged itself on a different level entirely. Her work is boundlessly clever, witty and inventive – but has nothing to do with the urbane puzzlings of recent art theory. It is conceptual, but always direct – like Lichtenstein’s Wham! – drawing upon and enacting a wide range of sense perceptions, bodily memories and emotional torrents (sex and violence are big topics in her work). Above all, it is intense – at times scary to the point of being overwhelmingly horrific; at other times unexpectedly placid and poetic, reminding us of the deep and unforced childlike qualities in her sensibility. Kozic’s art is logical and precisely realised to a fault; but it grows from intuitions, dreams, impulses and visions both everyday and subterranean.

Kozic will forever be associated with pop art and pop culture. Historic (we might even say classical) pop art inspired her with its ethos, its directness, its vivid palette, stylish framings and ingenious transformations of ‘found’ material. Pop culture – of which she is a voracious and passionate connoisseur – is the air she breathes, her lifeblood: from midday TV Hollywood movies to the paroxysmic heights of Japanese toys, manga and anime, Kozic is perpetually enriched by the shocks and delights of the new. In the wake of Warhol, she embraces commercial commissions for the artistic and material possibilities they enable – the opportunity to work in every imaginable visual and sculptural medium from the smallest (a postage stamp) to the largest (an inflatable logo-toy atop Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art), via posters, t-shirts, record covers, installations…

Although Kozic’s links with pop art and pop culture are real, avowed and vital, I wonder sometimes whether such reference points do not simply serve to put up fussy, unnecessary barriers between audiences and her work. At the risk of broaching polemics, I think it is necessary, in order to clear a path before Kozic’s singular gift, to take the pulse of the whole critical-educational scene surrounding and often limiting the appreciation of Australian art at present. For, if any of us experience vague stirrings of discomfort or trouble as we take in Kozic’s prolific work, it is essentially because of the way we have been prodded to worry, in grand and lofty terms, about the contemporary situation of art and culture in general.

And here I will need to take on not the underground, art-school theorists who once ‘problematised’ Kozic’s art to the nth degree, but those above-ground commentators and reviewers who today grumpily eye her work from a high moral and aesthetic ground.

One of the most common lines of assault in contemporary art reviewing is to ascribe to a work or an artist a high-flown intention, and then to mock the result for not living up to this intention. This two-step punch is the common manoeuvre uniting art conservatives of all stripes from Giles Auty to Peter Timms. It is modern art that especially invites this mauling, since impossibly inflated aims – drawn from the language of radical politics and theoretical philosophy – can be so easily attached to it (thanks largely to the earnest but not always elegant or lucid scribblings of curators and catalogue writers).

Conservative critiques of this sort typically proceed via formulations like: ‘This artist wants to destroy the institution of art, but his work is bought by galleries and he wins awards and receives grants’; ‘This piece bathes in the open-ended, anything-goes ethos of postmodernism, but it fails to reveal a multiplicity of meanings’; ‘Contributors to this group show aim to subvert all forms of western representationalism and logocentrism, but yet they are still painting on canvas and giving their works solemn titles’.

Such reactionary reviewing is a form of shadow-boxing: it scarcely requires the presence of the artwork itself. It is more theoretical – more dependent on signs, fictions and abstract concepts – than the theories it so mercilessly derides. All its practitioners need is the merest indication of an abstracted gesture arising from the artwork, something that triggers an appropriately apocalyptic alarm bell in the head of the ever-vigilant, hyper-sensitive, cultural-watchdog critic.

So, in place of attempts to describe, decipher or enter into the spirit of an artist’s expressive register, we read trigger-happy attacks on fashionable theorems, politically correct platitudes, and institutional artworld follies (all of which, let it be said, do indeed circulate in abundance). And, of course, contemporary art, thus reduced, vaporised into mere cliché and evacuated of any possible sense, is in the same breath decried as reductive, vague, empty of meaning…

There may be no mode of art more prone to this kind of feeble critique than pop art, in all its diverse historical manifestations. The easiest way to disable such art – armed with a few ringing, choice quotes from Jean Baudrillard’s early 80s piece ‘Is Pop an Art of Consumption?’ – is to punch up that same old song on the art-review jukebox: ‘Pop aims to parody and subvert the ersatz products and manipulative tricks of a filthy consumer society, but it itself becomes a mere artworld commodity, aping what it seeks to criticise’.

Warhol’s eternally plain, stony-faced retort to such rhetoric – that pop was more about ‘liking things’ in our crazy, new world, rather than decoding or destroying them – has never quite served to disarm those commentators who have their anti-pop defences and prejudices built wall-high. Sometimes, in fact, it seems that nothing even halfway simple about pop can be advanced in public – since one of the more regrettable legacies of the artworld follies of the 1980s has been a proliferation of ironic and counter-ironic moves, nothing ever offered or taken without intense, hermeneutic suspicion (commonly known as paranoia).

Pop’s simplicity – its inventory of loves and hates, methods and obsessions – is immediately converted into a Byzantine cultural politics of simulacra and masquerade, a furious square-dance where values of authentic and counterfeit never stop whizzing around each other long enough to settle into any comfortably identifiable place. Lichtenstein’s direct ‘Wham!’ is suddenly more obscured, more veiled than ever. And the intensity of Kozic’s art is fudged, overlooked, abstracted into some comment (subversive or complicit, depending on your politics) upon consumerism or gender stereotypes or media-induced desensitisation… in the end becoming, far too often, just a pawn in a zealous game between those who wish to espouse or promote current art theory, and those who wish to unmask or outflank it.

The French cinema scholar Nicole Brenez (curator of experimental film for the Cinematheque Française) states plainly in her recent essays a higher, contrary principle that has too often been lost (if it was ever grasped) within the Australian art scene: art is always in advance of theory, always leads it. Today’s cutting-edge art is always finer, more complex, more mysterious in its moods, moves and effects than yesterday’s critical theory can allow us to immediately gauge and express. This is true even of a form like pop art, which can appear these days traditionalist in its mining of familiar materials and tropes. And it is especially true of the art of Maria Kozic, which perennially leads its viewers into a new world by way of shocks gentle and violent, provocations exact and disarming, revelations sweet and profound.

COLLECTING KOZIC

Maria Kozic, the 42-year-old Melbourne-born multimedia artist, has produced a large body of work that includes sculptures, paintings, films and videos as well as large-scale installation pieces. She has also released CDs of her music collaborations with Melbourne cultural identity Phillip Brophy and produced short-run magazines such as Things, T.I.T.S. and Dynamite. Her work draws inspiration from ‘trash culture’ such as comic book illustrations, cult films and pop music. As an artist, Kozic’s allegiance is to no single medium, but to a pop art sensibility.

Kozic, based in New York since 1995, first came to prominence in 1978 as a member of Tsk Tsk Tsk, a music, performance, film and visual art collective. Kozic was also producing her own work and was featured in influential exhibitions such as the National Gallery of Victoria’s seminal Popism show curated by Paul Taylor. Kozic’s work had also appeared in the 1981 Biennale of Sydney and by the time of the inclusion of her work in the 1986 Venice Biennale as part of the Aperto section, she had emerged as one of Australia’s leading contemporary artists.

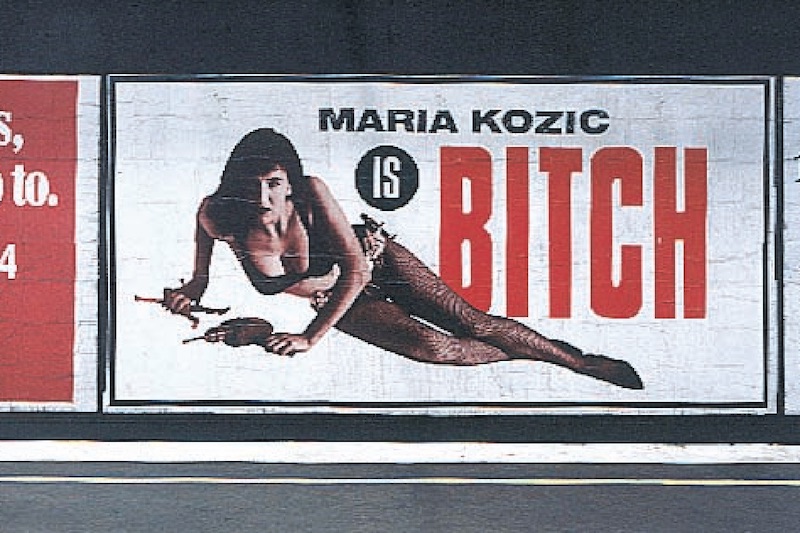

Although Kozic is often associated with Australian art of the 1980s, some of her most ambitious projects have been executed in the 1990s. Wolf Pack, an installation of papier-mâché wolves exhibited in Australian Perspecta 1991 at the Art Gallery of NSW, was an audience favourite. Its combination of a populist sensibility with theatrical lighting and sound effects was a neat distillation of Kozic’s aesthetic. Other projects in the 1990s such as her Blue Boy inflatable from 1992, installed on the roof of the Museum of Contemporary Art, and her provocative Maria Kozic Is Bitch posters mounted at locations around inner city Sydney and Melbourne in 1991, were playful and media savvy. Blue Boy was part of the Birth of Blue Boy exhibition and the street and railway posters promoted her Bitch series at City Gallery in Melbourne and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery in Sydney.

Kozic’s canvases command prices around $3,500 through her two Australian dealers, Anna Schwartz Gallery in Melbourne and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery in Sydney. In the secondary market Kozic has been under-represented. Works from the 1980s, Clutch I, II and III, (1984) sold at Joels in 1993 for $1,650. Two years later, Lichtenstein Dot, a key early work from 1986, achieved $1,380 at Sotheby’s June sale in 1995. Although only three works have been offered at auction (Meow, a screen print from 1983, sold for $220 at Joels in 1995) all were sold, albeit at modest prices. With the presence of contemporary art at auction on the rise, it would appear that work by Kozic represents an opportunity for the astute investor.

Kozic’s work has been acquired by public galleries including the National Gallery of Australia, the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Queensland Art Gallery and the National Gallery of Victoria. Her work can also be found in private and corporate collections such as the Loti and Victor Smorgon Collection of Australian Art, and Artbank.

New work by Maria Kozic can be seen at Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne, throughout December.

-Andrew Frost

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 10, OCT – DEC 1999.