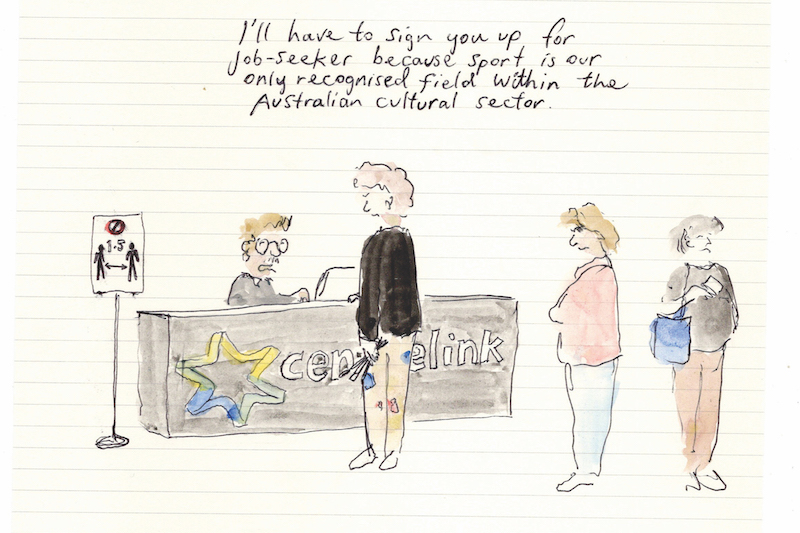

Money Sullies Art: Starving artists

In this expanded Money Sullies Art, we address the cultural expectations that frame the economic plight of artists today. Is there any lingering romance left in the concept of the starving artist? Does a modern artist still need to be a hero? Isn’t it all just theatre anyway? And when will we finally see a collapse of the concepts of the sanctity of art and the grubbiness of money?

Words: Andrew Frost, Michael Do, Carrie Miller, Tai Mitsuji

Illustrations: Coen Young

Art and Utility

When we think about the changing role of the artist, it’s worthwhile being reminded that even recently [relatively speaking] it was very different. Here’s an example.

One of the most popular English artists of the mid-19th century was the painter John Martin (1789-1854). He’s notable for a number of reasons, but he’s best remembered now as the creator of vast canvases that depicted grand scenes from the Old Testament as well as apocalyptic images of the end of the world. A trio of Martin’s paintings was toured as a large-scale theatrical presentation, an event that attracted more than 4 million people around the world, including in Australia.

Martin was so popular, and commercially successful, that he bought a country house, cultivated connections with patrons, English and European royalty, and paid for the legal defence of his brother Jonathan, who had attempted to burn down a church.

Meanwhile, Martin’s print works were being copied and sold without his permission, a tricky situation given the lack of copyright law in the 19th century, which he fought unsuccessfully to be stopped, although he did manage to put an unauthorised diorama version of one his paintings out of business.

Despite some setbacks, including a bout of depression and deaths in the family, Martin was able to indulge his other creative aspirations such as designing an efficient and modern sewage system for the English capital, and later, an interconnecting circular railway line that anticipated the eventual London underground system. Neither of his designs were actually used, but Martin had time on his hands, and his ultimate ambition was not to be an artist, but to be remembered as someone useful: an engineer.

The interesting part of this story is that Martin wasn’t born into wealth. His family lived in a one room house and it was only after an indentured apprenticeship as a coach painter fell through that young Martin ended up being apprenticed to an Italian-born artist in Northern England. From there, Martin’s aspiration was upwardly mobile, via one of the few paths available to young white men in the age, and that was as an artist.

Historically, artists were usually viewed as craftspeople. In the Middle Ages artists belonged to the same guild as builders and cooks. Art was therefore almost entirely a product of the patronage of the Church. It was only in the Renaissance period that artists and their work were elevated out of the working class into what would now be the equivalent of the middle class. The rich wanted art to adorn their walls and halls, and artist were paid handsomely to create it for them. This was also the period that established professional royally sponsored academies and their attached or associated art schools across Europe.

The role of the artist was thus established as someone who worked on creating art that featured morally educative subjects, illustrating notable historical events, Bible stories, and portraits of the noble and the good. This was the way people liked it, and most artists were happy.

The latter half of the 19th century was the era when the contemporary notion of the suffering artist really took root. With few and rare exceptions, artists of the late Romantic era tended to be the shiftless sons – and some daughters – of the middle class, or even wealthy aristocrats, slumming it as artists until they were either successful, died, or returned to the family business.

The attraction of the bohemian ideal is itself an historical aberration. One can reasonably argue that the period from the end of the 19th century until now has seen a shift away from the Van Gogh model of the saintly artist figure back towards something akin to the era of Martin. Which artist wouldn’t want to be successful, own a country estate and be served by apprentices and assistants while being patronised by the wealthy?

Actually, there is another role for the artist and that, interestingly, connects to Martin’s ambition to leave art behind for socially helpful work. There are of course artists who don’t want to make art that gets sold in galleries, but instead create relationships between people with creative thinking, and produce outcomes that have social applicability – be it improved, environmentally conscious farming techniques, ecologically sustainable cooking, or green design for cheap housing.

Is that art? Who cares? Martin would approve.

Andrew Frost

The artist as hero?

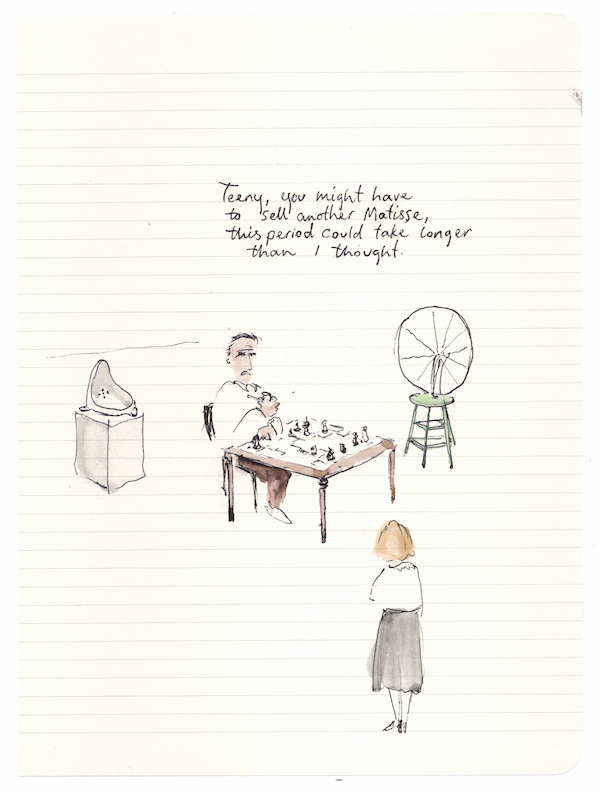

In 1891, Paul Gauguin set out for Tahiti. This was a single journey, yet the artist flirted with two very different accounts of it. In the opening sentences of his publicised travel journal, Noa Noa, we find the first version. There, Gauguin suggested the length and hardship of the trip – “a sixty-three days’ voyage, [with] sixty-three days of feverish expectancy” – invoking the rhetoric of the struggling, starving artist, who had weathered the storms of life. But Gauguin had contemplated another version of this text. Originally, the painter had thought to begin it with a not-so-subtle reference to a government letter, which had seen him travel in relative luxury. This bureaucratic missive had enabled the artist to sleep among the officers aboard the ship, rather than the common men. Standing at this literary crossroads, Gauguin opted for the drama of the starving artist, setting forth a theatrical precedent that has come to be (both intentionally and unknowingly) replicated time and time again, in the decades and century since.

One replicator is Takashi Murakami. The Japanese artist-designer-celebrity does not immediately spring to mind when we think about the archetype of the starving artist. Not only do his artworks sell for millions – in fact, he was commissioned to create the centrepiece of the recent exhibition Japan Supernatural at the Art Gallery of NSW – but Murakami’s work has also found a home in the broader cultural industries. Indeed, we do not have to look far before we spy his designs adorning Louis Vuitton bags, emblazoning Uniqlo apparel, and illustrating Kanye West album covers. Or put another way, the artist easily sits within the proverbial 1 per cent. His popularity and prosperity could not be farther from the likes of Vincent van Gogh (the artistic starver-in-chief), who only sold one painting during his lifetime. In fact, Murakami’s contemporary success is antithetical to our vision of the emaciated Dutchman, whose genius (we are continually told) was formed in the crucible of personal pain and struggle. Murakami’s name is more comfortably uttered in the same breath as Damien Hirst’s or Jeff Koons’, artists who permanently sit at the intersection between contemporary art and unspeakable sums of money. So why am I still talking about him? And how could Murakami claim any ties to the starving artist? Well, unlike Gauguin, Murakami does not sleep with the ship’s officers.

Despite his wealth, Murakami has been able to self-style as something of an ascetic. Economist and art market analyst Don Thompson notes that “[Murakami] promotes the myth that he spends every night in a sleeping bag on his studio floor, rather than, say, in his Upper East Side Manhattan town home.” In a 2005 profile in The New York Times Magazine, curator and museum director Dana Friis-Hansen seemed to confirm this, observing how Murakami “usually…. sleep[s] in the gallery while he is setting up. He’ll bring assistants and sleeping bags, and they’ll cook noodles there.”

According to Friis-Hansen, this leaves Murakami in a state of existential duality: “He makes art and sleeps”. Hearing such words, the great divide that previously separated Murakami from van Gogh almost melts away, or, at least, feels traversable. In an Instagram post from September 26, 2017, Murakami published a photo of himself cocooned in a bright orange sleeping bag, lying atop the plush white linen of a hotel bed. It is undoubtedly an odd image; a contradiction in terms. Yet this oddity plays a critical role in reframing Murakami, as it connects him to the legacies of the outsider artist, even as he sleeps inside the luxury hotel.

But is this just theatre? Are the sleeping bags on the gallery floor carefully orchestrated marketing props? Is this the calculated act of a cultural insider? Or, is Murakami’s sleeping arrangement and singular focus genuine? Does some ineffable force anchor him within the studio, refusing the temptations of the outside world? It doesn’t really matter. Whether artificial or otherwise, the image of Murakami in a sleeping bag suggests the immutable cultural capital that the starving artist still holds. Even for the contemporary artist, the standard of the heroic Modernist outsider remains. No matter the circumstance, they must always sleep among the crew.

Tai Mitsuji

Artists, class and performative bohemia

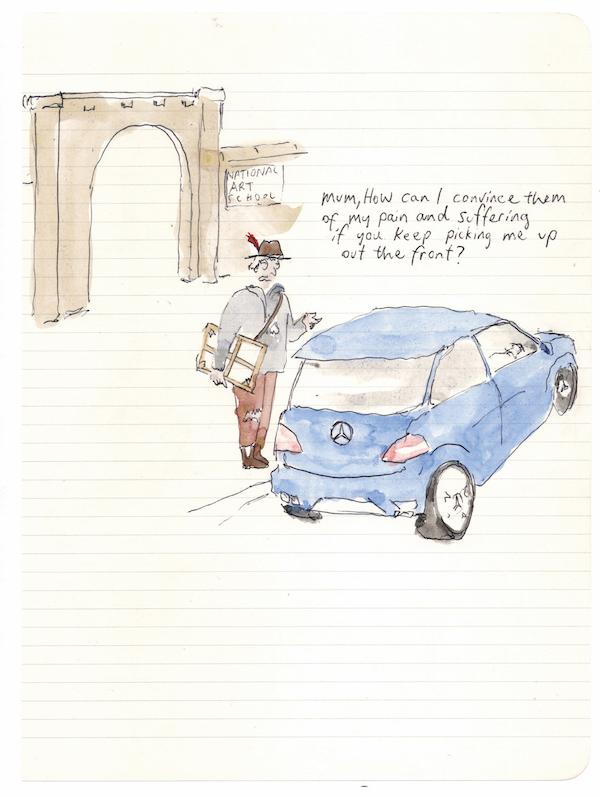

The modern romantic notion of the starving artist was once the embodiment of principled impoverishment. Being seen to sacrifice material comfort in the noble pursuit of a life of the mind was considered the highest form of self-actualisation. These days, the baller mentality of the average teenager makes the nobility of poverty seem as quaint a notion as the idea that people should only hold US Presidential Office if they have a deep respect for democratic norms.

So, where does that leave younger artists who have been born into a corporate culture not of their own making, that’s characterised by a neoliberal world that views financial security as the fundamental pre-condition of human existence? Given this cultural reality, is it possible, even desirable, to eschew a comfortable life in order to pursue the life of the artist? Is there any residual romance left in the concept of the starving artist today?

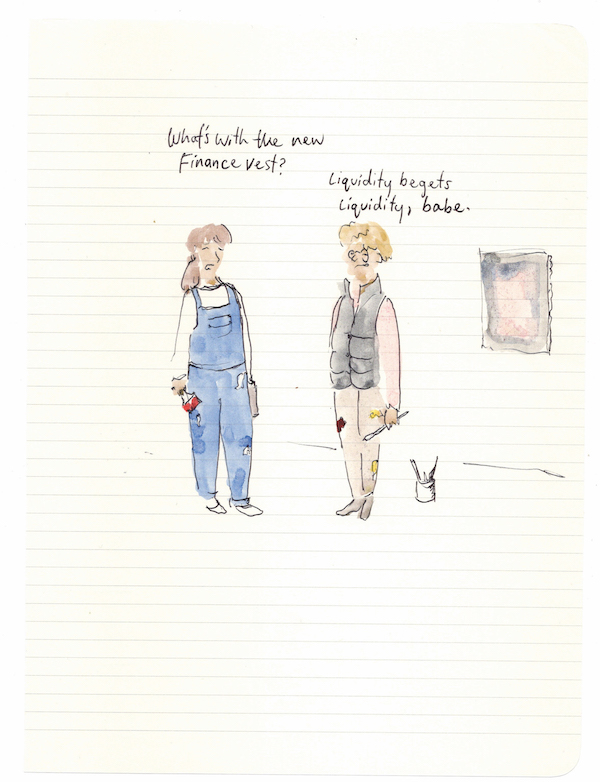

There are a number of social, economic, and political factors at play here. It’s hard for the cultural working class to remain a bunch of purists in the context of urban gentrification, where old warehouses have been converted into New York-style apartments. If you want to make it as an artist these days, you need to get your hustle on to even afford a tiny space to set up your oversized Mac and make video work. This sense of hustle can come across as brash confidence in the economic worth of unproven talent – the opposite of the bohemian approach to art and life. But the fact that artists now pay the equivalent of a house down payment just to go to art school means they kind of have to show blind faith in what they do and be able to attach an economic value to it.

Perpetuating the starving artist myth really only serves older artists well now, particularly ones who felt they didn’t get the recognition they deserved back in the

good old days. You will see them at biennales – full of resentment, self-pity, and warm wine – reminiscing about when artists were true bohemians, sacrificing contentment for the lifelong struggle of a higher pursuit. On the other hand, when there’s more capacity than ever to aspire to, and accumulate, stuff, perhaps there’s more to sacrifice. Aspirational culture infects everyone – it’s only the most privileged who want to divest themselves of material possessions, live in tiny houses, and make their own soap. And what was so hard about giving up a shitty suburban life back in the 1950s and 1960s when boomers were doing it, when there weren’t opportunities to make a career and some serious cash out of the art business, and the most you could hope for was a job in a bank, or being married to that guy.

I remember someone telling me at the exhibition opening of a celebrated Australian painter, that he splashed his pants with paint drips to look like he had absent-mindedly walked into the gallery straight from a hard day in the studio. This anecdote is a reminder that the starving artist persona has always had a performative aspect to it – it’s always been more about public perception than private psychological motivation. Our ideas about artists are necessarily divorced from the lived reality of individual artists lives; those material facts just get in the way of the grand narratives we like to tell about great individuals whose genius transcends the banal demands of ordinary life.

Now that almost everyone dresses ironically – even facial hair seems to be some kind of intellectual statement – it’s no longer possible to distinguish between a starving artist and a successful one who just dresses like a hobo for dramatic effect anyway.

Carrie Miller

A way forward: Lessons offered by relational aesthetics and Covid-19 rescue packages

Over the past half-century, the visual arts has undergone an exceptional transformation, with the public, private and commercial art spheres booming with greater ambition. Underwritten by the availability of capital and connectivity, visual art has never been so available to collectors, accessible to appreciators and outward-looking in its approach, enveloping a range of cultural references, societal movements and technologies. These circumstances have birthed generations of artists who now work in contexts far removed from the solitary, tortured artist-as-martyr-madman-shaman conceptions that once prevailed. In order to earn their living, artists today rely on a complex ecosystem of support structures that include public and private grants, prizes, galleries, commercial opportunities and private philanthropy.

Their careers tend to be guided by amorphous and transient opportunities that are contingent on timing and circumstance. In navigating this reality, artists must rely on their entrepreneurial skills to move and work across different projects, events and galleries. These working conditions are further compounded by a financial insecurity, the lack of discernible career structures, trade unions and the social benefits that other industries take for granted such as fringe benefits. This precarity has made the sudden fall brought on by coronavirus much more painful for artists. Every aspect of the art world, from the mightiest museums to the most recent art school grads, has been devastated by the pandemic lockdown, with the economic futures of the sector left uncertain.

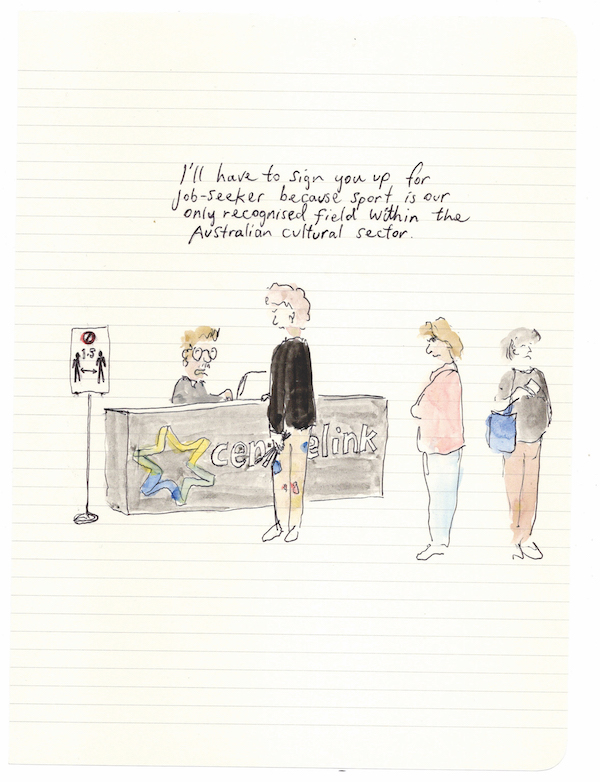

While an economics of solidarity is finally emerging, with private foundations and state and federal government supporting Australian artists, these opportunities are nonetheless coloured by the limited view of how Western societies understand visual art and capital. There is a dissonance between the cultural value and the capital value of artists. This is in part explained by the difficulty in quantifying artistic labour, which is often intangible and exists independent from formal markets where prices can be easily determined (say a slice of banana bread from your local cafe or perhaps a gold bullion bar).

In grappling with this tension, artists have developed strategies to challenge the ever-accelerating cycles of consumption and obsolesce in the Western world; conceiving of an art world disconnected from the capitalist systems of exchange that force artists to work and exist so precariously. For example, French curator Nicolas Bourriaud observed a generation of artists in the 1990s who drew upon strategies of institutional critique from the 1960s and 1970s, whereby artists disappeared the art object in favour for art works and ideas that resist commodification. This movement, which he titled Relational Aesthetics, reframed audiences as a collective social entity capable of temporary utopian encounters.

Artists like Liam Gillick, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Christine Hill and Vanessa Beecroft created contexts where audiences could resist the intensely commodified, transactional and virtual relationships heralded by Globalisation. These gatherings, which Bourriaud called “microtopias”, were opportunities for audiences to pause and inhabit the world in a different way. The artist was the designer of social interactions, co-opting their audience through different prompts to create art gatherings disconnected from the typical acts of purchasing, contracting and schmoozing that typically take place.

This historical movement is an example of artist-led cultural reform that emphasises human care and empathy above economic interests. While critics like English historian Claire Bishop have criticised Relational Aesthetics as a toothless naïve exercise, the movement’s idealism is critical in reconciling the role of artists, and to understanding how and why our era of hyper-capitalism has let them down. These relational encounters offer us a loose template for care and consideration that will guide us through this crisis. After all, without imaginary ideals like this, there is no possibility of a radical reimagination of this status quo.

The COVID-19 pandemic has foregrounded the wealth inequalities in all industries. In the case of the cultural sector, vulnerable arts organisations, arts workers, and artists are clamouring for answers. And in this uncertainty, the pandemic offers the potential for action and leadership. This time calls for a recommitment to artists, resetting our all-pervasive economic rationalism in favour of a system of open-ended concern for human wellbeing and quality of life — expanding Bourriaud’s concept of a microtopia into a macrotopia.

Such a system could include reduced working hours to ensure artists are better able to devote time to their practice in lieu of their day jobs, basic income guarantees, or a reorientation of existing state provisions that better compensate artistic practice – an extension of the economics of solidarity that has been partially put in place by the Australian State and Federal governments to tide furloughed or laid-off workers during the lockdown. Such measures would recognise the social value of creative endeavours, better protecting and supporting artists who are the creative backbone of the country. Artists do not act in isolation; much like anyone else, they affect and are affected by government and business decisions.

A new paradigm that redresses this precarity would also require the distinctions between the sanctity of art and the grubbiness of money to be collapsed. We must abandon prejudices against artists open to commercialism who are often vilified as sell outs. This system would also need to rewrite the idea that artists can be paid in exposure and opportunity instead of money for their time and labour. With this in mind, I have suggested propositions for contemplation and action while we rally together during the pandemic and consider how we can reset economic, social and historical relationships to build a society that we want. Only in this way, can we finally begin to recognise and then resolve the precarity of artists which has been for too long ignored and dismissed as simply a necessary condition of art making.

Micheal Do