Natasha Bieniek: Natural Magnetism

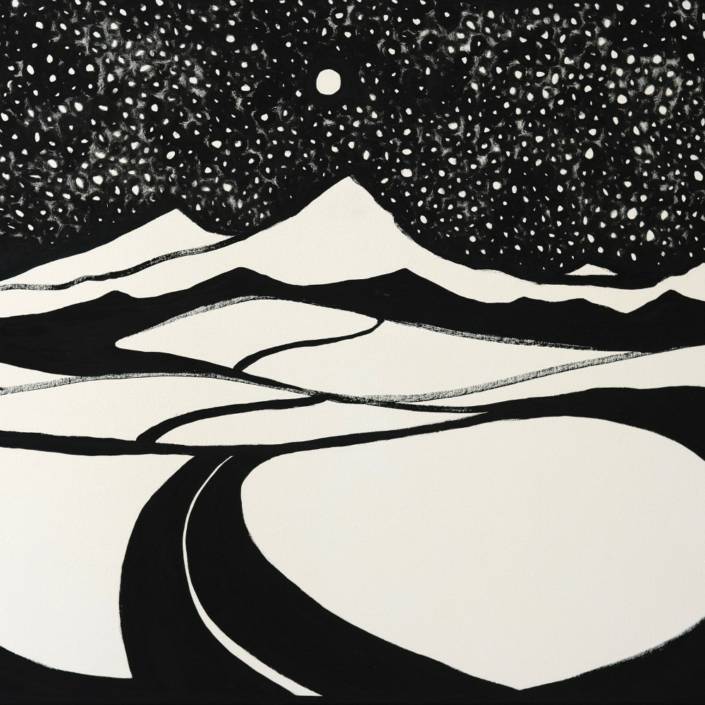

Attuned to the natural world, Natasha Bieniek relays the minutia of the outdoors in her paintings.

Words: Jo Higgins

Photography: Kirstin Gollings

It would seem, for Natasha Bieniek at least, that from little things big things do indeed grow because the Melbourne-based painter’s exquisitely detailed miniatures have been receiving some significant attention lately. In July last year Bieniek’s Polaroid-sized landscape painting Biophilia won the prestigious Wynne Prize. Several months later in September, her self-portrait Sahara received the $30,000 Portia Geach Memorial Award. This year she has been a finalist in no less than the Fleurieu Art Prize for her landscape Kumiko and the Archibald Prize, for her captivating portrait of Wendy Whiteley.

Bieniek is well-known as a portraitist but her latest exhibition, Bloombox at Jan Murphy Gallery in Brisbane, continues her exploration of those ideas she first encountered while painting the Biophilia series last year. In particular, she is drawn to biologist Edward Wilson’s suggestion that our tendency to affiliate with nature is an inherent and deeply rooted part of our biology. Says Bieniek, “I’ve been thinking a lot about how we relate to nature within an urban or inner-city context. I’ve noticed that we seem to instinctively compensate for a lack of window or view by introducing plants into otherwise sterile environments. We also very rarely question why we bring flowers into a hospital, pay more for hotels that overlook water and universally have a preference towards natural landscapes over cityscapes for example. I find this seemingly innate attraction to nature intriguing and I’m interested in exploring the role of nature in an otherwise industrialised and technologically advanced society.”

For the last two years Bieniek has been exploring the gardens close to Melbourne’s CBD, in part to escape the noise and chaos that surrounds her studio in Southbank, as multiple high-rise developments emerge around her. “I like the fact that within minutes my physical surroundings can shift so rapidly. It can be quite an immersive experience.”

For this series of ten paintings, Bieniek sought out a range of environments that reflected great biodiversity, interesting foliage and textures and a range of colours and tones. Most feature water, which Bieniek believes creates a sense of calm, and as a process, each painting tended to inform the next. “If I’ve created a work that contains a lot of muted tones, which is typically not beautiful, the next painting might have more brightness and electricity to it. My intention is depict a wide range of environments that encompass diverse sentiments and moods.”

Bieniek’s labour intensive, densely detailed, delicate paintings are composed from hundreds of photographs taken over several hours, following the sun through the gardens. They are then meticulously painted onto squares of dibond aluminium with thin layers of oil paint. “Although my work is traditional in technique, I have a strong correlation with modern working methods. I don’t necessarily see photography or computers as the opponents of painting, but rather vehicles to enhance painting and keep it moving forward.” These seamless shifts between technology and tradition, chaos and calm reflect Bieniek’s fascination with the complex interplay between people and nature. “I’m interested in the notion that a stronger connection with nature could enable us to further thrive as a species and foster a more satisfying existence.” Her tiny masterpieces offer a small and intimate glimpse at what might be possible.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 78, OCT-DEC 2016