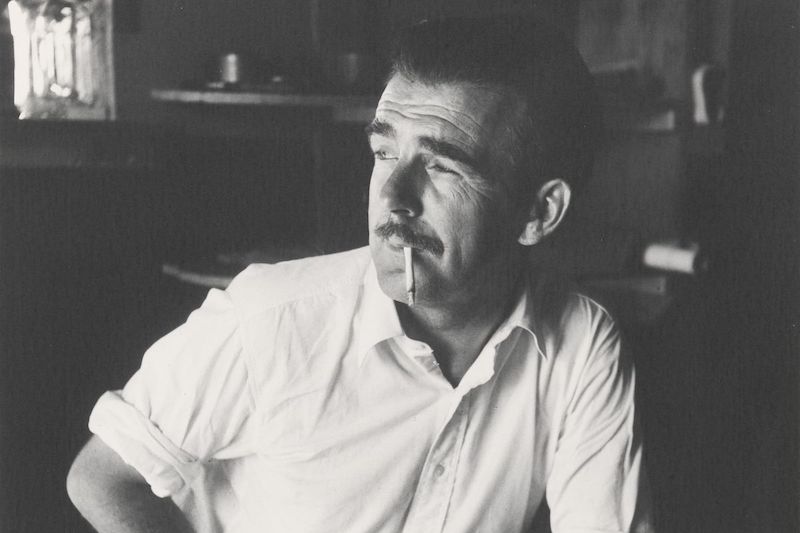

William Dobell: Yours Sincerely

Judith White profiles the life and art of one of Australia’s most prolific, controversial and admired painters…

Words: Judith White

BIOGRAPHY

Sir William Dobell is best known as the finest and most controversial portrait painter of his generation, his name forever associated with the court case which ensued when his Portrait of an Artist (Joshua Smith) won the 1943 Archibald Prize. He was in fact a complex, versatile artist whose great strengths were his mastery of traditional draughtsmanship and his dissecting eye.

Born in Newcastle in 1899, the seventh child of a bricklayer, he was one of the few successful artists of his times to come from an entirely working class background. At Cooks Hill Public School he excelled at nothing but drawing. In those days the city had no art gallery, and one of his early inspirations was a pencil drawing of George Stephenson’s famous engine The Rocket, which was the proud possession of his engine-driver grandfather.

Dobell left school at 14, working at what jobs he could find – his first was as a ‘dog-walloper’, keeping animals away from the bolts of cloth outside a draper’s shop – and attending drawing classes at night. In 1916 he became article to an architect, which enabled him to pursue draughtsmanship. Eight years later he moved to Sydney, as a draughtsman for Wunderlich Ltd in Redfern, manufacturers of ironwork and terracotta, then to its advertising office. It was now, at the age of 25, that he finally enrolled as an art student, attending the Julian Ashton School at same time as John Passmore. It was a time when the artist George Lambert, who taught there, encouraged a ‘safe’ version of modernism, within the traditions of the Royal Academy – as did Sydney Ure Smith, the influential editor of Art in Australia, soon to become a supporter of the young Dobell.

In 1929 came his first modest success, when his painting of dancers After the Matinee won third prize in the Australian Art Quest at the newly-opened State Theatre in Sydney. Soon afterwards, a seated male nude won him the Society of Artists Travelling Scholarship. He embarked for London at the age of 30.

Europe was a revelation. For the first time, Dobell could see original works of significance. He enrolled at the Slade, learning rapidly and taking first prize for figure painting in 1930 with his Nude Study. In the same year he visited Holland, and fell in love with the work of Rembrandt. He soon left the Slade to concentrate on sketching in the streets of London and the surrounding countryside, and painting in a studio he shared with fellow expatriate, Passmore.

Dobell spent almost a decade in London, the years of the Great Depression. He was living on five pounds a week, staying in seedy bedsits in Pimlico and Bayswater, and as time went on he was obliged to supplement his income in various ways. He worked as a film extra and in 1936-7 joined Arthur Murch and a bunch of Australian artists to decorate the Wool Pavilion for the great Glasgow Fair. But all the time he drew and painted the life he saw around him.

Fellow artist James Gleeson, writing of these years in his book on Dobell, comments perceptively: “He sees the ordinary and paints it as though it was extraordinary; he sees the commonplace and paints it as though it was unique; he sees the ugly and paints it as though it was beautiful. It is a characteristic he shares with Rembrandt.”

As the Depression wore on he developed a satirical edge. His 1937 painting Mrs South Kensington epitomised a bitter, desiccated and ageing upper class. By contrast he depicted figures such as The Charlady and Street Singer with infinite compassion. The world he drew was almost Dickensian. In 1936 a sudden death at his lodgings inspired one of his most extraordinary works of the time, Dead Landlord: the bloated, ghostly figure of the deceased lies on the bed while his wife, turning away, begins to brush her hair. The incident, in which the woman told Dobell they would have the street’s first ham funeral, would later become the starting point for Patrick White’s play The Ham Funeral.

In 1938, with war imminent and his father dying, he returned to Australia. Modern painting was finally being shown here: in 1938 the Contemporary Art Society was formed in Melbourne, and Sir Keith Murdoch was sponsoring Australia’s first great exhibitions of modernism. Dobell taught at East Sydney Technical College (now the National Art School), then joined the war effort, first as a camouflage painter, then as a war artist, producing a series of striking genre pictures of people at work.

At the same time, from his home base in Kings Cross, he painted a series of striking portraits: in 1940 The Cypriot, in 1941 The Strapper, in 1943 The Billy Boy and Brian Penton. Each time, with great versatility, he adjusted his technique to the personality of the sitter. His famous portrait of Joshua Smith, with whom he had shared a tent when both were camouflage painters, was closer to expressionism than any of them. When it won the Archibald it unleashed a storm.

In a distressing episode, Smith’s parents turned up on Dobell’s doorstep early one morning to try to suppress the painting. But the main attack was led by the conservatives of the Sydney art world, who dubbed it a caricature.

The artist was deluged with portrait commissions, and he was not short of public defenders. Extraordinary as it may now seem, one bastion of support was the Daily Telegraph, then owned by Sir Frank Packer who was partial to a Dobell himself. “If William Dobell were a hack painter,” thundered one editorial, “he could win six Archibald Prizes without wringing one howl from the studio mediocrities. His crimes are: real talent and visual imagination.”

Two weeks after the announcement the ABC invited Dobell to be its radio talk Guest of Honour. He acquitted himself well, explaining: “You might say I am trying to create something instead of copying something, when I set out to paint a portrait. To me, a sincere artist is not one who makes a faithful attempt to put on a canvas what is in front of him, but one who tries to create something which is a living thing in itself, regardless of the subject.”

But the following year the court case brought by opponents of the decision took a severe toll on his nerves. Distinguished curators and critics gave evidence for him, and the case was thrown out, but being variously lionised and abused for almost two years had been an ordeal. Although he had many warm friendships Dobell was an intensely private man. After the hearing he became ill with severe dermatitis, and did not paint for a year.

His own evidence, however, is revealing of his philosophy. He did not, he told the court, regard himself as a modernist: the case was about the nature of art itself. “Leave the art out for the moment,” demanded counsel for the plaintiffs, Garfield Barwick. “You cannot leave art out,” was Dobell’s rapid rejoinder; and he never did.

Late in 1944 he retreated to Wangi Wangi, on the shores of Lake Macquarie, where his father had long since established a little holiday home. His sister Alice nursed him back to health, and by late 1945 the landscape had so engaged him that he was busy with his sketchpad once more. Wangi would remain his home for the rest of his life.

He tended to shun the bright lights of Sydney, resigning in 1947 from the Board of Trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales after four years. Hal Missingham later said that Dobell had to get “full as a boot” to face meetings, and his fellow Trustees rejected his recommendation to purchase a Donald Friend so often that he bought it himself. And the artist’s view of the celebrity portrait circuit can be judged from what he privately opined when commissioned to paint the Governor, Lord Wakehurst: “I’ll paint him like he really is: a blue-arsed monkey in a zoo!”

But in 1948 he won the Archibald for a second time, with his portrait of Margaret Olley, and he also took out the Wynne Prize for landscape, with Storm Approaching Wangi. In 1949 he visited New Guinea twice (Qantas sponsored a return trip), renewing his fascination with colour and producing memorable paintings such as Kanana and The Thatchers.

The 1950s brought friendship with Patrick White, a superb por-trait of Dame Mary Gilmore (“Dobell has put my ancestry into it,”she said with wonder), and another of Helena Rubinstein, whichwon the Australian Women’s Weekly portrait prize and was repro-duced in the two million circulation magazine. Both the Gilmoreand the Rubinstein represented a further development of theexpressionist tendency seen in the earlier Joshua Smith painting. In 1960 the artist was commissioned to produce a series of coverportraits for Time magazine. They included one of Sir RobertMenzies, who had opined at the time of the Archibald case that hewould be happy to be painted by Dobell, but in the event foundthe portrait so unflattering that he refused the gift of it from thepublishers.

The critics were always divided about Dobell. Even influential Sydney Morning Herald critic Paul Haefliger, a witness for himin the court case, once wrote of the “limited base” of his art.When in 1960 Dobell won his third Archibald with a portrait of Dr MacMahon, a young upstart by the name of Robert Hughes wrote: “Too little remains of the compelling character insight, the dissec-tion of a personality, that made Dobell the best romanticportraitist not only in Australia, but perhaps the world. Instead we have the exterior shell of his art.”

But back at Wangi the artist continued to work inventively. In turn he nursed his sister through her last years, but the late 1960s, when he lived there on his own with his dogs, drawing and paint-ing local figures and abstracts, were tranquil. He remained unfailingly conscientious in his work. “I am always worried whether I am doing my best work,” he told James Gleeson. At the local pub he was known simply as Bill. He accepted his knight-hood in 1965, he said, only “to get quits with the snobs”.

In 1969 he celebrated his 70th birthday. The following year Newcastle Art Gallery organised a major exhibition of his work. He was intensely proud that the Gallery named a Dobell Room for him, and the show was well received, with Elwyn Lynn writing in The Bulletin: “He is taking more risks than ever and if his theme is the uncertainty of life and its appearance there is nothing uncerin tain about his recent achievements.”

A month later, Dobell was dead. By the terms of his will, his entire estate, including his extensive private collection, went to benefit and promote art in Australia, and has been administered ever since by the Dobell Foundation.

The people of Wangi Wangi formed a committee to maintain his house and studio as a museum, and in October 1999 the property was given National Heritage status. In death Bill Dobell kept faith with the people from whom he had sprung; and they with him.

THE BEST WORKS AND WHERE TO FIND THEM

Dobell himself rarely pronounced about his works, but he is on record as saying that of the portraits Dame Mary Gilmore was “one of the best”. It is now at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Other works there include one of his best early paintings Boy at the Basin 1932, Self Portraits of 1932, 1937 and the 1940s, The Speakers, Hyde Park 1934, Sleeping Greek 1936, Mrs South Kensington 1937, Street Scene, Pimlico 1937, Saddle-My-Nag 1941 and the famous portraits Margaret Olley 1948 and Sir Robert Menzies 1960. The Gallery also has more than 1,000 studies, drawings and gouaches, the gift of the Dobell Foundation.

The Newcastle Region Art Gallery has the prize-winning Slade Nude 1930, the wonderful 1941 portrait The Strapper and a number of other works including Boy with a Bow 1953 and a portrait of Tunku Abdul Rahman 1963.

Another very fine portrait, of the legendary philosophy teacher Professor John Anderson 1962, is in the collection of the University of Sydney.

In the National Gallery of Australia are Billy Frost 1932, Regent’s Park 1936, The Red Lady 1937, The Thatchers 1953 (perhaps the most brilliant product of his visits to New Guinea), and his Sydney restaurateur portrait Chez Walter 1945.

Also in Canberra, the Australian War Memorial has some of the best of Dobell’s wartime work, including The Billy Boy 1943, Knocking-Off Time, Bankstown Aerodrome 1944 and his Sydney Graving Dock paintings of workers.

His haunting London painting Street Singer 1938 is in the Art Gallery of Western Australia, the Queensland Art Gallery has London Bridge 1936 and The Cypriot 1940 and the National Gallery of Victoria has Kensington Gardens 1935.

Some of the best works of the Sydney and Wangi years went to private collections. Sir Frank Packer bought Brian Penton 1943, Woman in a Hamburger 1944, Boy in a White Lap Lap 1952, and the Portrait of Helena Rubinstein 1957, which won his magazine prize.

The Joshua Smith portrait, bought by Sir Edward Hayward in 1949, was resold in 1998. Other notable private collectors have included Michael Gleeson-White, the Murdoch family, James Fairfax, the Lloyd Jones family and the Clune family.

PRICES AT AUCTION

In 1973 the Dobell Foundation sold a large number of works, using the funds to continue benefiting and promoting art. These days the sale of a major painting is something of an event. But Dobell was prolific, and during the 45 years of his artistic career a large number of works went into private collections and still change hands from time to time.

Record prices have been paid in recent years for portraits of unknown male figures. The highest was paid just over a year ago, in August 1998, for Wangi Boy – $497,500 at Christie’s in Sydney. The second highest, $332,500, was for Boy in Jodhpurs in 1996. In the past decade three other works have sold at more than $200,000.

The more valuable portraits will rarely come on the market, either because they are in public galleries or because they are in wealthy private collections. It is notable, though, that the famous 1943 Portrait of an Artist (Joshua Smith) sold as recently as 1998, for $222,500. The average price of a work in oils is something over $43,000.

There is more likely to be a steady trickle of drawings on the market. These sell on average at between $4,000 and $5,000, though the 1943 Study of Joshua Smith sold for $66,300 and a study for Boy at Basin for $46,000. Given Dobell’s superb draughtsmanship and prolific output of drawings, there are still gems to be found in this area of the market.

HOW TO START COLLECTING

Fortunately for the aspiring collector, the profusion of works in public galleries makes it easy to study his work, an essential first step in becoming familiar with his oeuvre. There are also some excellent published sources, including James Gleeson’s sympathetic, revealing biography William Dobell (Thames & Hudson 1964); Portrait of an Artist: A Biography of William Dobell by Brian Adams (Hutchinson Australia 1983) and Virginia Freeman’s Dobell on Dobell (Ure Smith 1970), consisting of interviews conducted near the end of the artist’s life. Once you are well informed about the body of work, watch out for Dobells in auction house catalogues and reputable commercial galleries.

This article was originally published in Art Collector issue 12, APR-JUN 2000.