Matthys Gerber: With Flying Colours

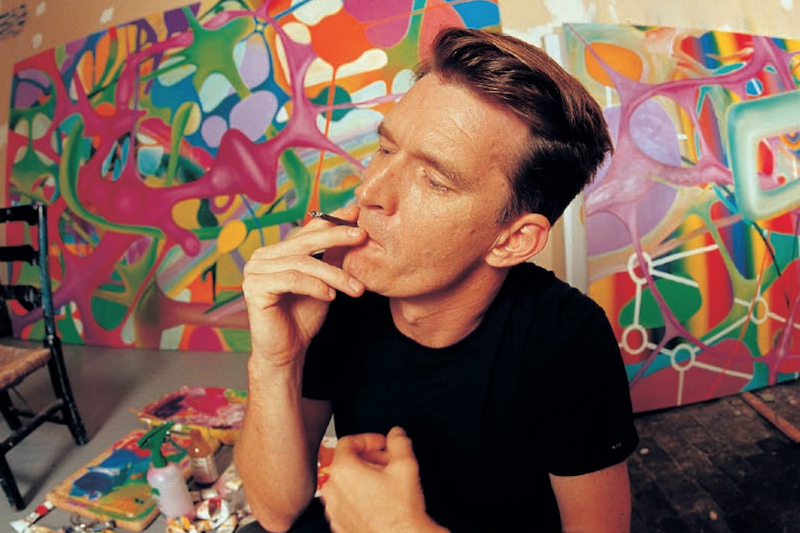

After a difficult start to his career, Matthys Gerber is now receiving critical acclaim.

Words: Andrew Frost

The end of an interview is often more fruitful than the start. After the biographical details have been recorded and the artist’s philosophy and views have been expressed, interviews often strike out into new ground – a free flowing discussion of connections and ideas. As I talk with Matthys Gerber in the offices of Sarah Cottier, his Sydney gallerist, I ask him about a photograph of Salvador Dalí that appears in Gerber’s artist book Mono Poly.

Although the photograph of the late Surrealist is an amusing inclusion in the grab bag of source images and reproductions of Gerber’s work, there are connections to the optical experiments and curlicues of Dalí’s restless work. Gerber’s answer is surprising. “The first exhibition that I saw that had a great impact on me was a Salvador Dalí exhibition in Rotterdam,” he recalls. “My grandmother took me to see it and it was then that I decided that I wanted to be an artist.”

For Gerber, the connection to Dalí has much to do with a refusal to follow the classic modernist role of the artist as tragic hero. “What I see in Dalí is the redundancy of the artist as ‘truth teller’,” says Gerber. “The thing that usually gets attributed to artists is the idea of being honest and humble. I think it was Dalí who said, because of Hollywood, art would never been the same. Like Marcel Duchamp’s work, you can never look at a single painting anymore, you have to know an artist’s entire oeuvre in order to understand their intention.” If there was ever an Australian artist who needed to be judged by his/her oeuvre rather than isolated examples of his/her work, it’s Matthys Gerber.

Born in 1956 in Delft in the Netherlands, Gerber arrived in Australia with his parents in 1972. After six years living in Denmark and eight in Holland, Gerber’s first few years in Australia were difficult.

What had started as a three year posting with Unilever for Gerber’s father turned into a permanent stay. For a 16-year-old with a European sensibility and upbringing, relocation to the antipodes was a shock. “We were supposed to go back after three years but we didn’t,” says Gerber. “My parents decided to stay. I hated it. I thought it was like living in Johannesburg. I wanted to go back but I couldn’t because of conscription in Holland. I was scared of that and kept postponing a return. It wasn’t until my trip to Europe in 1995 that I decided I preferred Australia and actually quite liked it.”

Gerber’s interests in the traditions of European conceptualism and classicism, and an exposure through his mother to philosophy lectures at Sydney University, put the artist at odds with the prevailing orthodoxy of the art world in Sydney in the late 1970s. “My interests were largely built on memories of having seen art prior to leaving Europe,” says Gerber. “I saw exhibitions of Pop Art, COBRA, Surrealism and lots of very dark, romantic images of older European art. When I came here there was a lack of that. The art world seemed to have started in the 1960s with primarily American influences.”

Although Gerber attempted to study art he abandoned two courses. “The 1970s were the age of Brett Whiteley and Robert Klippel and people like that, and it just wasn’t interesting to me, What I ended up doing was painting and attending lectures at Sydney University, sitting in on tutorials,” says Gerber. As a ring-in in the General Philosophy Department, Gerber was exposed to the teachings of Elizabeth Gross, and made connections with the emerging scene of young artists influenced by post modernism. “Liz Gross attracted a lot of people from the outside who were just sitting in on classes,” recalls Gerber, “the classes would be very full with 40 people attending. I still remember seeing people on the other side of the room, like artists Janet Burchill and Jennifer McCamley.”

In 1980, after having two works hung in the Archibald and Sulman Prize exhibitions in 1979, Gerber had his first solo exhibition at Hogarth Galleries in Sydney. Four years later he moved to Coventry Gallery. Although newspaper reviews from the period noted Gerber’s work, they seemed somewhat confused, reacting to the artist’s aesthetic choices as though they were “insincere” or “kitsch”.

In 1988 Gerber had his first exhibition with Mori Gallery in Sydney and, as he recalls, the emergent generation of conceptual painters offered a more sympathetic context for his art. Although other Sydney artists such as ADS Donaldson, Lindy Lee and John Young were working in similar areas to Gerber, conservative critics were hostile. While writers such as Catherine Lumby were attempt-ing to give a voice to the motivations and influences of these artists, the mainstream critical reception to Gerber’s work ranged from confusion to outright hostility. Typically, for an artist such as Gerber, these decade- old attitudes persist. “This kind of reaction is quite bewildering to me,” says Gerber, “I don’t see the difference between myself and a painter like Michael Johnson. It’s just paint-ing. I don’t understand why people think it’s cynical or ironically intended. In a different context, say in Europe or in New York, there might have been a dozen different people doing the same things as me – so it wouldn’t have been seen in the same way. Working this way is very much a solo activity. Even for people like Hany Armanious, it’s a solo activity. There is a very small group of people whose positions get lumbered with a lot of misjudgments.”

Gerber joined a number of his peers exhibiting at Yuill/Crowley gallery in the early 1990s and moved on to Sarah Cottier Gallery in 1996. Although the critical reaction to his work has grown kinder over the last few years and Gerber has enjoyed a sense of community with his fellow Sarah Cottier Gallery artists, his work has remained very much the result of a singular vision. Growing out of the school of 1980s conceptual painters, Gerber has set himself the project of examining the very language of creating images through painting. Although he questions the idea of “conceptual” painting – asking if any painting is not in some way conceptual – his work is a logical continuation of the challenges set down by artists such as Andy Warhol and Gerhard Richter, two artists Gerber cites throughout our interview. “I set myself the task of investigating painting by breaking it up into genres that are ready-made. Landscape, portraiture, text paintings – very much in the vein of Warhol or Richter,“ says Gerber. “I thought, how does one revisit certain genres within painting?”

Gerber’s work is about the negation of generic symbols in paint-ing, manipulating and playing with the signifiers of “landscape”, “portraiture” and “abstract” to create a hyperbolic, overloaded and “super-generic” version of these very same types of painting. Unsettling and unaccountably evocative, his works hover in an uncomfortable space between the familiar and the strange. “I wanted to get away from the direct appropriation of things and more towards dealing with the amateurishness of painting, looking at the debased qualities of it,” says Gerber. “Whenever anyone told me that you couldn’t look at something, that was when it intrigued me. The landscapes I did weren’t necessarily there because of their kitsch value, they were there because they were the synthesis of everything landscape painting hitherto had been,” he adds.

Although Gerber says the continuity of his seemingly disparate works is “organic” – art that ranges from abstracts to landscapes, Rorschach inkblots rendered in cut out, to cheesy images of Jesus Christ – he rejects the idea that the evolution from one series of works to the next is purely reactive.

Over the last few years, Gerber has embarked on a series of works that could be called “abstract”, although the conceptual rather than purely gestural basis of the paintings calls into question the easy categorization of his works into a given genre. Gerber’s work shifts between a fascination with the techniques of painting and what those techniques suggest. When talking about his landscapes, Gerber could well be describing his entire oeuvre. “Lacan said that the pleasure in the trompe l’oeil is the fact that you know you’re being cheated,” says Gerber. “It’s not the cheating as such, it’s the knowledge of how that is achieved technically that gives the pleasure. It’s the laying bare of the illusion that actually makes it not an illusion … ”

BUYING GERBER

Like many of his generation, Matthys Gerber’s works have found a home within collections of public galleries including the National Gallery of Australia, The Museum of Contemporary Art and The National Gallery of Victoria, as well as in the corporate holdings of Allen, Allen and Hemsley, News Ltd., and private collections in Europe and Australia. Through his gallery, Gerber’s work can be had from $3,000 up to $20,000. In the secondary market, Gerber has been a part of a growing market surge in con-temporary Australian art. His work 1560 (From Mother and Son), sold for $7,050 at a Christie’s sale in 2000 against an estimate of $4,500-$6,000. At the lower end of his secondary market sales, Gerber’s work can be had for around $1,500 and up. His work Science in the Wilderness from 1984 fetched $1,725 against an estimate of $1,500-3,000 at Sotheby’s in 1998.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 17, JUL – SEP 2001.