Simon Denny: Game over

Simon Denny’s major new exhibition may seem like fun and games, but IRL the stakes are real, and the endgame has potentially catastrophic consequences for all players.

Words: Camilla Wagstaff

I’m standing in the darkened depths of a cavern carved from stone. In the corner of this vast and imposing space, a King Island Brown Thornbill twitters restlessly in a bright white cage. Of course, it’s not a real Thornbill – a bird whose numbers have been so decimated by human activity its extinction is essentially imminent. I watch this particular bird through a device enhanced with augmented reality hanging around my neck. I listen to its call – a call never reproduced until now – from headphones nestled snugly around my ears.

Indeed, my “canary in the coalmine” is the opening moment of New Zealand artist Simon Denny’s Mine, debuting this week in the underground spaces of Hobart’s Museum of Old and New art (MONA).

Denny is an interrogator of systems – systems of technology, of power, of control – and now systems of resource and data extraction (which, in effect, are systems of technology, power and control). In Mine, he draws together the profound parallels between literally taking things out of the earth and the ways we now capture the data of human practices. He forces us to dig deep and think about extraction as a kind of co-dependant, three-way relationship between labour, resources and the immense amounts of data at our disposal today.

“I wanted to look at the relationships between human and non-human, worker and non-worker,” Denny tells me. “What are these relational systems that keep us bound together in social contracts around production? What are these systems doing to us?”

There’s a lovely poetry between the exhibition’s theme and the space in which it’s staged. In fact, Denny couldn’t really imagine the show being anywhere else. “The museum of course is literally a hole in the ground,” he says. “But it also runs on The O [an iPod device that helps viewers navigate MONA], as a very important part of filtering the experience of the museum.”

The O device has been guiding visitors through MONA for years now as a replacement for physical wall texts and human tour guides. “While it gives you information, it also takes engagement data while you’re a viewer in the museum,” notes Denny. “So, in a way, we’re in a mineshaft of a museum, but we’re also in a data mining business at the same time.”

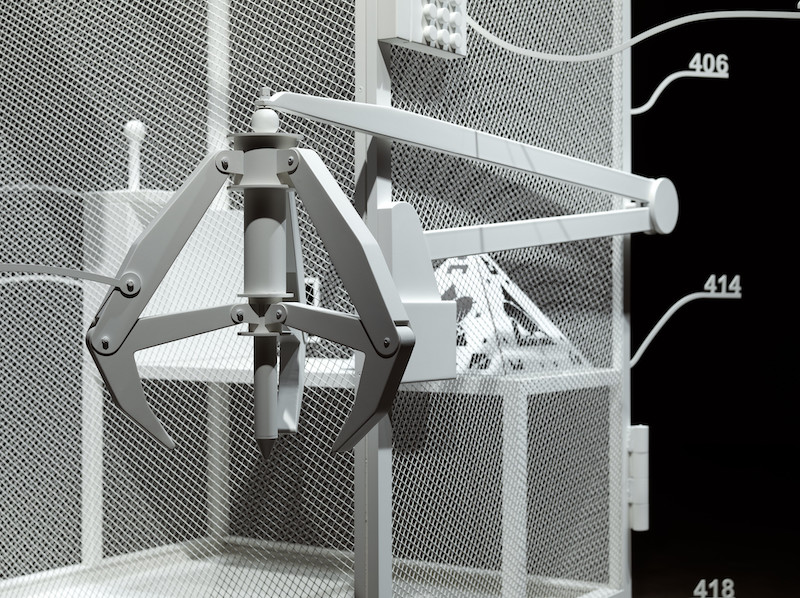

The room with the cage (initially patented by Amazon for humans to work among robots), opens out into a brightly-lit, human-sized board game replete with garish gridded squares and imposing cardboard mining machines. The game is based on Squatter, a 1960s game centred on the dynamics of sheep farming. In Denny’s version – he calls it Extractor – you’re mining and monetising data in place of farming sheep.

The significance of the gaming set up is not lost here. In fact, by forcing visitors to interact so heavily with the show – by literally placing us as players on a board – we become acutely aware of our complicity in extraction systems: we are at once the extractors and the extracted. More than this, we become viscerally aware of how off the board, we are collectively hurtling towards an endgame with catastrophic consequences for all players.

Indeed, Mine ultimately highlights a global “canary in the coal mine” moment, how real the stakes have become, and how close we are to game over. In the context of mining, a canary gives its life to alert humans of an unhealthy, unsustainable environment. In a similar way, the massive changes in climate and biodiversity we’re experiencing today – grounded here in the Thornbill’s virtual presence – speak to the increasing unsustainability of our modern world. “We are exhausting the resources of the planet,” Denny says simply. “We need to start thinking about things in a different way.”

The catalogue for the show is itself a regular-sized version of Extractor, complete with critical essays (and “other surprises”, as Denny puts it). He sees the catalogue as a chance for visitors to further think about their place within extraction, unpacking and processing the connections between older types of industries like resource mining and newer types of industries like data mining. “They can seem very far apart; when you’re using Facebook, you’re not thinking of rocks in the ground,” says Denny. “But it’s all part of an interconnected system, an old system, an industrial system, that I think needs to change.”

Simon Denny’s Mine shows at MONA, Hobart, until 13 April 2020. Mine is curated by MONA’s Jarrod Rawlins and Emma Pike.

Denny is represented by Fine Arts, Sydney in Australia; Michael Lett in New Zealand; Petzel Gallery and Altman Siegel in the USA; Galerie Buchholz in Germany; and T293 in Italy.

Header image: Simon Denny standing in his Exhibition Mine, Mona, 2019. Photo: Camilla Wagstaff.

Body images: Installation views of Simon Denny’s Exhibition Mine, Mona, 2019. Photo: Jesse Hunniford. Courtesy: MONA, Hobart.